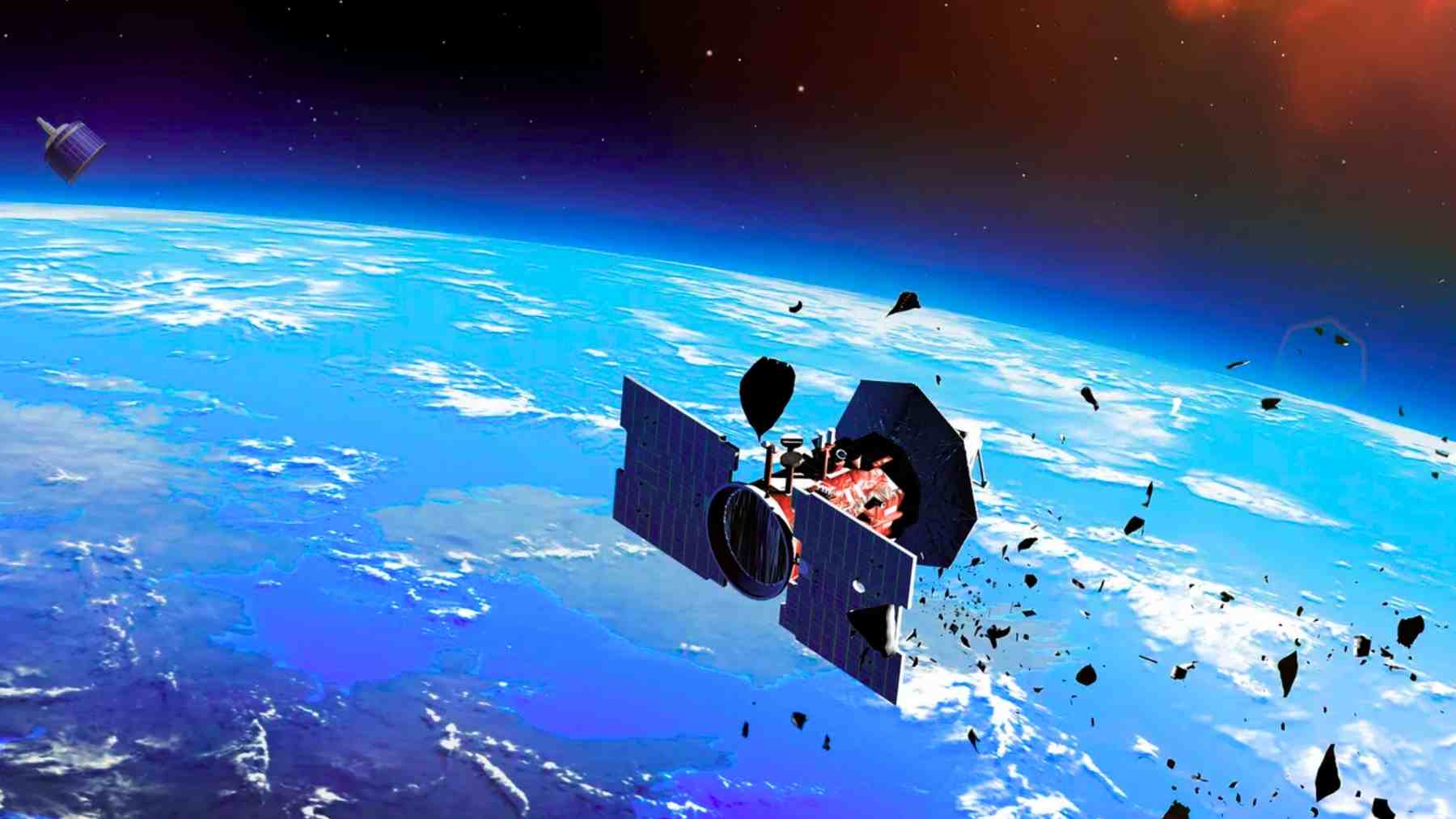

In early January, the US Federal Aviation Administration quietly issued its first safety alert telling airlines to prepare for falling debris from failed rocket launches. The guidance, known as SAFO 26001, follows a 2025 SpaceX Starship test flight that broke apart over the Caribbean and forced three aircraft carrying about 450 people to maneuver around a debris field.

What does that actually mean for someone watching their departure time creep later on an airport screen?

A near miss over the Caribbean sky

The alert explains that space launches can have “catastrophic failures resulting in debris fields” and urges operators to build rocket activity into preflight planning and day‑to‑day risk management. SAFOs are advisory rather than new law, but airlines usually treat them as serious guidance for training and procedures.

The January 2025 Starship mishap showed why. According to internal FAA records cited by several outlets, debris from the giant rocket lingered over parts of the Caribbean for nearly an hour while controllers slowed or diverted traffic. Three flights, including a JetBlue service to San Juan and an Iberia transatlantic run, ultimately declared fuel emergencies as they threaded around the risk zone.

SpaceX has insisted that “no aircraft have been put at risk,” and the affected airlines say their jets stayed clear of the worst of the debris. Even so, the FAA’s own description of a “potential extreme safety risk” shows how quickly a single-launch anomaly can ripple through a busy airspace system.

Launch boom, crowded skies

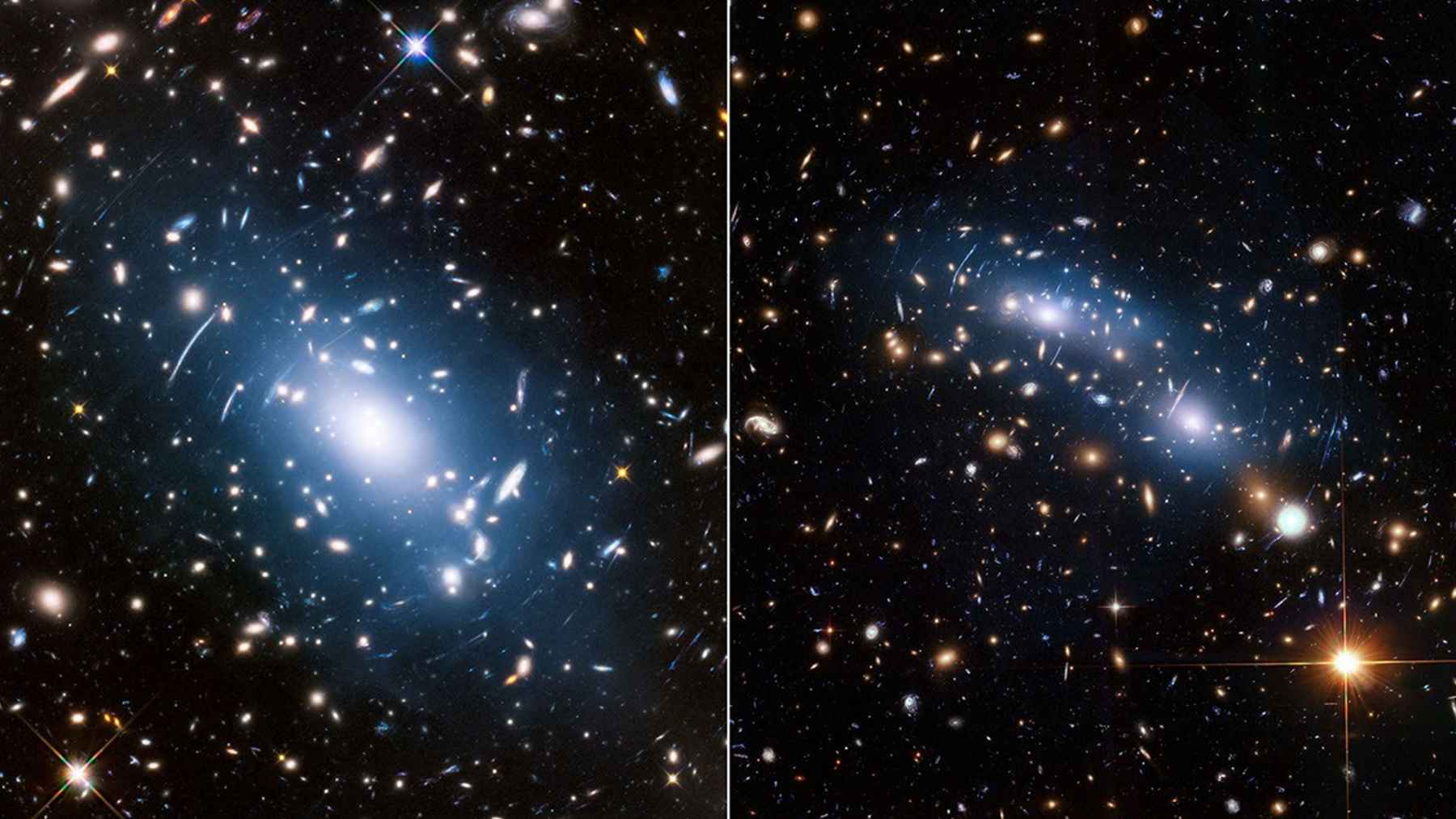

Behind this alert is a simple trend. Launch activity has surged. FAA figures show licensed commercial space operations climbing from just 14 in 2015 to 148 in fiscal year 2024, with SpaceX accounting for more than 80% of those launches.

The agency’s latest ten-year forecast expects annual licensed launches and reentries to rise into a range between 259 and 566 by 2034. More rockets means more temporary no-fly zones, more last-minute reroutes and, at times, more aircraft burning extra fuel to wait or detour around hazard areas.

Scientists warn that this is not only an air traffic headache. It is also an environmental problem unfolding high above the usual weather.

When space junk becomes air pollution

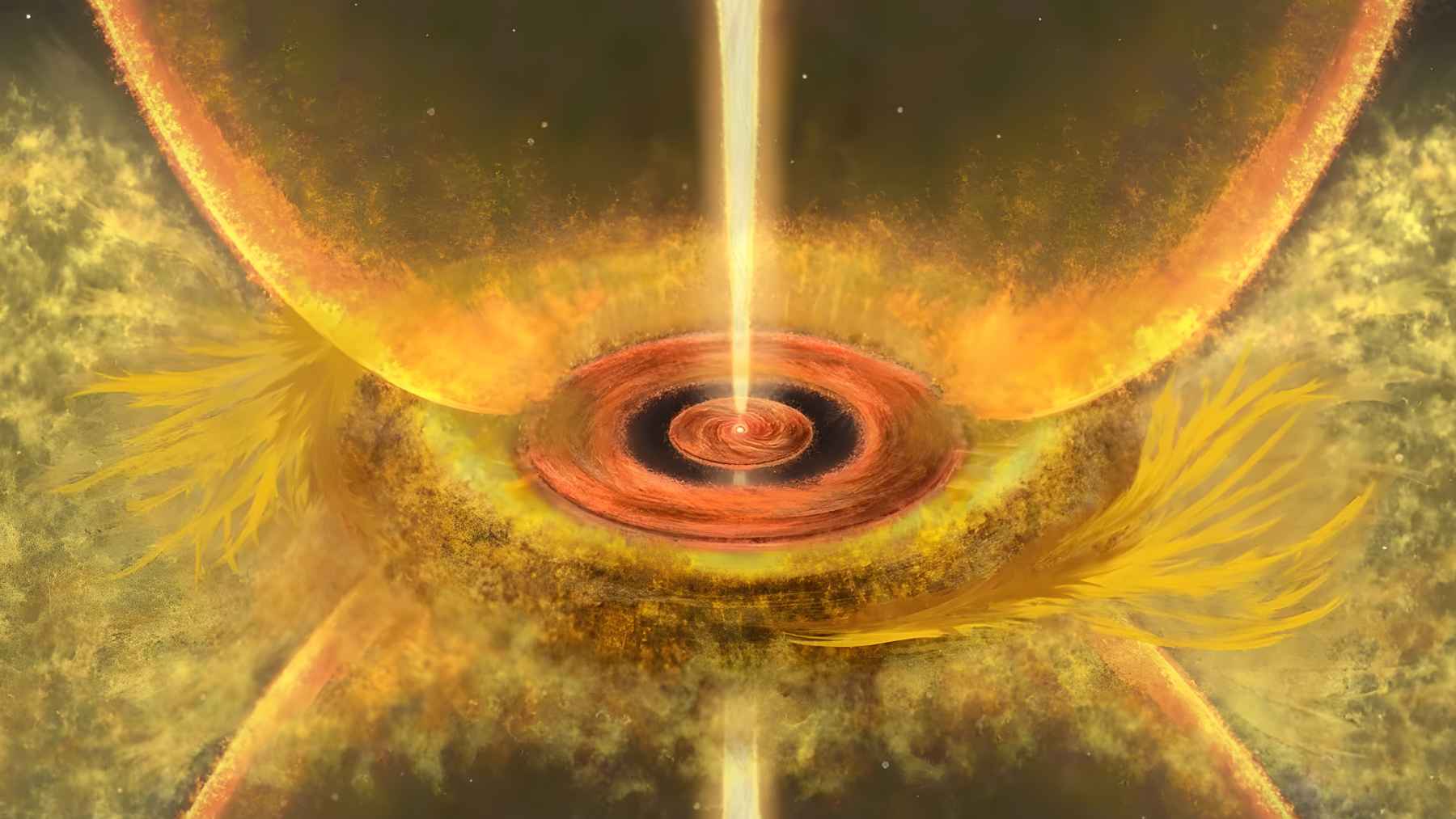

Studies led by NOAA and university researchers find that black carbon from rocket exhaust accumulates in the stratosphere, where it can warm the air far more efficiently than soot released near the ground. Modeling work suggests that if rocket soot emissions grow to several times today’s levels, they could raise stratospheric temperatures by around 1.5 degrees Celsius and contribute to ozone loss.

At the same time, reentering satellites and upper stages are leaving a metallic fingerprint overhead. Measurements of stratospheric aerosol particles show that about 10% of larger droplets now contain aluminum and other metals that match spacecraft materials. A related study estimated that satellites burning up in 2022 increased aluminum in parts of the upper atmosphere by nearly 30% above natural levels.

A recent NASA technical assessment concludes that emissions from launches and reentries already affect every layer of the atmosphere and notes that the mass of material arriving from spacecraft and debris has been doubling roughly every three years. That growth is driven in large part by mega‑constellations and increasingly-frequent test flights of heavy vehicles such as Starship.

Who carries the risk?

There is also a fairness question hiding behind the technical details. A 2024 analysis in the journal Acta Astronautica argues that as both air traffic and rocket launches increase, the probability of an aircraft encountering reentering debris will grow. The authors say uncontrolled reentries let space operators shift risk and potential economic costs onto airlines and passengers, and they call for a global move to controlled reentries that steer hardware away from busy routes.

For travelers, the impact shows up in familiar ways. A longer flight path around a launch corridor. A holding pattern that keeps the seat belt sign on. Extra fuel burned to stay safe, even as aviation tries to cut its own climate footprint.

None of this means spaceflight has to stop. It does suggest that rockets, like cars and aircraft, will need clearer environmental rules and smarter technology so that the push to orbit does not undermine safety or climate progress back on Earth. The new FAA alert is framed around debris, but to a large extent it opens a wider conversation about how to keep the space race compatible with a livable atmosphere.

The Safety Alert for Operators was published by the Federal Aviation Administration.