Think about the last time you took a wrong turn in a familiar neighborhood and felt that sudden jolt of confusion. Your brain somehow knows when the world around you stops matching your internal map, and it reacts fast.

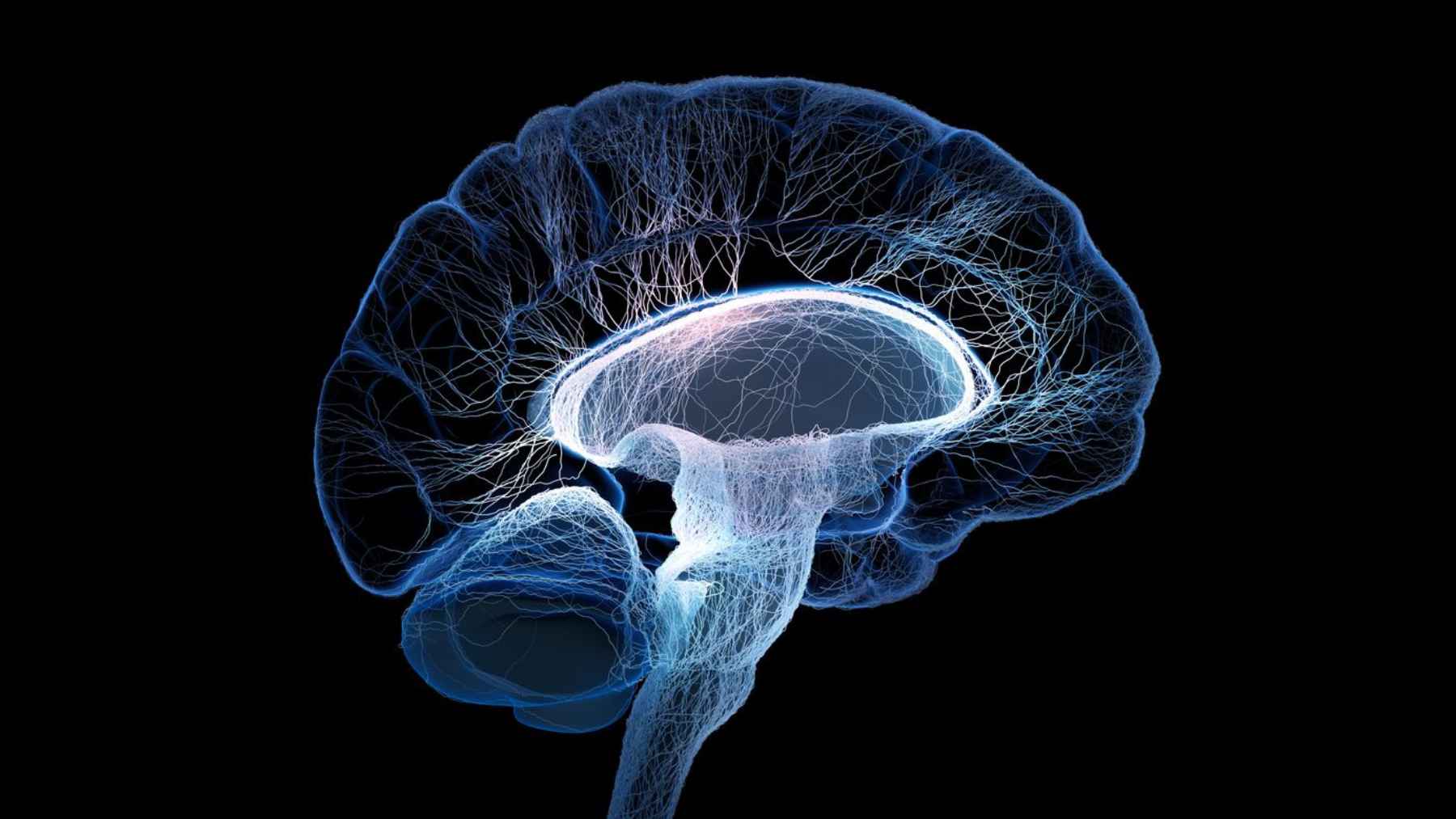

A new study using ultra-high-field brain scans and virtual reality suggests this feeling comes from a kind of navigation switch deep inside the brain that slides between “new” and “familiar” space. The work, published in Nature Communications, also hints at why getting lost is often one of the first warning signs of Alzheimer’s disease.

How your internal GPS decides what feels familiar

The team, led by neuroscientist Jörn A Quent at Fudan University in Shanghai, focused on the hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped structure that supports memory and navigation.

This region contains place cells, neurons that fire in specific locations and help build what scientists call cognitive maps of space. Earlier work suggested that one end of the hippocampus handles broad, zoomed out maps while the other handles fine, detailed locations.

In the new study, Quent and senior author Deniz Vatansever showed that the same long structure also carries a gradient for novelty and familiarity. Activity toward the front tip of the hippocampus ramped up when volunteers moved through sectors of the virtual world they had already explored many times.

The back part responded more strongly when they entered new territory, like a dial turning toward “this is different now”.

Instead of sharply dividing the brain into separate zones for new and old places, the researchers saw a continuous shift along the length of the hippocampus. To a large extent, that helps reconcile earlier studies that seemed to disagree about which regions care most about novelty. Those apparently conflicting results may simply have been looking at different points along the same sliding scale.

A virtual world built to test the navigation switch

To capture this sliding scale in action, the team asked 56 healthy volunteers aged 20 to 37 to lie in an MRI scanner while exploring a virtual landscape. On the screen, participants saw a wide grassy field ringed by distant mountains and had to steer around to collect six objects scattered across the space. The setup resembled a minimalist open-world video game, only with a very real humming scanner around their heads.

The brain activity was recorded with seven Tesla functional MRI, a very powerful imaging method that tracks changes in blood flow as a stand-in for neural activity. At the same time, the researchers logged exactly where each person moved, how often they visited each sector of the landscape, and how long it had been since they were last there.

From this, they calculated a novelty score for every patch of space and sorted those scores into six levels, from highly new to very familiar.

When volunteers entered the most novel areas, they tended to slow down, pause, and rotate more, behavior that suggests they were paying extra attention to new details. Across the brain, visual and frontoparietal regions lit up for these fresh locations, networks usually linked to perception and focused control of attention.

More familiar routes leaned on motor and default mode networks that support well-learned movements and memory, the mental equivalent of walking home on autopilot after a long day.

Why this matters for Alzheimer’s and everyday life

The hippocampus and nearby posterior medial cortex, which also showed its own novelty to familiarity gradient, are among the first regions damaged in Alzheimer’s disease. Clinicians have long noticed that trouble finding the way, even in places someone has known for years, often appears before clear memory loss. By mapping how these regions normally encode new versus familiar spaces, the new work offers a clearer target for detecting early disruption.

In interviews about the study, Vatansever compared moving to a new city with the virtual task and noted that comfort only comes after active exploration. As he put it, “You have to explore your environment to become familiar with it.” The brain’s navigation switch seems to track that journey, gradually shifting activity as streets, landmarks, and shortcuts move from strange to known, and if that gradient fails to update, a neighborhood can feel confusing long before someone forgets a birthday or an appointment.

The findings also fit into a larger picture of the hippocampus as a flexible mapping engine for many kinds of information, not only physical space. Other research has shown that similar circuitry helps people navigate abstract social relationships, for example in a 2018 perspective on social navigation that described how power and affiliation can form a kind of mental map.

The main study was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Image credit: University of Liège