Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica, often nicknamed the “Doomsday Glacier,” holds enough ice to raise global sea levels by about 65 centimeters, roughly two feet, if it were to collapse completely. That kind of rise would not just redraw coastlines on maps; it would show up in flooded subway stations, higher storm tides, and more frequent nuisance flooding in coastal cities.

A new international study led by Debangshu Banerjee at the University of Manitoba’s Centre for Earth Observation Science finds that a key part of Thwaites is breaking apart from the inside faster than scientists expected. Instead of melting from below being the main problem, the work shows that growing cracks in a fragile strip of ice are loosening the glacier’s grip on the seafloor and speeding up its slide toward the ocean.

Why the Thwaites Glacier matters for sea level

Thwaites is the widest glacier on Earth and is part of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, a region that is already losing ice at an increasing rate. Because so much of this ice sits on bedrock below sea level, it is especially vulnerable to warm ocean water that can creep in and thin it from underneath.

Right now, floating ledges of ice called ice shelves act like brakes on the glacier behind them, a bit like a cork in a bottle. If those shelves weaken or break, more land-based ice can flow into the ocean, adding to sea level rise that already shows up in higher insurance costs and bigger repair bills after coastal storms.

The International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration, a joint effort between U.S. and U.K. scientists, has warned that continued retreat of Thwaites and nearby ice could eventually lead to several meters of global sea level rise over the coming centuries. Experts stress that this would not happen overnight, but they also note that choices made this century will help decide how fast that future unfolds.

A 20‑year record of cracks and movement

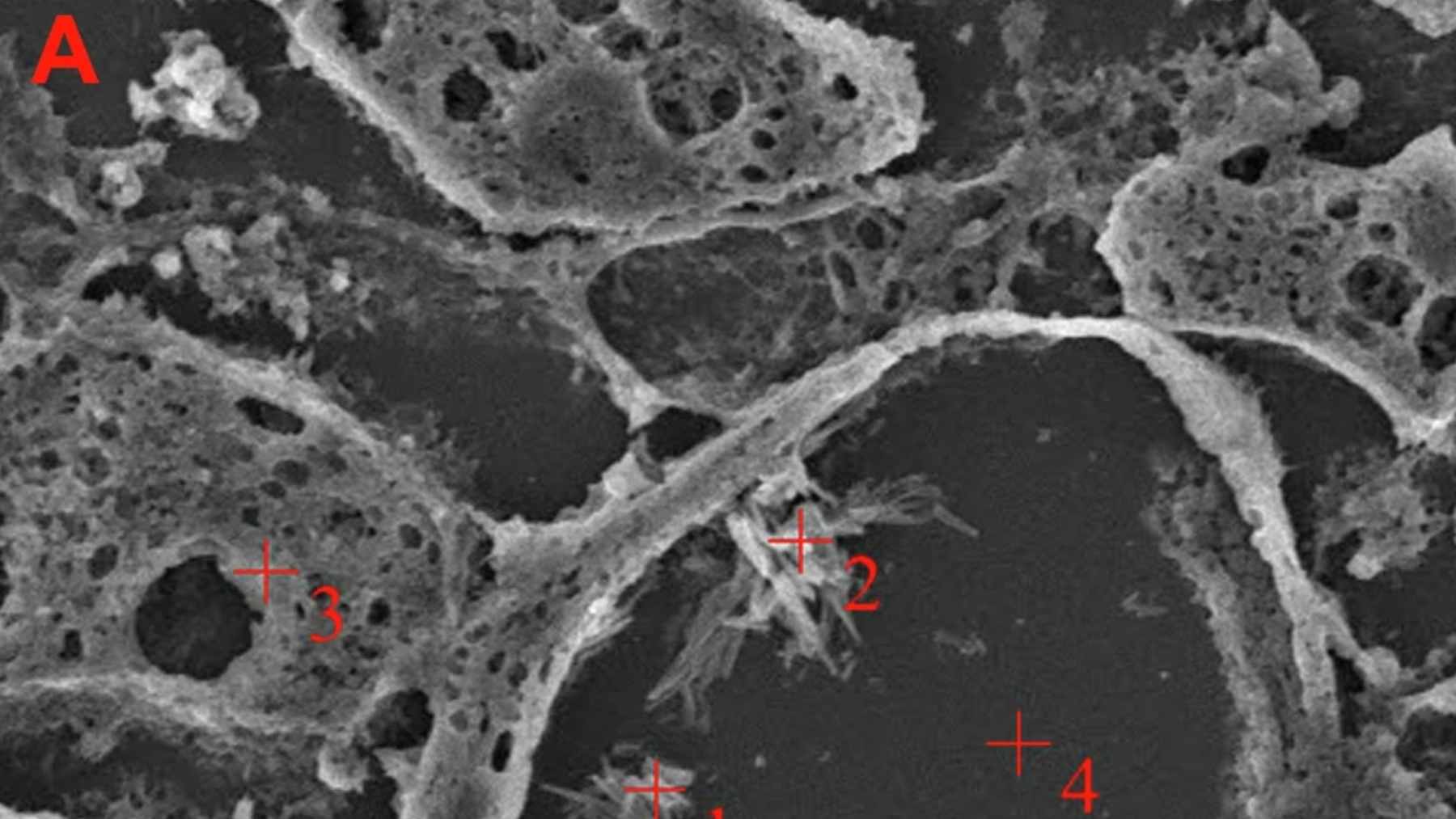

Banerjee and colleagues pulled together two decades of data for the new work, using high resolution images from Landsat and Sentinel‑1 satellites along with detailed motion records from GPS stations drilled into the ice. They focused on the Thwaites Eastern Ice Shelf, a floating extension of the glacier that is partly held in place by a shallow underwater ridge known as a pinning point.

Between 2002 and 2022, the team traced how cracks formed and spread in a narrow strip of ice called a shear zone just upstream of that ridge. In simple terms, this is where chunks of the shelf are sliding past each other at different speeds, stretching and tearing the ice like taffy that is being pulled too hard.

Cracks that feed on themselves

The researchers found that the weakening of the ice shelf unfolded in four phases, with two main stages of fracturing. First came long fractures that ran roughly in the same direction as the ice flow, carving through the shear zone. Later, many shorter fractures appeared that cut across the flow, slicing the ice into smaller, weaker blocks.

This pattern matters because it turns the pinning point from a stabilizing feature into a source of stress. As the damaged ice struggles to hold fast to the ridge, it starts to break more easily. The study shows that once enough fractures had formed, the ice shelf in this region began to speed up, and that faster motion in turn created even more cracks.

Scientists call this a positive feedback loop. For most of us, it may be easier to picture a pothole that grows every time a car hits it. At some point the road fails, and something similar, on a much bigger scale, appears to be happening inside this part of Thwaites.

Beyond melting: internal damage as the main driver

One striking result from the study is that crack growth in the center of the Thwaites Eastern Ice Shelf is now outpacing the ice loss caused by melting at its base. Earlier research strongly emphasized the role of warm ocean water gnawing away at Antarctic ice shelves from below. That process is still important, but here the new work suggests that internal damage and mechanical stress have taken the lead in driving instability.

A related 2022 study in The Cryosphere used computer models and satellite images to show that the same ice shelf had rapidly fragmented in the last few years as stress built up around the pinning point. Together, these findings point to a third way ice shelves can fail: not only by surface melting or by simply lifting off their anchors, but by being pulled apart when weakened ice can no longer handle the forces pushing and pulling on it.

The new research also links changes in the shear zone to speedups farther upstream on the shelf. Small shifts in that narrow strip appear to ripple through the wider ice body, suggesting that local damage can shape how the whole shelf flows and responds to future warming.

What this could mean for coastal communities

If the Thwaites Eastern Ice Shelf collapses, the glacier behind it will likely flow faster into the sea, adding to long‑term sea level rise. On its own, the shelf’s breakup would not instantly flood cities, but it would remove one of the last big brakes on a system that is already contributing about 4 percent of global sea level rise.

The fracture pattern seen at Thwaites may offer a preview for other vulnerable ice shelves around Antarctica that show similar signs of thinning and cracking. A recent science briefing by the British Antarctic Survey concluded that large parts of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, including Thwaites, could be lost by the 23rd century if ice loss keeps accelerating. Other research is more cautious and suggests that some model studies still do not see clear signs of an unstoppable collapse yet, which is why scientists say more measurements and better models are urgently needed.

For people far from the polar ice, these shifts can seem abstract compared with everyday concerns like rent, gas prices, or the electric bill. Yet the pace of change at Thwaites will help determine how much coastal protection future generations will have to build, and how often people in low‑lying neighborhoods will have to mop salt water off their floors. At the end of the day, understanding these hidden fractures is part of planning for a warmer, wetter future.

The main study has been published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface.