On a wind-swept terrace in central Anatolia, archaeologists have uncovered a ring of infant remains around a massive stone structure that had puzzled researchers for years. The latest excavation at Uşaklı Höyük, led by an Italian‑Turkish‑British team, has revealed the bones of at least seven very young children clustered beside a monumental circular building that many specialists now interpret as a sacred space.

The discovery is being called the “Circle of Lost Children”. The infants were not placed in jars or formal graves. Instead, their bones lay in layers of ash mixed with animal remains and broken ceramics, directly tied to the stone circle.

This unusual setting strongly suggests a ritual context rather than ordinary burial practice and may open a rare window on how Hittite communities mourned, honored, or perhaps feared their youngest dead.

A ritual terrace in the shadow of a holy city

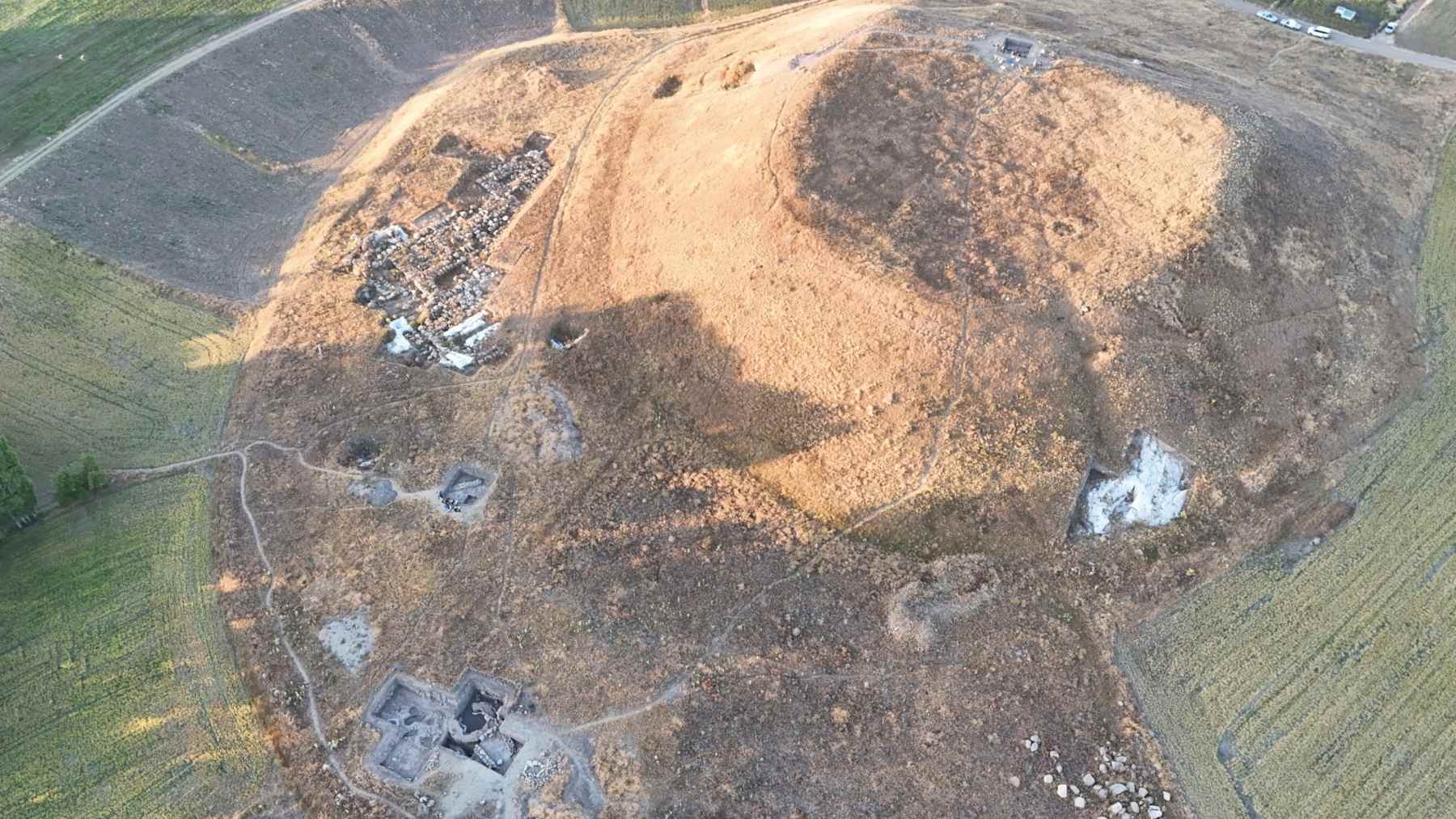

Uşaklı Höyük rises from a fertile plain in Yozgat Province, central Turkey, where a stream feeds fields that have supported farming for millennia. The site consists of a ten‑hectare terrace and a smaller mound and has long been suspected to be the lost Hittite city of Zippalanda, a famous cult center dedicated to a powerful Storm God.

Over the past decade, excavations have revealed monumental granite buildings and a unique circular stone structure on a terrace north of the citadel. Written Hittite sources describe Zippalanda as a place where kings traveled to perform ceremonies for the Storm God, closely tied to weather, crops, and the wellbeing of the land. The combination of large public buildings and this enigmatic circle increasingly strengthens the link between Uşaklı Höyük and that sacred city.

The new infant finds come from Area F, around the circular structure. Archaeologists identified a well‑preserved infant tooth, a nearly complete infant skeleton, a newborn, and partial remains of at least four more perinatal individuals.

The bones appear in small clusters, in ash layers and fill, accompanied by animal bones and sherds from ceramic containers. They are intentional deposits, not bodies simply lost in debris. As excavation director Anacleto D’Agostino put it, the context points to a “differentiated treatment of children in the Hittite world,” one that is almost invisible in surviving texts.

Children, sacrifice, and sacred space

So what were the people of Uşaklı Höyük doing on this terrace three thousand years ago?

Researchers are cautious. There is not yet proof that the infants were killed in ceremonies. Many or all could have died of natural causes in a time when infant mortality was tragically common. What the archaeology makes clear, however, is that their remains were gathered and placed in a carefully maintained ritual zone rather than in ordinary cemeteries.

Scholars compare the pattern to Phoenician and Punic tophets, sanctified precincts where ashes and bones of very young children were buried in urns, sometimes together with small animals. At Uşaklı Höyük, there are no jars, yet the repetition of infant deposits beside a monumental circle strongly hints at a space reserved for special rites involving the youngest members of the community.

If the identification with Zippalanda holds, this terrace may have stood at the intersection of religion, climate, and survival. For Hittite farmers, a failed rainy season meant empty granaries. Appeasing a Storm God who controlled clouds and hail was not an abstract concern. It was about whether fields on the plain below would deliver enough grain to keep families alive through winter.

Feasts, animal offerings, and the ecology of ritual

Animal bones recovered on the terrace deepen that picture. Excavations in and around the circular structure have produced remains of sheep, goats, cattle, pigs, horses, donkeys, deer, and other wild game. Cut marks show butchering and dismemberment. Ceramic residues point to meat and cereal dishes once cooked and served in the same area.

In one large late pit, archaeologists found whole or nearly whole carcasses of several animals, including at least one horse, two donkeys, multiple cattle and caprines, and a hare. The fill likely preserves the aftermath of collective rituals that combined sacrifice, feasting, and large‑scale disposal of animal remains.

Viewed together, the infant deposits and animal offerings sketch a dense ritual landscape. Communities living between fields, steppe, and woodland brought both livestock and wild species onto the terrace.

They cooked, ate, and made offerings while also placing the remains of certain children in the same charged space. The boundary between caring for the land and caring for the dead seems to have blurred at this Hittite sanctuary.

Ancient DNA and a new look at Hittite lives

One tiny tooth could push the story even further. The infant tooth found above one of the stone pavements is now being analyzed by the Human_G molecular anthropology laboratory at Hacettepe University in Ankara. This lab specializes in ancient DNA and is currently the only facility in Turkey dedicated entirely to such analyses.

From that single piece of enamel, scientists hope to obtain radiocarbon dates, genetic information about the child, and clues to the broader makeup of the Hittite population at Uşaklı Höyük.

Combined with ongoing studies of seeds, charcoal, and animal bones, the genetic data could reveal where families came from, what diseases they carried, how they used local plants, and how resilient their food systems were in the face of environmental change.

Why this matters for how we see the past

At first glance, the “Circle of Lost Children” feels distant from everyday concerns like rising power bills or heatwaves in modern cities. Yet the story unfolding on this Anatolian terrace is, to a large extent, about how people respond when their world feels fragile.

For the Hittites who walked up to that stone circle, the wind on the plateau, the behavior of clouds, and the health of newborns were all part of the same delicate balance between humans, gods, and landscape.

Their rituals turned children, animals, and food into messages aimed at the sky. Today, scientists use climate models and satellite maps instead of sacrifice, but the underlying anxiety about rain, harvests, and long‑term habitability is not entirely different.

Archaeology at Uşaklı Höyük reminds us that environmental history is also family history. It lives in burned floors and broken dishes and in the smallest of teeth. Every bone, every seed, every ash‑stained stone helps reconstruct how past societies tried to live with an unpredictable environment and how high the emotional cost of that struggle could be.

The official statement on these findings was published on the University of Pisa website.