Did one of history’s most famous inventions quietly create the superstar material of modern clean tech more than a century ahead of its time?

A new materials science study suggests that the carbon filaments inside Thomas Edison’s 1879 light bulbs may have briefly turned into graphene, long before anyone knew such a material existed.

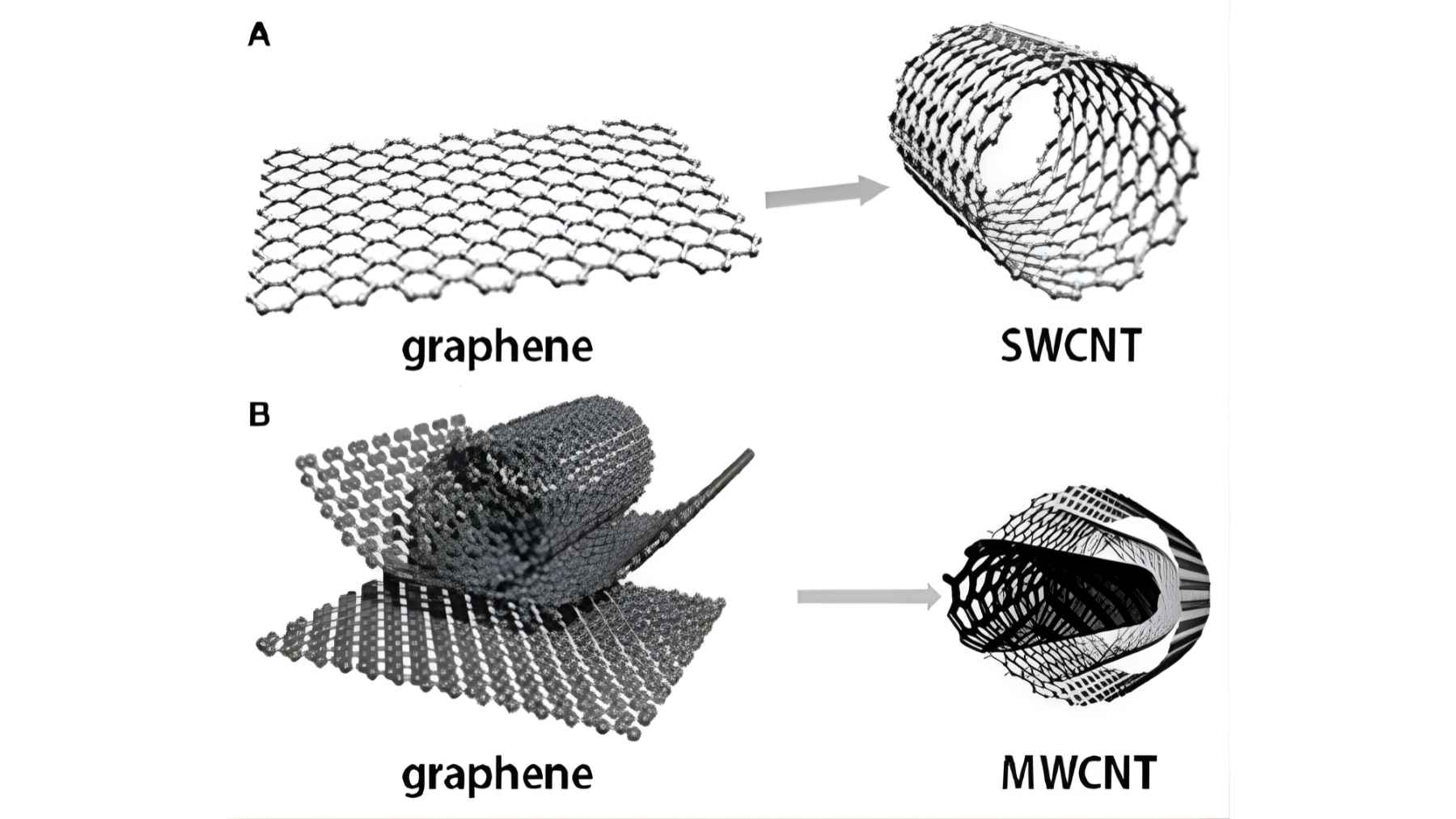

Graphene is a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a honeycomb pattern. It is incredibly strong, light, and an excellent conductor of electricity, which is why researchers see it as a key ingredient for better batteries, supercapacitors, flexible electronics, and lighter composite materials that can reduce energy use.

Recreating a 19th century light bulb

The new work comes from researchers at Rice University, led by chemist James Tour. They set out to rebuild Edison-style bulbs as faithfully as possible, using the 1879 patent as a blueprint and sourcing artisan lamps with carbon-based filaments made from Japanese bamboo, just a few micrometers thicker than the originals.

Graduate researcher Lucas Eddy wired these replica bulbs to a 110 volt direct current supply, the kind of setup Edison himself would have used. The team switched the bulbs on for only about twenty seconds at a time, since longer runs tend to transform carbon into ordinary graphite rather than the more exotic graphene structure they were hoping to see.

Under an optical microscope, the filament surface changed from dark gray to a bright metallic sheen, a first hint that something unusual had happened. Using Raman spectroscopy, a laser-based technique that reads the atomic “fingerprints” of materials, the researchers detected the signature of turbostratic graphene in specific regions of the carbon filament.

Turbostratic graphene is made of multiple graphene layers stacked slightly askew, more like a shuffled deck of cards than a perfectly aligned pile. That misalignment makes the layers easier to separate and mix into other materials, which is very attractive for large-scale energy storage devices and reinforced composites.

From flash heating to clean tech

To a large extent, Edison’s bulb seems to have created a 19th century version of a modern technique known as flash Joule heating. In that process, a short, intense electrical pulse heats carbon-based feedstocks to roughly two to three thousand degrees Celsius, converting them into turbostratic graphene in a fraction of a second.

Tour’s lab has already shown that flash Joule heating can turn waste food, plastic, and even coal into turbostratic graphene, with promising applications in low-carbon concrete, lighter composites, and improved energy storage.

In practical terms, that means yesterday’s trash or industrial byproducts could become additives that strengthen materials while trimming their climate footprint.

So did Edison really “invent” graphene? The researchers are careful on that point. They cannot test original museum filaments, and long burn times like the famous multi-hour bulb tests probably pushed the material toward graphite.

The new work instead shows that the electrical and thermal conditions inside those early carbon lamps were capable of producing graphene for at least short periods.

“To reproduce what Thomas Edison did, with the tools and knowledge we have now, is very exciting,” Tour said, noting that the finding raises fresh questions about what other advanced phenomena might be hiding in old experiments.

Why this old bulb matters for the future

For most households, the incandescent bulb is now a nostalgic object, replaced by efficient LEDs that cut both the electric bill and emissions. Yet this study shows that the same humble technology once powered by coal fired grids can also guide the next generation of cleaner materials, from graphene-enhanced batteries to stronger, lighter structures that use fewer resources.

At the end of the day, the message is simple. Revisiting classic experiments with modern tools does not only rewrite scientific history, it can also uncover low-cost routes to materials that support a more sustainable economy.

The scientific study was published in ACS Nano.