For most of us, a day feels like one of the few fixed things in life. 24 hours to get the kids to school, answer emails, cook dinner, maybe glance at the Moon on the way home. Yet from a planetary point of view, that 24-hour day is slipping, very slowly, out of date.

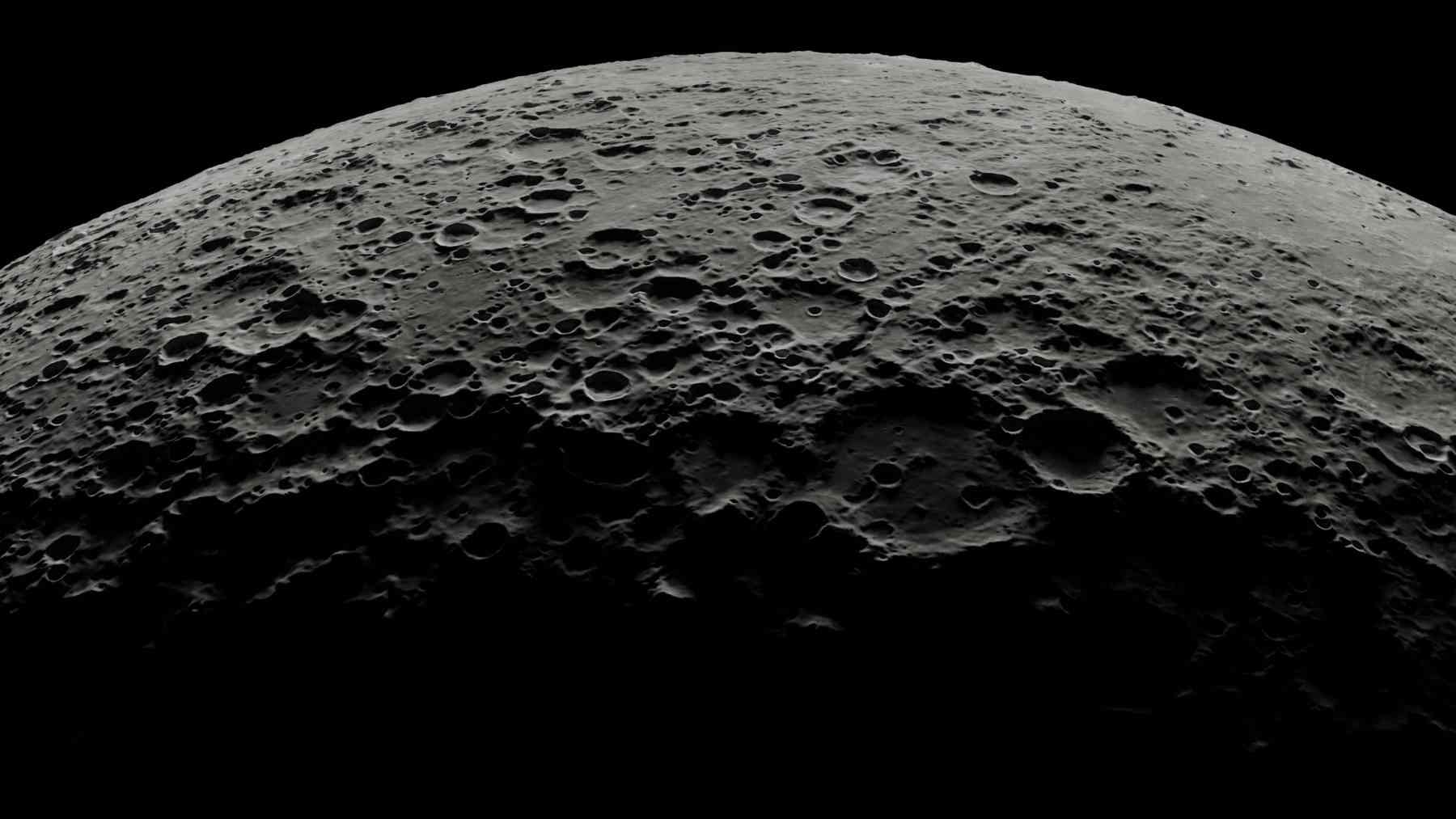

Because the Moon is drifting away from Earth by a few centimeters every year, our planet’s rotation is gently slowing down, our days are lengthening, and the tides that shape coasts and marine life are changing over geological time.

It sounds dramatic. In practice, it is a story written in millimeters and milliseconds.

A fossil clock from the age of dinosaurs

How do we even know that Earth once spun faster than it does today?

In 2020, a team of researchers turned to an unlikely timekeeper, the fossil shell of a Cretaceous bivalve called Torreites sanchezi, which lived in warm shallow seas about seventy million years ago.

Much like tree rings, this mollusk laid down fine growth bands every day as it built its shell. By using lasers to read those microscopic layers, scientists could count both daily and seasonal cycles preserved in the fossil. The pattern revealed something striking.

At the end of the dinosaur era, a year contained about 372 days, not the 365 we know now. That means each day lasted around 23.5 hours.

The only way to squeeze more days into the same year is for the planet to spin faster. A faster spinning Earth also implies that the Moon was closer, exerting a stronger pull on the oceans and on the planet’s rotation itself. The fossil shell, in other words, doubles as a tiny record of the long-term Earth Moon relationship and the marine ecosystem it lived in.

Tidal friction and a slow-motion energy trade

So why is the Moon leaving, and why does that stretch our days?

As Earth spins, the Moon’s gravity raises two tidal bulges in the oceans. Because Earth rotates more quickly than the Moon orbits, those bulges are carried slightly ahead of the line that connects both bodies. That offset matters.

The bulges tug on the Moon and give it a little forward pull. At the same time, friction between tides and the seafloor drags on Earth and robs it of rotational energy. This tidal friction transfers angular momentum to the Moon, which climbs to a slightly higher orbit while our rotation slows.

Lunar laser ranging experiments, using reflectors left by Apollo astronauts, now measure this retreat at about 3.8 centimeters per year, roughly the rate at which your fingernails grow.

On human timescales,the effect on the length of the day is tiny. Atomic clocks show that the average day is growing by about one to two milliseconds per century. You will never notice that when you hit the snooze button. Overhundreds of millions of years, though, the change adds up.

What changing days mean for tides and life

For coastal ecosystems, tides are more than a pretty backdrop. They control how often salt marshes drain, how long mudflats stay exposed for shorebirds, and how nutrients are mixed into the sea.

A stronger tidal pull in the deep past probably meant more energetic tides, different coastal erosion patterns, and slightly different habitats for early marine life. Geological records of ancient tidal deposits support the idea that days were shorter and tides different hundreds of millions of years ago.

Looking ahead, a farther Moon should slowly weaken tides and stretch days further. Some models suggest that if nothing else changed for tens of billions of years, Earth and the Moon could eventually reach a state where one side of Earth always faced the Moon.

In practical terms, though, that far future is more science thought experiment than forecast. Long before any perfect tidal lock could set in, the Sun’s increasing brightness is expected to evaporate the oceans in about one billion years, shutting down the very tides that drive lunar recession.

So for the most part, the environmental impacts that matter for coasts in our lifetimes come from greenhouse gas emissions, sea level rise, and coastal development, not from the slow drift of the Moon.

A moving Moon, a living planet

There is a quieter lesson here. The Moon’s retreat acts like a cosmic metronome, recording the passage of deep time in fossil shells and tidal rocks. It reminds us that even the things we treat as absolute, such as a 24-hour day, are products of physics and history, not fixed rules of nature.

At the end of the day, the same tidal forces that nudge the Moon away also keep Earth’s tilt relatively stable, which helps maintain a climate where complex life can evolve. The system is not perfectly balanced, just stable enough for forests, coral reefs, and yes, alarm clocks and traffic jams.

The big picture is reassuring. The Moon will keep drifting, days will keep stretching, but those changes unfold so slowly that they mainly help scientists reconstruct Earth’s past and future. For the climate and oceans we actually pass on to our children, the urgent levers are still here on Earth in our energy systems, emissions, and choices.

The study was published in the journal Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology.