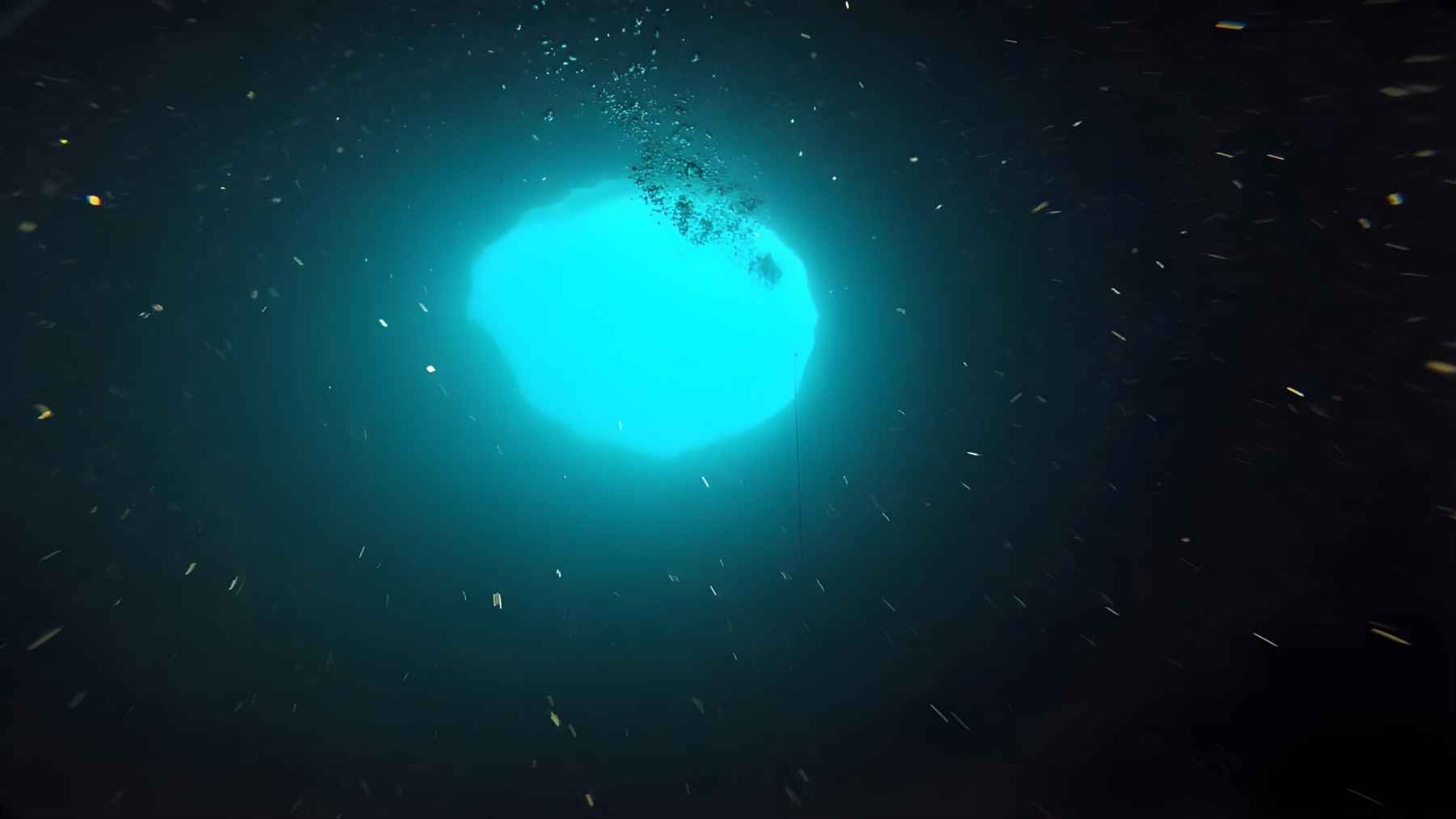

Beneath the calm surface of Chetumal Bay in southern Mexico, the seafloor suddenly falls away into a near-bottomless void. This chasm, known as Taam Ja (which means “deep water” in Mayan), has just been confirmed as the deepest known blue hole on the planet, reaching at least 420 meters below sea level and still with no bottom in sight.

For scientists, that depth is not just a record. It turns Taam Ja into a natural test lab for extreme life, hidden groundwater flows, and even the kind of chemistry that might support organisms in the dark oceans of distant moons.

A giant sinkhole hiding in a shallow bay

Taam Ja sits in the middle of Chetumal Bay near the Mexico-Belize border, inside the Chetumal Bay Manatee Sanctuary, a state-protected area. The surrounding estuary is only a few meters deep, yet the blue hole opens as a nearly circular pit covering around 13,700 square meters, with walls that drop at slopes steeper than 80 degrees and form a huge conical structure.

Local knowledge helped put it on the map. Fishermen had long noticed an oddly calm patch of water where waves seemed to flatten out. In 2021, researchers from El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR) used sonar, scuba dives and water sampling to survey the feature and found it plunged to about 274 meters. That first campaign ranked Taam Ja as the second-deepest known blue hole on Earth.

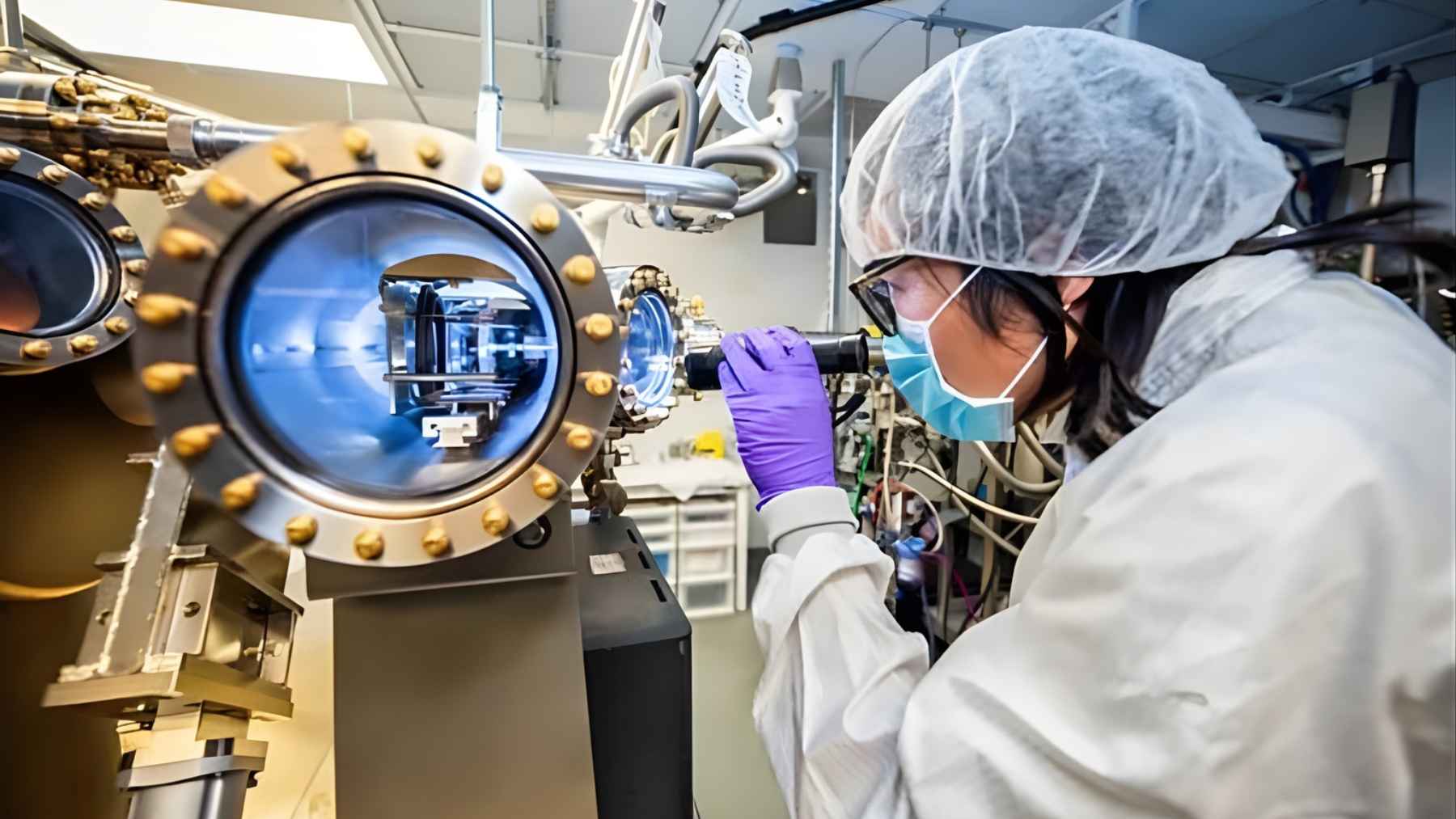

New measurements have now pushed the story much deeper. In December 2023, the team lowered a conductivity, temperature, and depth profiler into the hole and recorded water depths of 416 and 423.6 meters without ever hitting bottom, surpassing the famous Dragon Hole in the South China Sea, which reaches about 301 meters.

How blue holes form and why Taam Ja is special

Blue holes are vertical marine caves carved in limestone or other soluble rock. They formed during past ice ages when sea level sat roughly 100 to 120 meters lower than today and rainwater slowly dissolved the exposed bedrock into caverns. When the oceans rose again, ceilings collapsed, the caverns flooded, and the openings became the dark circles we see from above.

Most well-known examples, such as the Great Blue Hole in Belize and Dean’s Blue Hole in the Bahamas, are already impressive at 125 and 202 meters deep. Taam Ja is more than twice as deep as those Caribbean icons and sits in an estuary rather than on an open platform reef, which makes its size and setting particularly unusual.

Inside, the water column is sharply layered. Earlier work in Taam Ja identified a shallow zone with low oxygen, a mid depth chemical transition, and deeper waters that are completely anoxic. In other blue holes, scientists have found that such oxygen poor layers can contain poisonous clouds of hydrogen sulfide and support dense mats of bacteria that feed on sulfur compounds instead of sunlight.

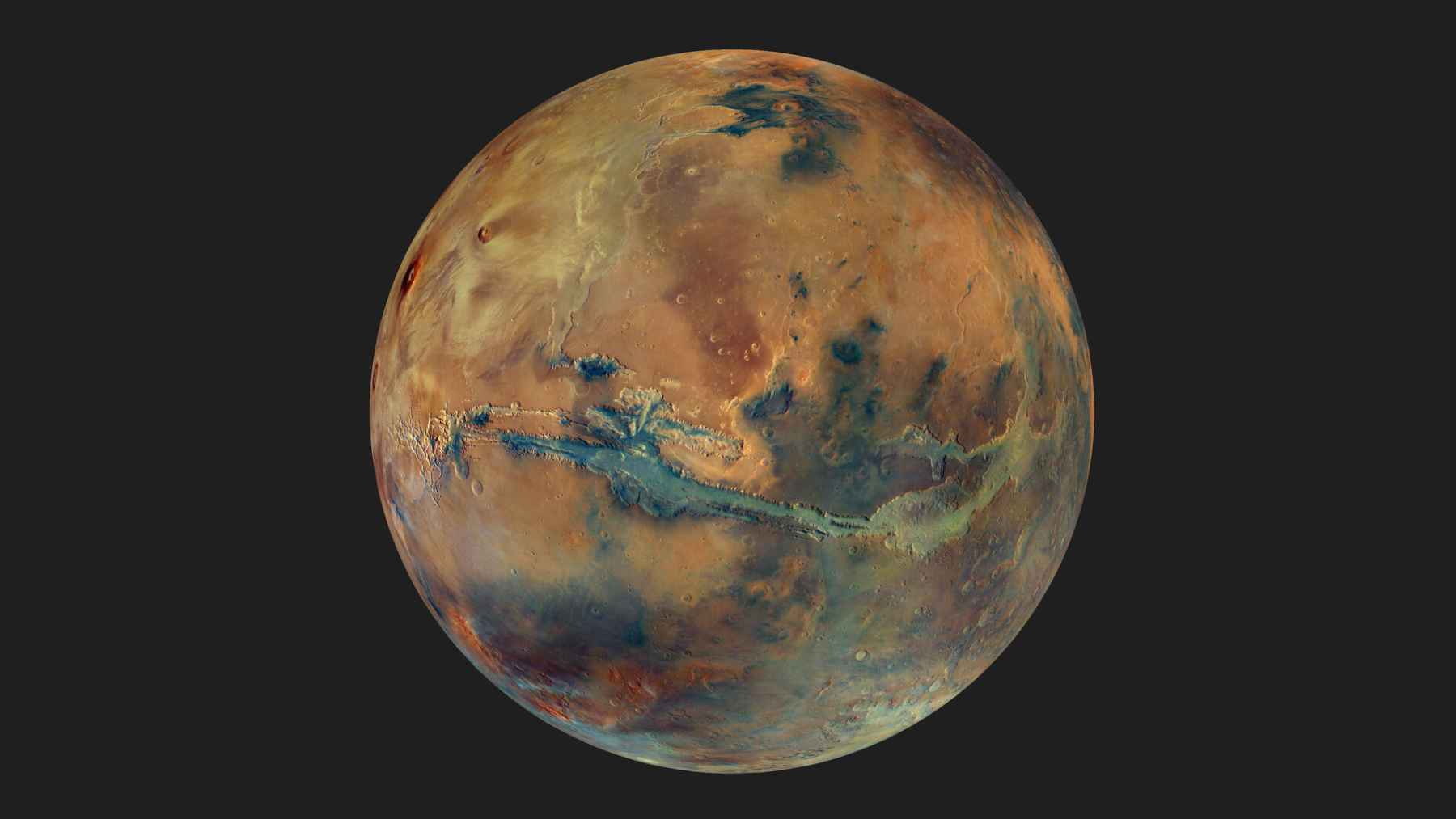

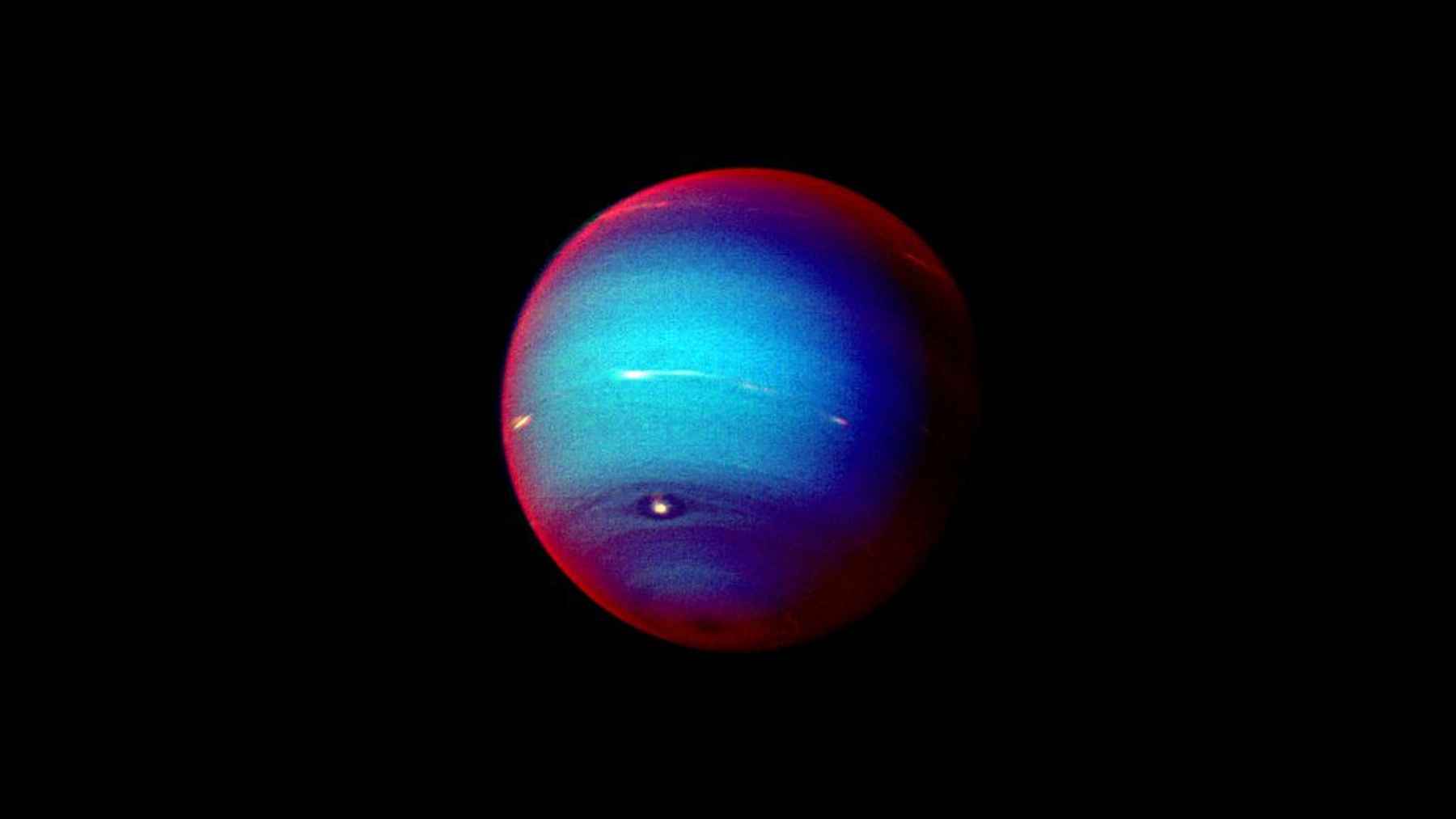

That kind of chemistry is exactly what excites astrobiologists. Microbes discovered in Bahamian blue holes live in darkness, breathe sulfur and thrive where almost nothing else can, and researchers have suggested they could resemble possible life in the buried oceans of Europa or Enceladus, the icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn.

A layered ocean inside the bay

The new study of Taam Ja did more than update the depth record. It also traced how temperature and salinity change from the surface down through more than 400 meters. Below about 400 meters, conditions start to resemble those in the Caribbean Sea and nearby coastal reef lagoons, which suggests that the blue hole might be connected to the open ocean through hidden caves or tunnels.

In practical terms, that means Taam Ja might act like a deep window into regional groundwater and coastal circulation. Any contaminants or nutrients that seep through the surrounding karst could eventually move in and out of the hole, then on toward coral reefs and seagrass beds that local communities depend on for food and tourism.

Scientists say they still need advanced navigation tools to map those pathways and to figure out how far the cave network extends.

Time capsule of climate and life

Blue holes elsewhere have already shown how powerful these features can be for understanding Earth’s history. In the Bahamas, stalagmites and sediments from flooded caverns preserve detailed records of past sea level, shifts in African dust and intense droughts over millions of years.

Fossils of extinct tortoises, crocodiles and even early island peoples have been found in similar sinkholes, protected by the dark, oxygen-starved water.

Researchers working on Taam Ja note that Western Caribbean blue holes have been far less studied than those in the Bahamas, even though they can offer the same clues about past climate and regional hydroclimate variability. For a planet that is trying to understand rising seas and changing rainfall, that kind of archive is valuable.

What comes next

For now, Taam Ja feels a bit like a mystery at the edge of town, hiding in plain sight beneath waters that many people cross without a second thought. Reaching its true bottom will require specialized equipment and careful planning, both for safety and to avoid disturbing fragile microbial communities that may live in its deepest layers.

As those efforts move ahead, the blue hole is likely to play a growing role in both regional conservation and global science. It can help Mexico refine protection for its coastal aquifers and ecosystems, and it can help researchers test ideas about how life copes with darkness, pressure and chemical extremes.

The study was published in Frontiers in Marine Science.