Almost 300 million years ago, a small reptile walked through a limestone cave system in what is now Oklahoma. Today, a fragment of its skin, no bigger than a fingernail and as thin as a human hair, is giving scientists the clearest view so far of how our distant relatives first adapted to life on land.

Researchers working at the Richards Spur cave system in southwestern Oklahoma have identified what they describe as the “Oldest-known amniote epidermis as 3D skin cast and several skin compression fossils.” The material, dated to between 289 and 286 million years ago, predates any previously described fossil skin from land vertebrates by more than 20 million years and is reported in the journal Current Biology.

So what can such a tiny scrap really tell us?

A Permian cave that turned into a time capsule

Richards Spur is already famous among paleontologists. The infilled cave system preserves one of the richest assemblages of early terrestrial tetrapods known from the Paleozoic Era. The bones of early reptiles and amphibians there are stained dark brown or black, a clue that they were impregnated by natural petroleum and tar that seeped in from the nearby Woodford Shale.

Those hydrocarbons did more than discolor the fossils. They helped save them.

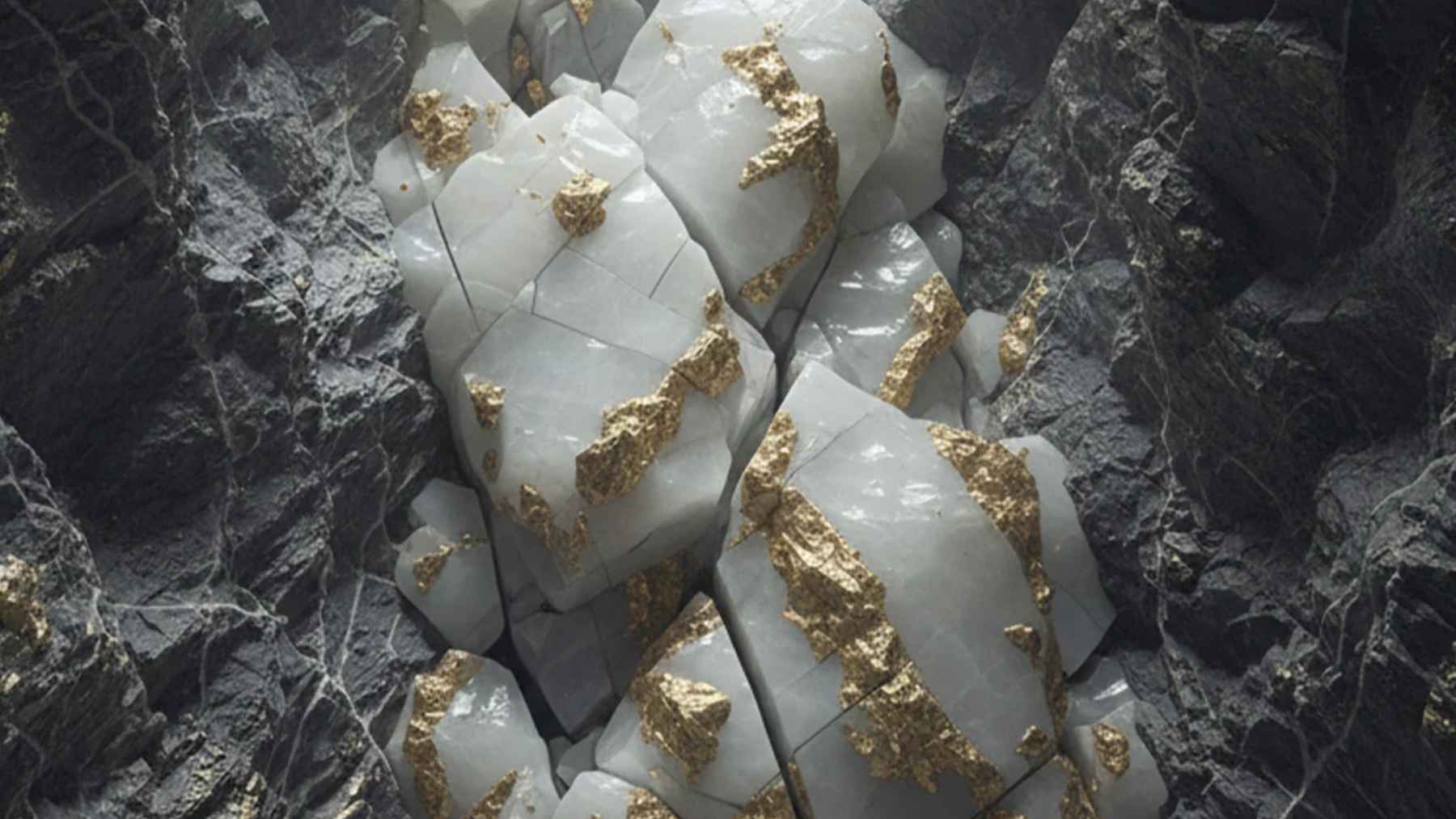

Inside the caves, groundwater was low in oxygen and rich in dissolved minerals. Organic remains fell or washed in, became coated with oil and tar, and were quickly buried in clay-rich sediments. That combination of anoxic water, hydrocarbons, sulfur and fine sediment slowed decay, encouraged early mineralization and created conditions where even fragile soft tissues such as skin could survive.

The new study reports two kinds of skin preservation from this setting. One is a three-dimensional carbonized skin cast that represents the skin itself. The others are compression fossils, where thin sheets of carbon preserve the outer texture of the skin as impressions.

Scales that look like a modern crocodile

Under the microscope, the skin is anything but vague. The three-dimensional cast preserves a pebbled surface of closely packed, non-overlapping tuberculate scales. Each tiny bump is only a few dozen micrometers deep. Between neighboring scales, fine wrinkle like ridges form a kind of hinge region that would have allowed the skin to flex and grow.

The team also describes long, linear epidermal bands preserved on the back of a small reptile called Captorhinus aguti. These bands sit in concentric rows over the vertebral column, just where one would expect to find tough, protective back scales.

Taken together, the isolated skin patches and the bands on Captorhinus show a pattern that, to a large extent, resembles the skin of living reptiles. The pebbled texture is very similar to that of modern crocodiles and some dinosaur “mummies,” suggesting that this style of non-overlapping, tuberculate scaling was already established early in reptile evolution and has changed relatively little since.

The authors argue that this type of cornified epidermis with hinge regions may represent the ancestral condition for amniotes, the broader group that includes reptiles, birds and mammals.

Oil, tar and the chemistry of deep time preservation

The geology behind this discovery reads almost like a forensic report. Chemical fingerprinting of hydrocarbons trapped in bones, stalagmites and tar lumps from Richards Spur shows that they match oils sourced from the Devonian age Woodford Shale, even though that rock unit is no longer present at the surface in this part of Oklahoma.

Over geological time, hydrocarbons migrated upward through fractures in the crust and into the cave system. There they coated carcasses and skeletal remains, creating localized zones with little oxygen and high sulfur content. These pockets were particularly suitable for microbial processes that promote early mineral growth on and within soft tissues.

Soft tissues usually decay rapidly, especially in water. At Richards Spur, the authors suggest that occasional drying inside parts of the cave helped desiccate skin and temporarily halt decay. Later rehydration in mineral rich, hydrocarbon laden groundwater then allowed the skin to be permineralized rather than lost. The result is that rare patches of epidermis survived where they normally never would.

Why ancient skin matters for life on land

Skin is the largest organ in most limbed vertebrates. For early amniotes, it was not just a covering. It was a life support system.

Compared with their amphibian relatives, early reptiles needed an outer barrier that could hold water in, stand up to sunlight and abrasion and still allow growth and movement. The Richards Spur material confirms that a cornified, relatively impermeable epidermis with scale-like protuberances was already in place near the beginning of amniote diversification.

In practical terms, that means the core blueprint for reptile scales, bird feathers and mammal hair follicles may trace back to this kind of skin. The authors propose that the outer epidermal layer in ancestral amniotes later gave rise to more complex follicles for feathers and hair through folding of the same basic tissue.

For modern readers, it is easy to think of fossils as only bones and teeth. This discovery is a reminder that our understanding of ancient ecosystems depends heavily on rare, fragile finds that capture organs we usually never see. When we step outside and feel dry air on our own skin, we are using an adaptation that first took shape in animals very much like the small reptile that left its mark in an Oklahoma cave almost 300 million years ago.

The study was published on the Current Biology website.