If you picked up a dull gray rock from a South African outcrop, would you guess it holds chemical memories of some of Earth’s earliest microbes?A new study says that is exactly what is hiding there, and that artificial intelligence can help us hear those very faint echoes.

An international team led by researchers at the Carnegie Institution for Science has used machine learning to find molecular fingerprints of life in rocks up to 3.33 billion years old. Their method also picks out signs that photosynthetic organisms were already at work in rocks about 2.52 billion years old, long before oxygen flooded the atmosphere.

In practical terms, that nearly doubles the time window in which scientists can read biochemical traces, pushing the molecular record of life back from about 1.6 billion years to more than 3.3 billion years.

Teaching a computer to “smell” old life

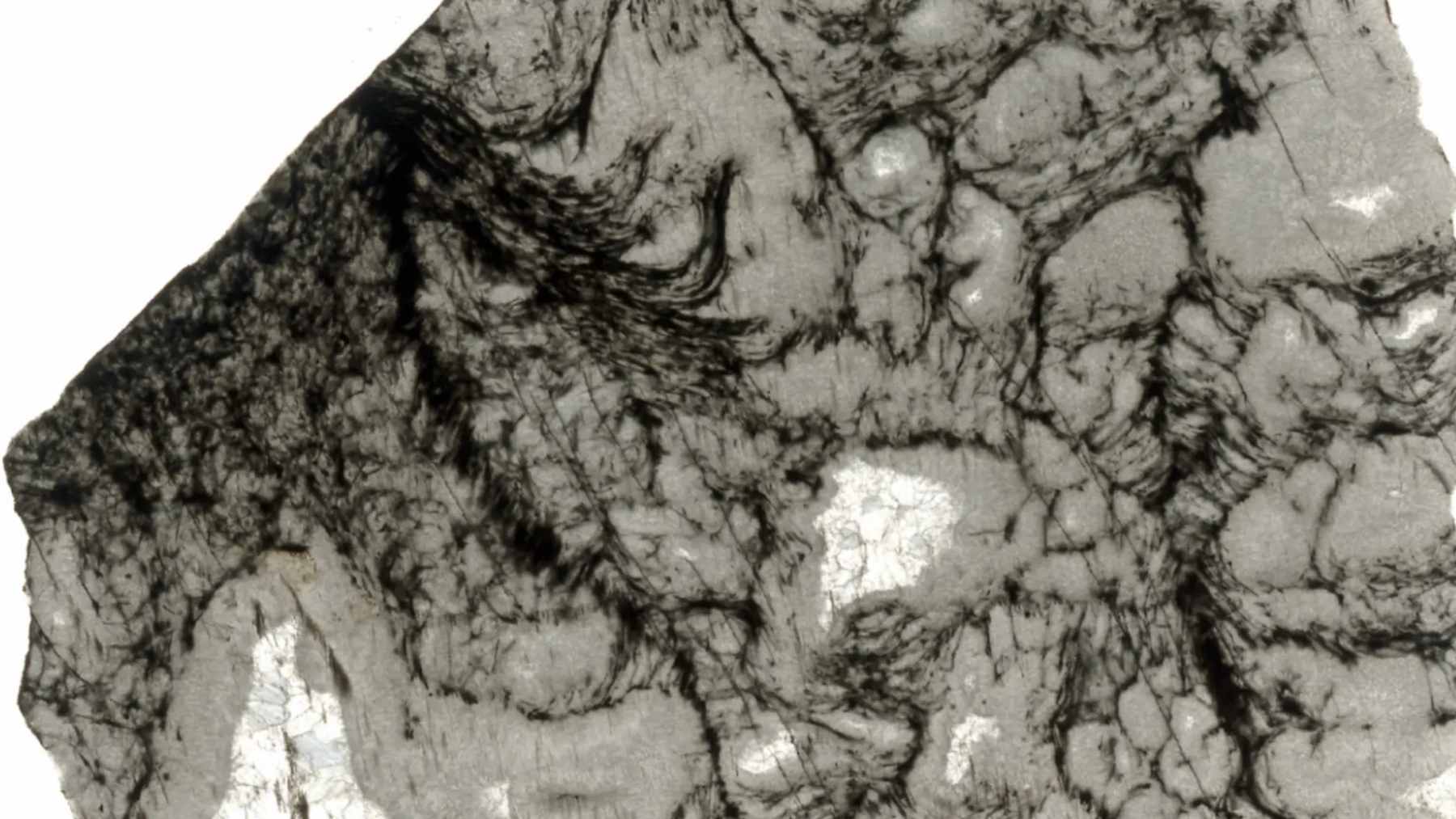

Instead of hunting for obvious fossils or intact pigments, the team looked at what is left when biology has been cooked, squashed, and chemically altered for billions of years. They took 406 samples that contain carbon-based molecules, including modern plants and animals, fossil coals and shales, meteorites, and lab-made mixtures.

Each sample was heated so its organic matter broke into a cloud of smaller molecules, then run through gas chromatography and mass spectrometry. That process separates the fragments and measures their mass, creating an intricate chemical “barcode” for every rock or tissue.

On their own, those barcodes are far too complex for the human eye. So the researchers trained a random forest machine learning model to sort the patterns into categories such as biogenic versus abiogenic, and photosynthetic versus non photosynthetic. In many of the tests, the system correctly separated living from non-living sources more than 90 percent of the time, and often closer to 95 to 98 percent.

It is a bit like teaching a computer to recognize a song from a few muffled notes coming through a wall. The original tune may be distorted, but the pattern is still there.

Oldest chemical hints of photosynthesis

The real excitement starts when the trained model is turned loose on ancient rocks whose origins have been debated for years.

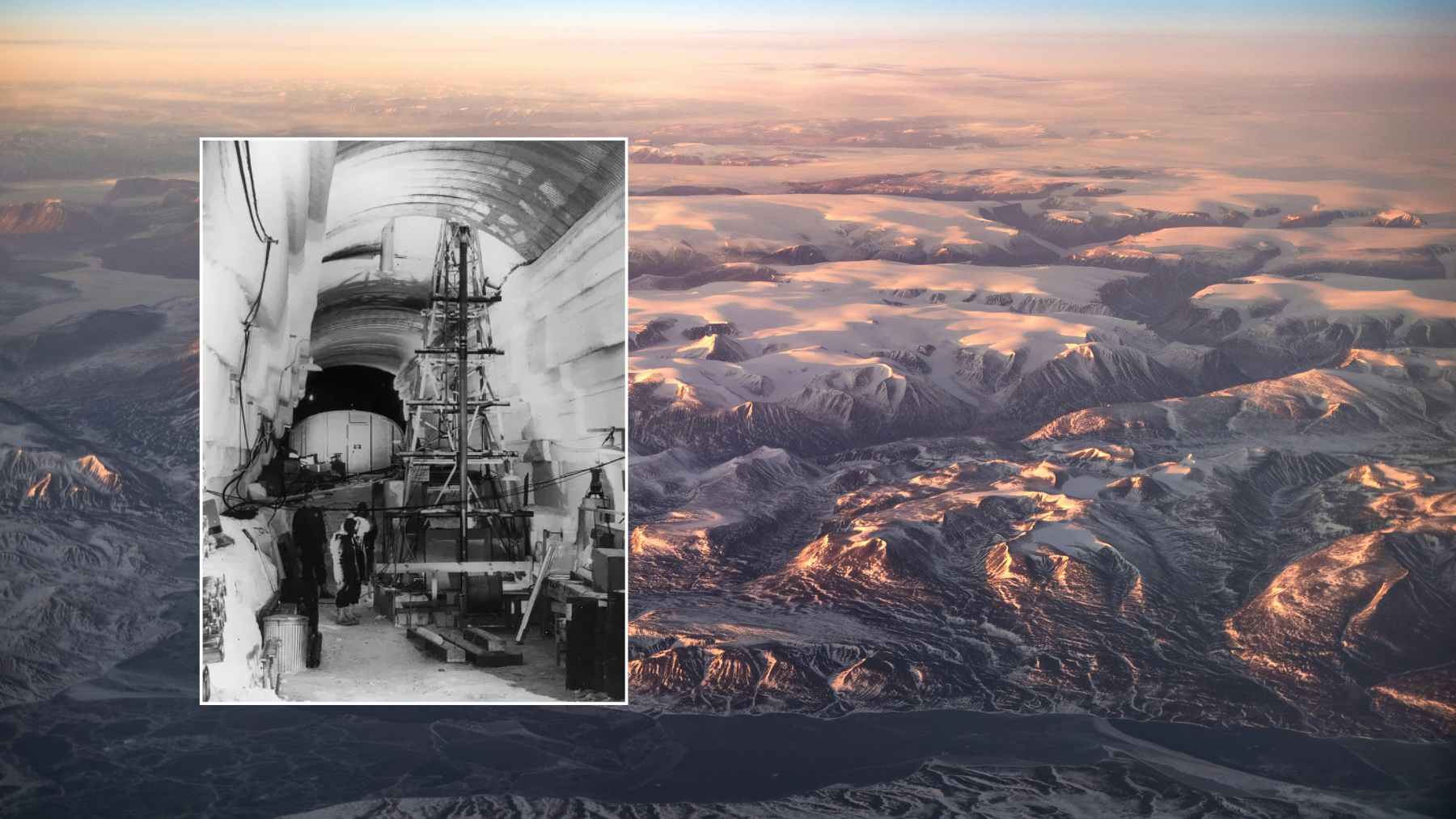

The team found that organic material from the 3.33 billion-year-old Josefsdal Chert in South Africa behaves like degraded biological matter, not like meteoritic or synthetic organics.

Even more striking, rocks about 2.52 billion years old from the Gamohaan Formation in South Africa and about 2.30 billion years old from the Gowganda Group in Canada cluster with samples from photosynthetic organisms.

That supports the idea that microbes using sunlight to make organic matter were already widespread hundreds of millions of years before the Great Oxygenation Event that transformed Earth’s atmosphere. For the air you breathe on your way to work, these microscopic pioneers were doing the heavy lifting very early.

The method also flags several famous rock units, such as parts of the Dresser Formation in Australia, as more likely non-photosynthetic, or at least so altered that any original photosynthetic signal has been blurred.

Rewriting Earth’s environmental backstory

Why does this matter for ecology and climate today, not just for geology fans with field hats?

Early photosynthesis is tied directly to Earth’s first big environmental makeover. Once oxygen producing microbes got going, they gradually changed the chemistry of the oceans and the air, paving the way for ozone, complex food webs, and eventually forests, animals, and human lungs.

Until now, scientists mostly relied on shapes in rocks, carbon isotopes, and a limited set of molecular fossils to time that revolution. Those tools are powerful, but they can be ambiguous, especially when rocks have been heated or deformed. By squeezing more information out of the molecular “crumbs” that remain, the new approach adds another line of evidence to that story.

It also highlights a sobering pattern. The older the rocks, the fewer samples the model can confidently label as biogenic. That trend likely reflects just how thoroughly geological processes erase or scramble organic matter through deep time.

Dress rehearsal for finding life beyond Earth

There is another reason astrobiologists are paying attention. If AI can spot the chemical afterglow of microbes that lived more than three billion years ago on Earth, it may help recognize life in even harsher conditions elsewhere.

The same kind of analysis could be applied to samples from Mars, or to future missions that collect icy spray from worlds like Enceladus or Europa. Reuters reports that NASA has already supported follow-up work to adapt the technique for planetary exploration.

Of course, the method is not magic. Some samples fall into a gray zone where the algorithm cannot be sure. The authors also note that they need many more well-characterized abiogenic samples, and a broader training set that includes a wider range of photosynthetic styles, to reduce the risk of false positives.

Even so, the study shows that Earth’s oldest rocks still carry surprisingly rich chemical information about the planet’s first ecosystems. With a bit of machine learning and some patient lab work, those silent stones are starting to talk.

The study was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.