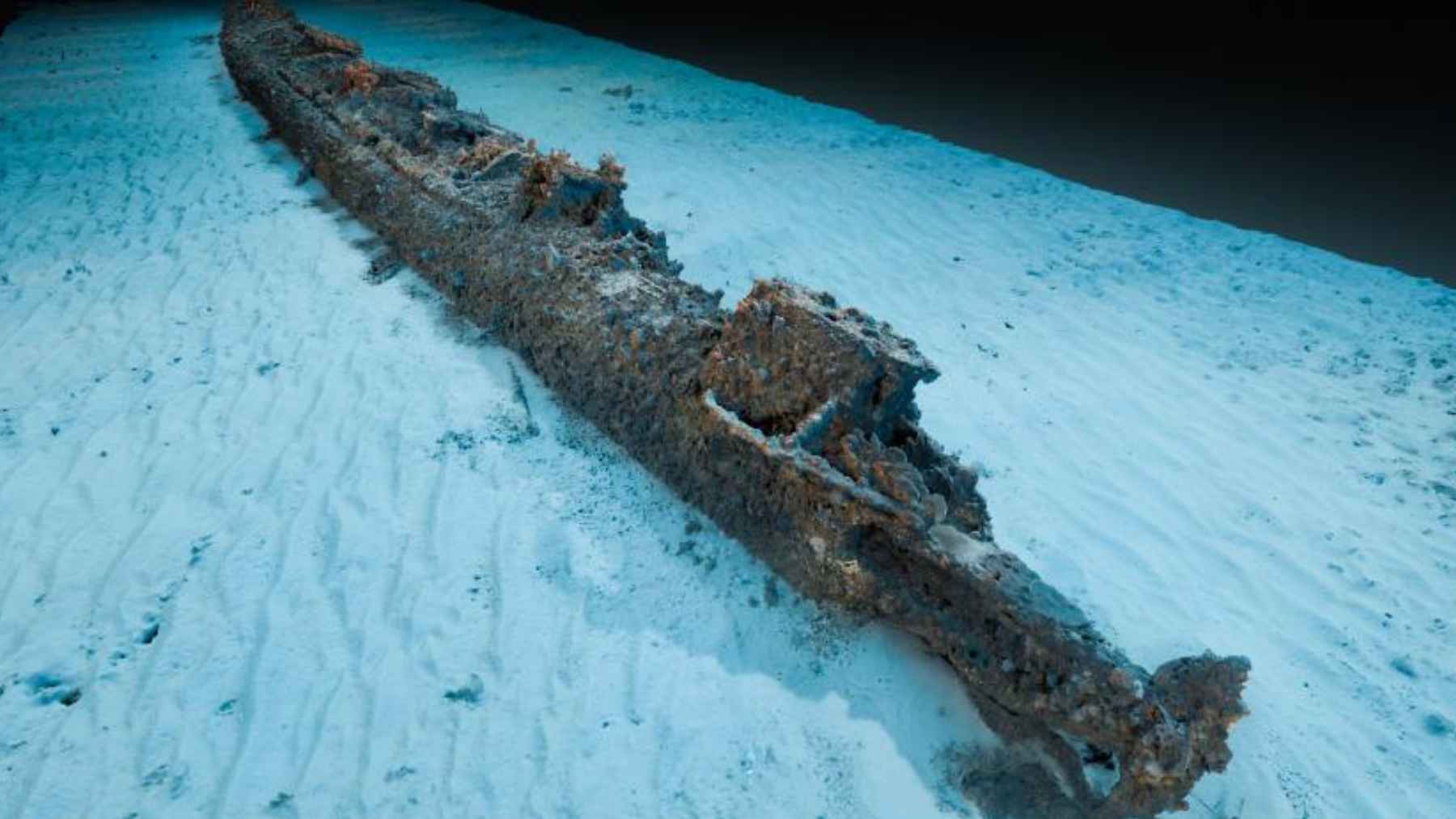

Deep below the Pacific Ocean, far beneath the seafloor and well out of reach of any drill, scientists have found something that does not fit the textbook picture of our planet.

New seismic models reveal giant zones of unusually fast rock in the lower mantle that look like the remains of old tectonic plates, yet they sit under open ocean and continental interiors where no subduction zones are known to exist.

If that sounds puzzling, the researchers feel the same way. One of these structures lies under the western Pacific, roughly 900 to 1,200 kilometers down, in a region with no geological record of any plates having plunged into the mantle in the last 200 million years.

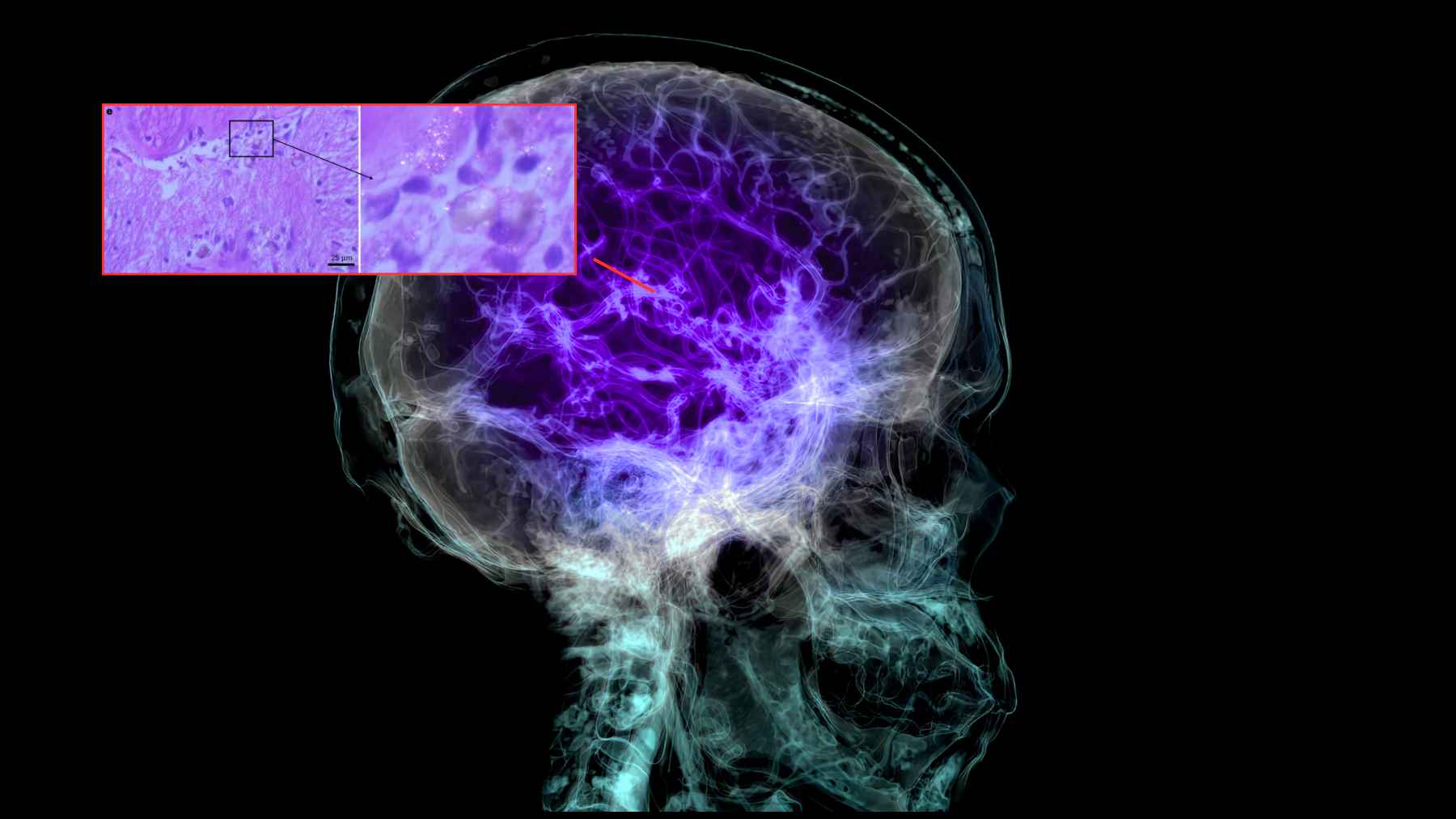

Turning earthquakes into a planetary ultrasound

So how do you “see” a mystery that deep without ever going there? Geophysicists use earthquakes. Each big tremor sends waves rippling through the planet. Seismographs record when those waves arrive, and how they bend and bounce, a bit like a global medical scan.

For decades, most global mantle images came from measuring only the travel times of a few easily identified waves, mainly the direct P and S phases.

That approach produced the first three-dimensional maps of the mantle but it is strongly biased toward regions with lots of earthquakes and dense seismic networks, such as around the Pacific Rim. Large swaths under old ocean plates or quiet continents remained fuzzy.

The new study takes a different route. The team at ETH Zurich and collaborators used “full waveform inversion,” a method that tries to match complete earthquake seismograms instead of cherry picking a handful of wave arrivals.

This pulls in reflected and refracted waves that are usually ignored and boosts sensitivity throughout the mantle, even beneath areas that lack nearby quakes or instruments.

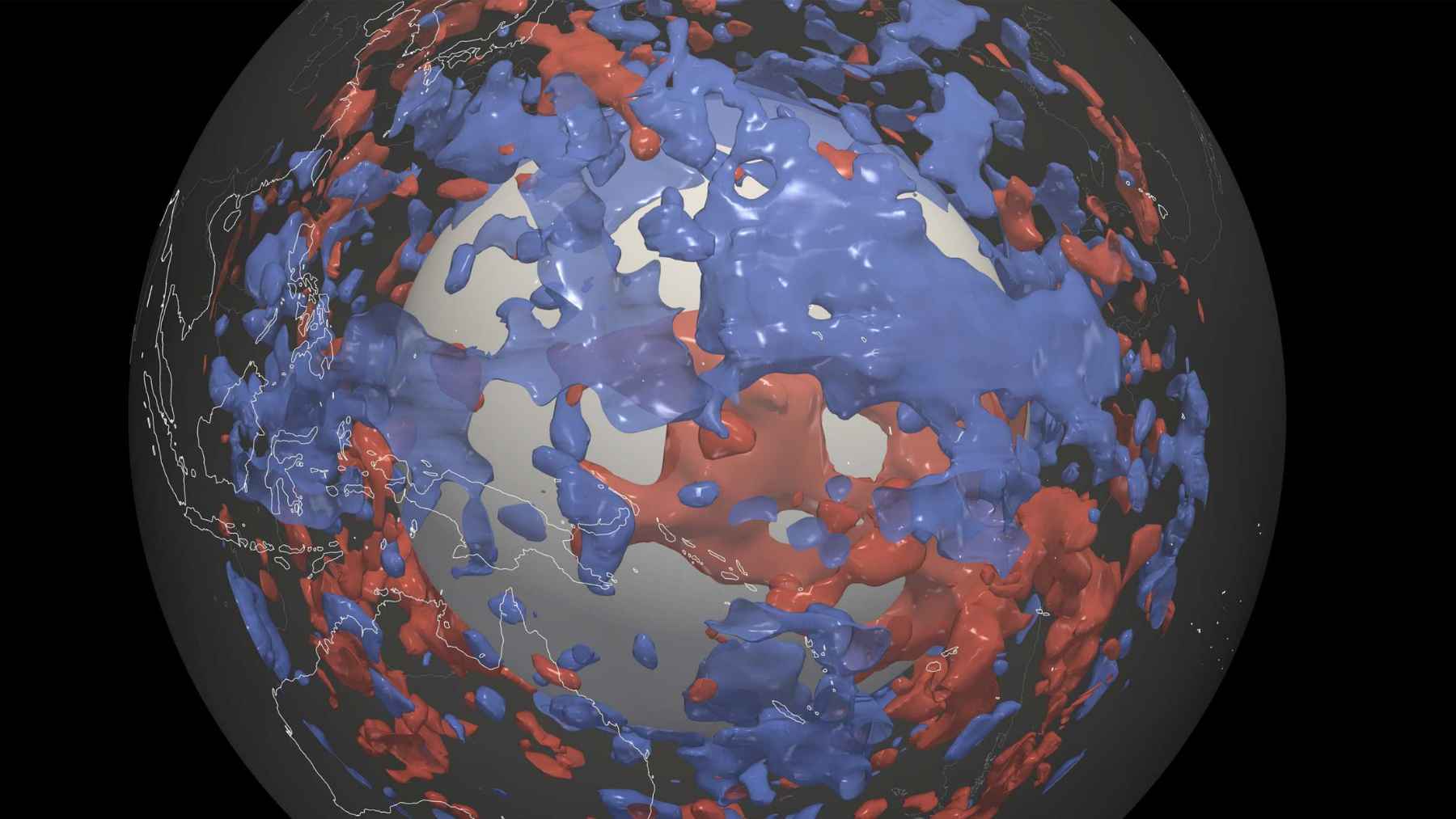

Running this kind of model is not something you do on a laptop at the kitchen table. The researchers relied on the Piz Daint supercomputer in Switzerland to crunch data from many earthquakes and build a high-resolution global model called REVEAL.

A forest of hidden anomalies

What REVEAL shows is a mantle that is much more heterogeneous than previous maps suggested. In the mid and lower mantle, the team finds many large regions where seismic waves move faster than average, not only beneath familiar subduction zones but also under the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian oceans and under stable continental interiors.

Fast wave zones usually indicate rock that is cooler, denser or chemically different from its surroundings. Traditionally, geophysicists interpreted such anomalies almost entirely as “slabs,” the cold remains of old ocean plates that have sunk into the mantle at subduction zones and kept sinking more or less vertically over tens of millions of years.

That simple picture made life easier. It allowed researchers to use these anomalies as direct tracers of where plates once dove into the mantle, how fast they sank and even to estimate how deep Earth’s internal conveyor belt might have buried carbon over geological time.

The new model unsettles that neat story. When the team compared their fast anomalies with detailed reconstructions of past plate boundaries, they found that at most about 60% to 70% of reconstructed subduction zones line up with positive wave speed regions in the lower mantle, and the statistical correlation largely disappears when they account for sampling biases.

In other words, many of the “blobs” are not where subducted plates are expected to be.

If not only slabs, then what

Lead author Thomas Schouten sums up the puzzle bluntly. With the new model, the team can see anomalies “everywhere in the Earth’s mantle,” yet they still “do not know exactly what they are or what material is creating the patterns” they see.

The study suggests that these structures may have diverse origins. Some may indeed be pieces of old plates. Others could be ancient, silica-rich mantle material that formed about four billion years ago and somehow survived the slow churning of convection.

Still others might be zones where iron-rich rocks have gradually pooled as mantle currents shuffled material around over billions of years.

Previous geochemical and geodynamic work has long hinted that Earth’s mantle is a “marble cake” of mixed rock types rather than a perfectly-blended layer. The new seismic images line up with that view and show that compositional differences can mimic, or mask, temperature variations in the wave speed signal.

Why it matters for a living planet

At first glance, all this sounds very deep and very far from daily life. Yet the same mantle circulation that shapes these hidden structures also drives plate motions, helps feed volcanoes and ultimately influences long-term sea level and the slow cycling of carbon between the interior and the atmosphere.

Some earlier climate reconstructions have used deep mantle slab images as a key input, for example when estimating past atmospheric carbon dioxide levels.

If many fast anomalies are not simple cold slabs, then scientists will need to handle that uncertainty with care. The planet’s interior engine still runs; we are just realizing it has more moving parts than we thought.

For Schouten and colleagues, the next step is clear. They want to go beyond mapping wave speeds and start pinning down the actual material properties that could produce them, from mineral mix to temperature to grain size.

One thing is already obvious. As our “ultrasound” of Earth improves, the familiar picture of a tidy, layer cake planet gives way to something more intricate. Hidden structures under the Pacific are a reminder that even on our well-studied home world, there are still deep surprises waiting.

The study was published in Scientific Reports.