For more than a century, the supergiant amphipod Alicella gigantea has been treated almost like a deep-sea legend. A pale, shrimp-like crustacean the length of a laptop, glimpsed only in a handful of trawl nets and trench expeditions. Now a new global study shows that this supposed rarity actually occupies about 59 percent of the world’s seafloor, quietly thriving in some of the harshest places on Earth.

At first glance, that sounds like trivia from the very bottom of the ocean. It is not. The work, led by Dr. Paige J. Maroni at the University of Western Australia (UWA) and published in Royal Society Open Science in May 2025, pulls together 195 records from 75 locations in the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans.

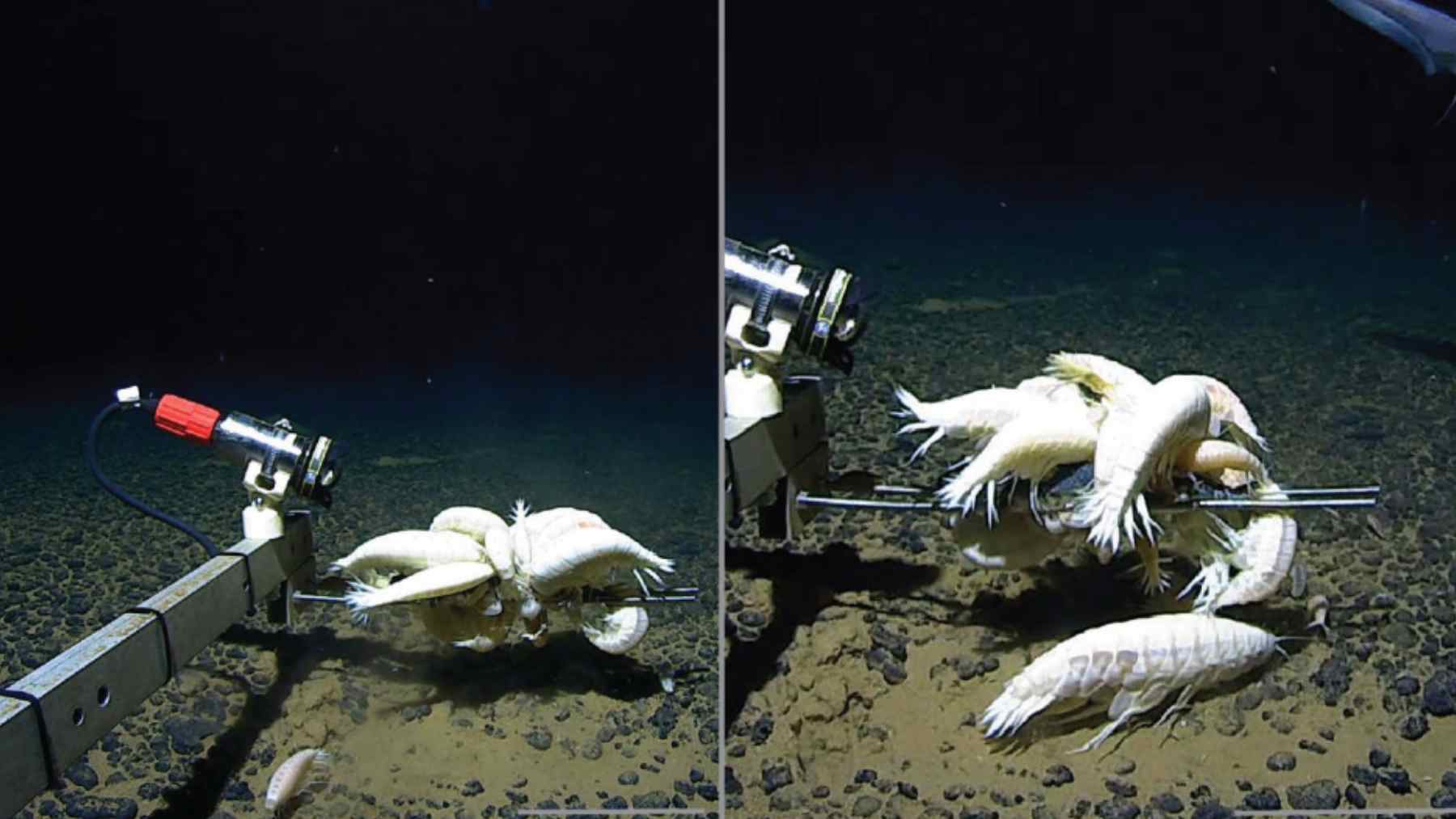

By combining deep-sea camera footage, baited landers, and genetic data, the team concludes that A. gigantea is widely distributed across lower abyssal and upper hadal zones between roughly 3,890 and 8,931 meters. In other words, this animal is a regular resident of vast plains and trenches that cover more than half of the global seabed.

Alicella gigantea and deep-sea life

So what exactly is this creature that turns up where sunlight never does? Alicella gigantea is the world’s largest known amphipod, a type of crustacean related to the tiny “sand hoppers” you might see at the beach. Some individuals reach about 34 centimeters in length, an extreme example of the so-called abyssal gigantism seen in several deep-sea animals.

Its body is mostly white, its shell thin, and its lifestyle largely scavenging on carrion that sinks from the surface. That diet helps move carbon from dead organisms into the deep seabed, one small part of the ocean’s vast carbon-cycling engine.

Deep-sea sampling bias and new technology

For decades, scientists thought this giant was genuinely scarce. Specimens appeared in nets only occasionally, and there were just seven DNA-based studies before this project. “Historically, it has been sampled or observed infrequently relative to other deep-sea amphipods, which suggested low population densities,” Maroni explained in a university statement.

The new study flips that story. Instead of being rare, A. gigantea looks to be a low-profile cosmopolitan, spread across nine trenches and multiple fracture zones yet often missed by traditional sampling gear.

Genetics and global connectivity in the abyss

The genetics are just as surprising. Researchers sequenced two mitochondrial genes and one nuclear gene from amphipods collected around the world. They found very little genetic differentiation among far-flung populations, with many individuals sharing the same haplotypes.

That pattern suggests strong connectivity across the deep ocean, possibly helped by past shifts in currents and tectonic changes over millions of years. In practical terms, it means a single supergiant species may be linking food webs from the North Pacific trenches to the basins of the South Atlantic.

Deep-sea mining risks and seabed biodiversity

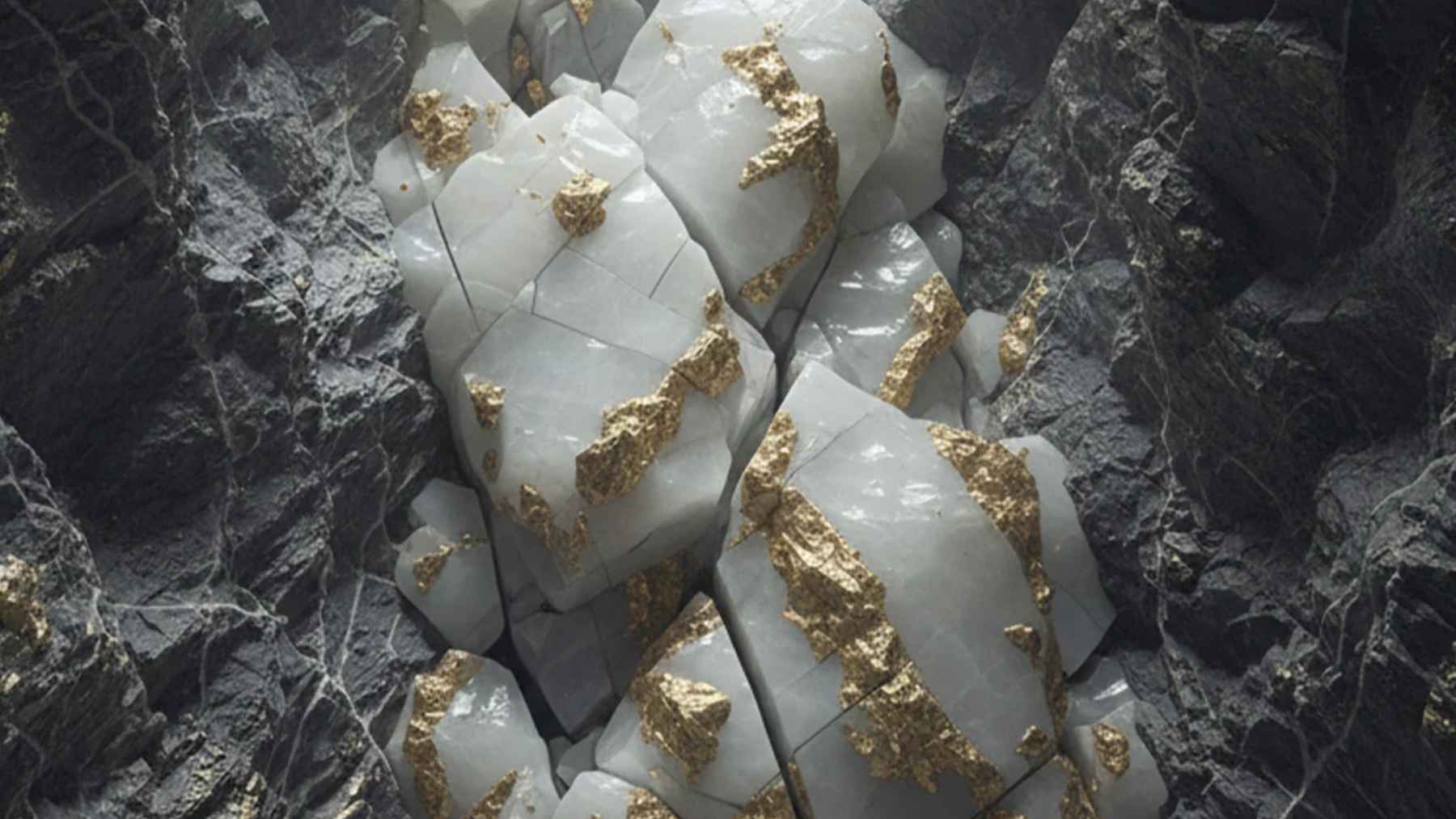

Why does this matter beyond the world of trench specialists and submarine pilots? Because A. gigantea lives exactly where industrial pressures are now growing. Abyssal plains and nearby fracture zones are prime targets for future mining of polymetallic nodules and other mineral deposits.

Studies show that experimental disturbances in these environments can depress carbon flow and biodiversity for decades, with some communities still altered more than twenty-six years after a small-scale test.

Carbon cycling and how little of the deep ocean we have seen

At the same time, the deep sea as a whole is doing heavy lifting for the climate we experience at the surface. Regions below 200 meters account for more than 90 percent of the ocean’s volume and absorb the majority of excess heat and around 30 percent of human-generated carbon dioxide.

Yet a recent analysis estimates that less than 0.001 percent of the deep seafloor has been visually explored, an area about the size of Rhode Island. In that context, mistaking a widespread scavenger for a near-mythical oddity is more than a catalog error. It shows how thin our baseline really is.

Maroni points to the technological shift behind the new picture. Modern baited landers, high-definition cameras, and next-generation DNA sequencing are revealing animals that older gear simply missed. “As exploration of the deep sea increases to depths beyond most conventional sampling, there is an ever-growing body of evidence to show that the world’s largest deep-sea crustacean is far from rare,” she said.

For policymakers debating deep-sea mining rules, this kind of result is a warning light. If a thirty-centimeter crustacean can hide in plain sight across more than half of the ocean floor until 2025, what else is out there that we have not even named yet.

Scientists and international bodies already argue that large-scale extraction should wait until we understand these ecosystems well enough to avoid “serious harm” and irreversible biodiversity loss.

Down at the level of everyday choices, it is easy to forget that while we worry about traffic, grocery prices, or the next electric bill, slow-growing communities in the abyss are processing our waste carbon and stabilizing the planet’s climate. Alicella gigantea is not a mascot that will ever show up on a reusable coffee cup. Most of us will never see one outside a research photo.

Yet this hidden giant offers a simple reminder. Before we scrape and mine the deep seafloor for short-term gains, we are still learning who lives there.

The study was published on the Royal Society Open Science website.