A lobster dropped into a pot of boiling water is one of those kitchen images that most people either accept without thinking or avoid entirely. Now a new study is giving that debate a sharper scientific edge by recording live nerve activity inside a crab’s central nervous system while researchers applied potentially harmful stimuli

The work does not “prove” a crab feels pain the way humans do, but it does strengthen the case that these animals detect tissue damage in more complex ways than a simple reflex.

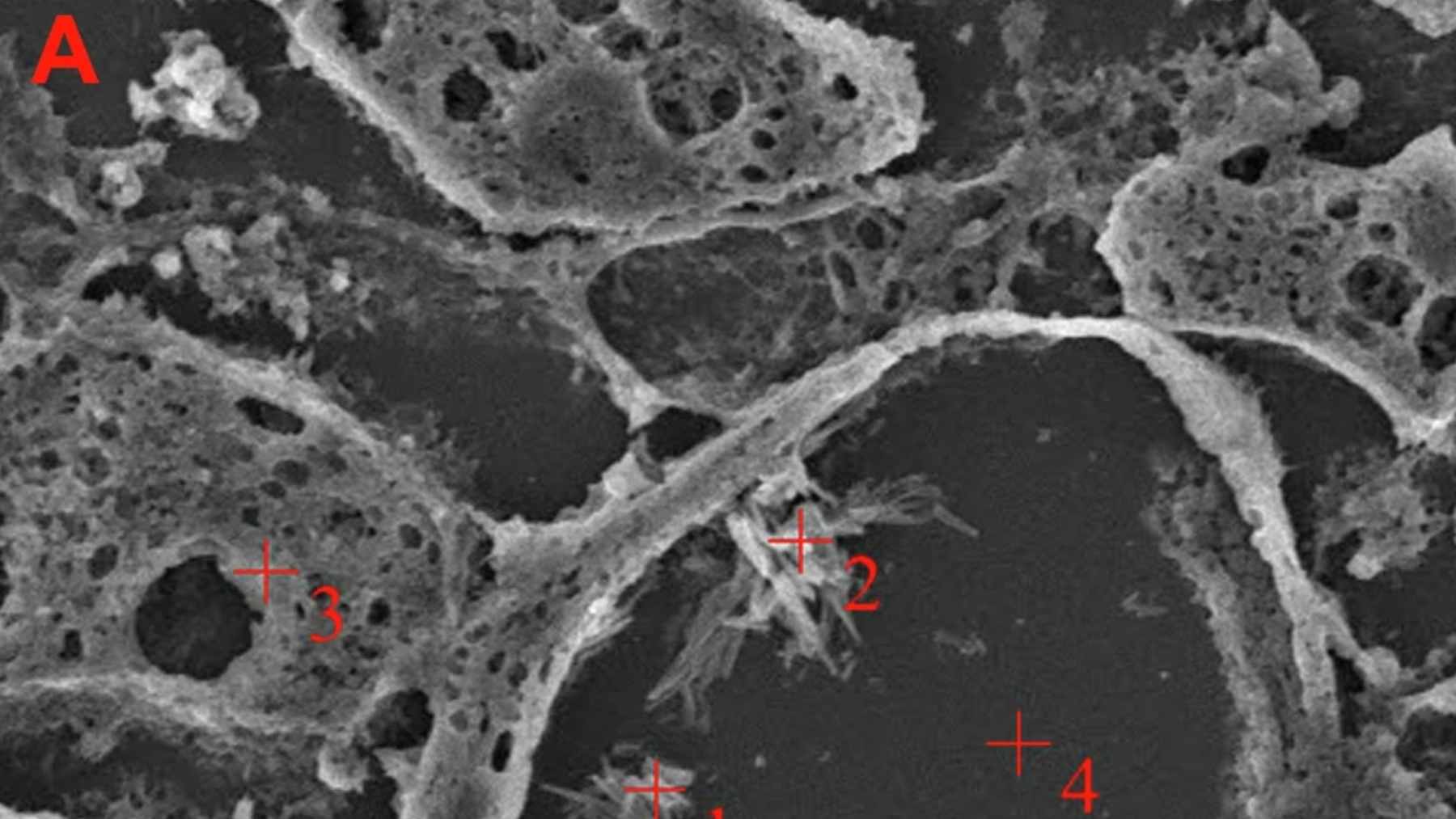

The research, published in Biology, focused on the European shore crab (Carcinus maenas). A team led by Eleftherios Kasiouras and colleagues used in vivo electrophysiology, meaning they recorded neural activity in an intact, living animal rather than in isolated tissues. They applied two types of stimuli to soft tissues including joints of legs and claws, antennae-related tissues, and eyes.

One was mechanical pressure using von Frey hairs, a standard tool for applying calibrated touch. The other was acetic acid at different concentrations, a commonly used noxious chemical in pain research across many animals.

What the scientists actually measured

The key result is simple and hard to dismiss. When the researchers applied acetic acid to several body areas, they detected clear changes in neural activity in ganglia that receive sensory input from those tissues. They interpreted this as evidence of “putative nociceptors,” which are receptors that detect damaging or potentially damaging stimuli.

In plain language, the crab nervous system reacted differently when something potentially harmful happened.

The study also reported a pattern that will sound familiar to anyone who has followed pain research in other animals. Mechanical stimulation produced shorter, higher-amplitude responses, while acetic acid produced longer-lasting responses with different signal characteristics. In their dataset, the differences between response duration and amplitude for chemical versus mechanical stimulation were statistically significant.

Importantly, the authors were careful with their wording. Nociception is not the same thing as the full experience of pain. Nociception is a biological alarm system. Pain, as many scientists define it, also involves an aversive emotional state and higher-level processing. This distinction matters because it is where scientific consensus still gets messy.

Nociception, pain, and a real scientific disagreement

Animal welfare arguments often jump straight from “the animal reacts” to “the animal suffers.” Some researchers think that leap is justified for decapod crustaceans based on a growing pile of behavioral and physiological evidence. Others argue we should be more cautious, especially when lawmakers are asked to regulate entire industries.

A recent review in Reviews in Fisheries Science and Aquaculture lays out “reasons to be skeptical” about sentience and pain claims in fishes and aquatic invertebrates, emphasizing how hard it is to infer subjective experience from nervous system responses alone.

The new crab electrophysiology paper does not end that debate. But it does raise the bar. It adds direct neural evidence to behavioral studies that previously relied on what animals do after a harmful event, such as rubbing, guarding a body part, or learning to avoid a location.

Laws are already moving faster than the science

Even without a universal scientific consensus, policy is shifting. The United Kingdom has moved to recognize decapod crustaceans and cephalopods within its sentience framework, following an evidence review commissioned by the government.

Switzerland went further in a practical way. Its animal protection reforms require crustaceans like lobsters to be stunned before being killed, effectively banning the classic “boil alive” method.

New Zealand’s guidance for crustacean welfare also points toward stunning as the preferred option, while discussing chilling methods used to reduce activity before killing.

Retail pressure is starting to matter too. In early 2025, the UK grocer Waitrose announced it would stop selling prawns killed by suffocation and shift toward electrical stunning across its farmed prawn supply chain.

What readers should keep in mind

If you eat crab, lobster, or shrimp, the takeaway is not that your dinner “definitely suffered.” The honest takeaway is that the nervous systems of these animals are signaling damage in measurable, structured ways, and society is increasingly treating that as ethically relevant.

As zoophysiologist Lynne Sneddon put it, “We need to find less painful ways to kill shellfish if we are to continue eating them.” That is a value statement, but it is grounded in a changing scientific record that is getting harder to ignore.