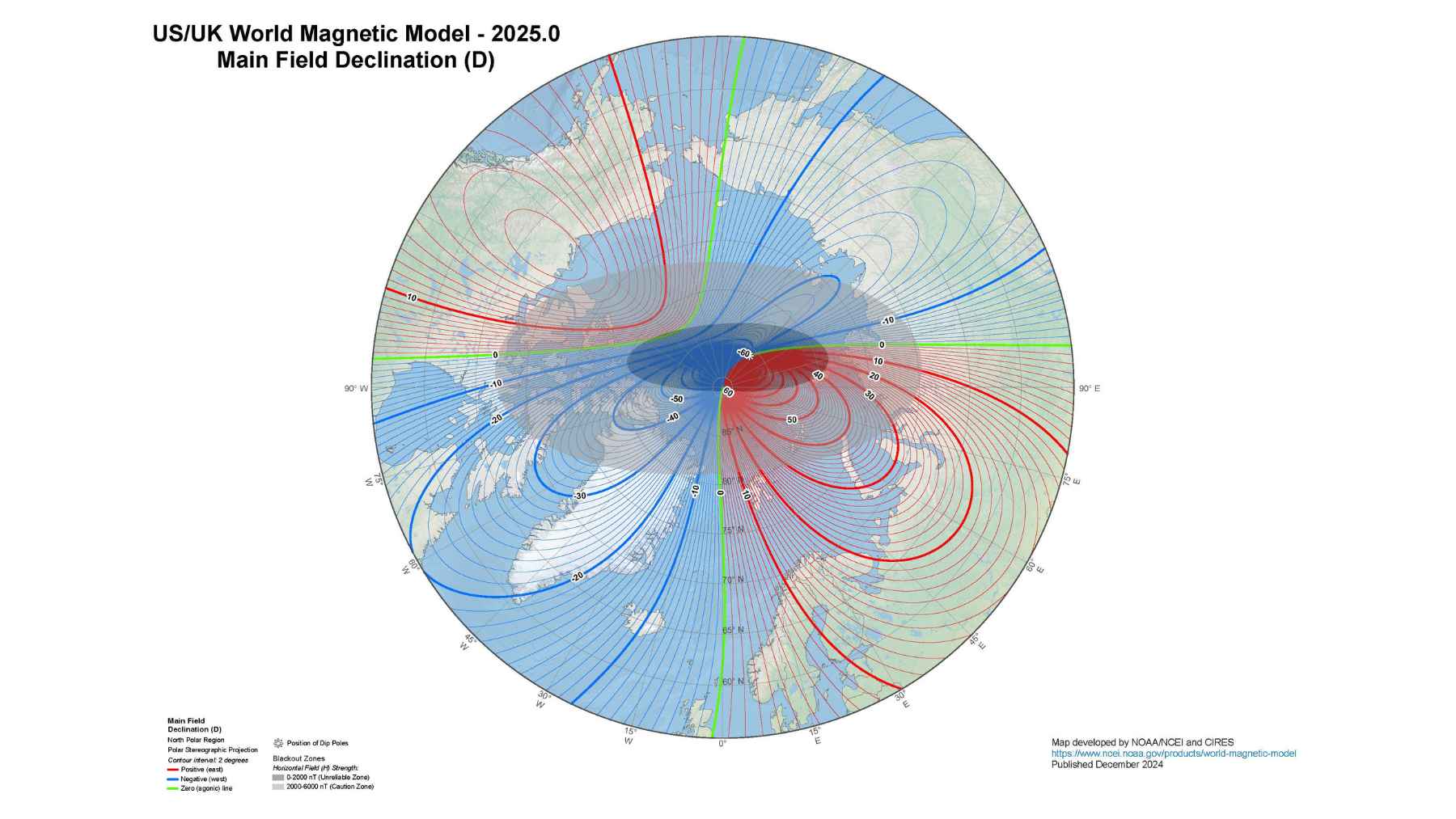

Earth’s magnetic north pole has quietly crossed an invisible line in the Arctic, leaving its long-time Canadian neighborhood and edging closer to Siberia than ever before. The latest World Magnetic Model, released at the end of 2024, now places it in a stretch of high Arctic that modern measurements have never seen it occupy.

Scientists at NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information and the British Geological Survey use this model, known as WMM2025, to track the pole’s drift. Their calculations feed directly into navigation software for planes, ships, submarines, and even the compass inside your smartphone.

What Magnetic North Really Is

For most of us, north is simply the top of a map or the direction a hiking compass points. Geographers call that fixed spot the geographic North Pole. Magnetic north is different, because it is defined by Earth’s magnetic field and marks the place where those invisible lines dive straight into the planet.

That field comes from a restless layer of molten iron in the outer core, thousands of miles beneath our feet, that behaves like a slow moving metal ocean. As this conducting fluid swirls, it generates electric currents and a self-sustaining magnetic field that shifts in complex, partly chaotic ways, so scientists rely on constant measurements and updated models.

A Pole On The Move Toward Siberia

When Arctic explorer James Clark Ross first measured magnetic north in 1831, it sat in the Canadian Arctic archipelago. Since then it has crept roughly 1,500 miles north and east toward Siberia, with its speed in the 2000s reaching about 30 miles, roughly 50 kilometers, per year.

Recent analyses show that the pole has slowed to around 20 miles each year, close to 35 kilometers, yet it is still racing by geological standards and is now closer to Siberia than to Canada. The current World Magnetic Model puts it within a few hundred miles of the geographic pole, over the central Arctic Ocean in territory it has not occupied in centuries of modern records.

Why The World Magnetic Model Matters

The World Magnetic Model turns this wandering behavior into a practical tool, giving precise values for the magnetic field at any point on Earth. It is the official reference used by US and UK defense agencies, NATO, and the International Hydrographic Organization, and the WMM2025 edition is intended to stay reliable through the end of 2029.

Airlines depend on the model to set headings for high-latitude routes, while ships, submarines, and drilling crews use its magnetic declination values to keep their courses true when GPS is weak or unavailable. The new release also adds a higher resolution companion calledWMM High Resolution 2025 and refined warning zones near the poles where the magnetic field is considered unreliable for accurate navigation.

What It Means For Daily Life And For The Future

For the most part, people will not feel this shift as they scroll around a maps app or line up a hiking compass in the backyard.

The changes that matter to pilots and navigation engineers are measured in fractions of a degree each year, and software updates based on the World Magnetic Model can quietly correct for those drifts long before they would send a plane or ship off course.

Experts who work with the 2025 model say that although the field has weakened by almost ten percent over the last two centuries and continues to evolve, there is no sign that a full magnetic pole reversal, where north and south swap places, is close, and any such flip would unfold over thousands of years rather than within a single human lifetime.

At the end of the day, the drifting pole is a reminder that our planet’s metallic core is constantly in motion, even while our phones and flight plans act as if north is fixed. The official press release was published on “NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information”.

Image credit: ESA