Most visitors step into Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave for cool air and quiet darkness, not for sharks. Yet high above the tourist walkways, in pale limestone ceilings and walls, scientists have uncovered the remains of two powerful marine predators that swam here roughly 325 million years ago.

The newly described species are Troglocladodus trimblei and Glikmanius careforum, both members of an extinct group called ctenacanth sharks. Their fossils were found in rock layers inside Mammoth Cave National Park and in matching formations in northern Alabama.

These animals reached about 10 to 12 feet in length, similar to a modern oceanic whitetip or lemon shark, and cruised a shallow coastal sea that once covered this part of North America.

Two predators from a vanished shoreline

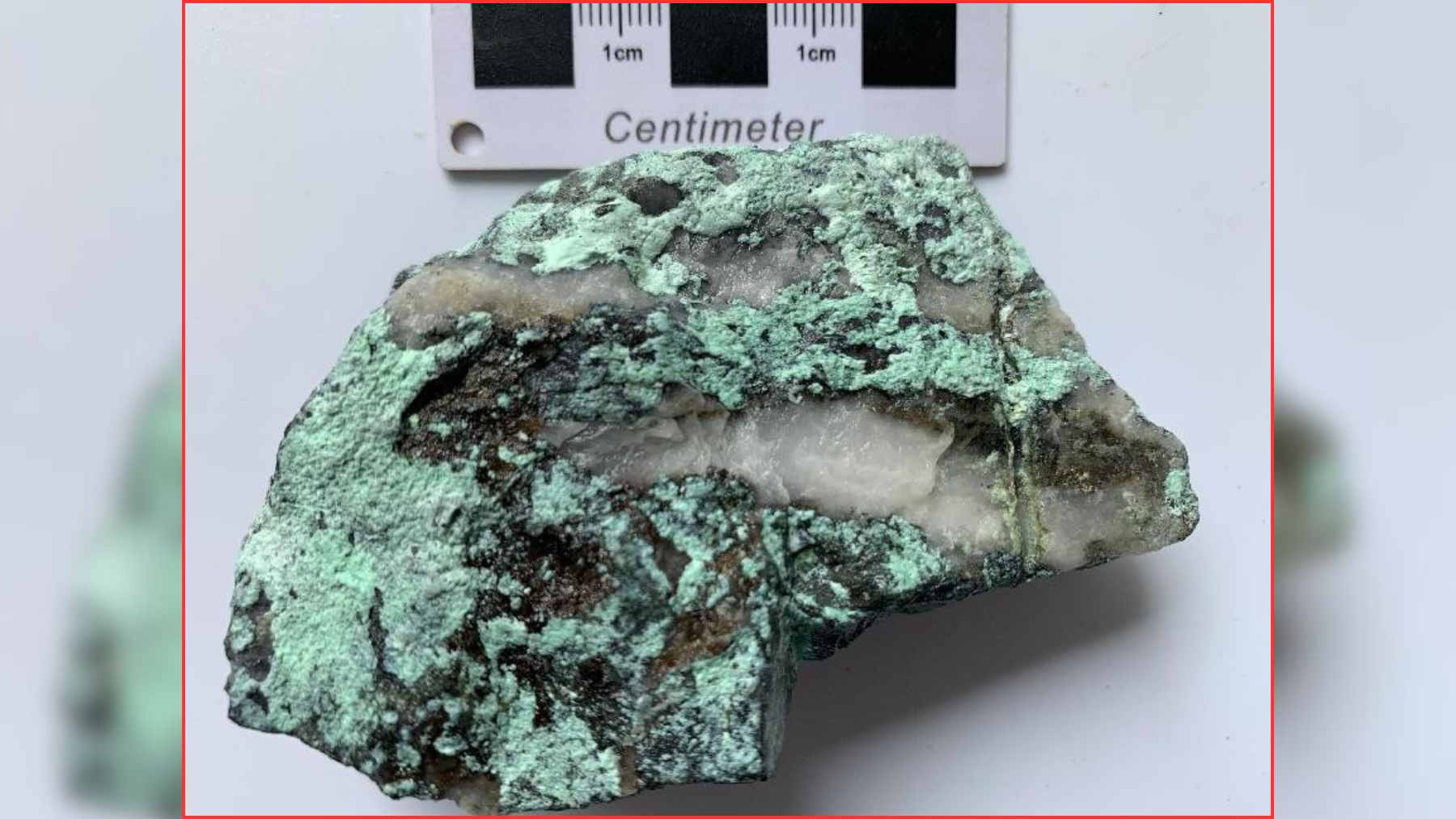

Troglocladodus trimblei is a brand new genus and species, known from adult and juvenile teeth preserved in the St. Louis and Ste. Genevieve formations at Mammoth Cave and the Bangor Limestone in Alabama. The genus name refers to its “branching” tooth shape, while the species honors park superintendent Barclay Trimble, who spotted the first tooth during a survey in 2019.

Under magnification, Troglocladodus teeth show a tall central cusp flanked by multiple smaller points, a kind of trident repeated across the jaw. That arrangement would have been ideal for gripping and slicing soft prey in coastal waters, much like some modern reef sharks do today.

Glikmanius careforum belongs to a genus that scientists already knew from other fossil sites. This new species changes the picture by appearing more than fifty million years earlier than previous records and by preserving something extremely rare in shark paleontology, a partial set of jaws and gill arches.

Its teeth are shorter and more robust than those of its relatives, and its jaw shape points to a short-headed hunter with a powerful bite that likely chomped smaller sharks, bony fish and squid-like orthocones. The species name thanks the Cave Research Foundation, whose volunteers helped find the fossil material.

A cave that remembers the sea

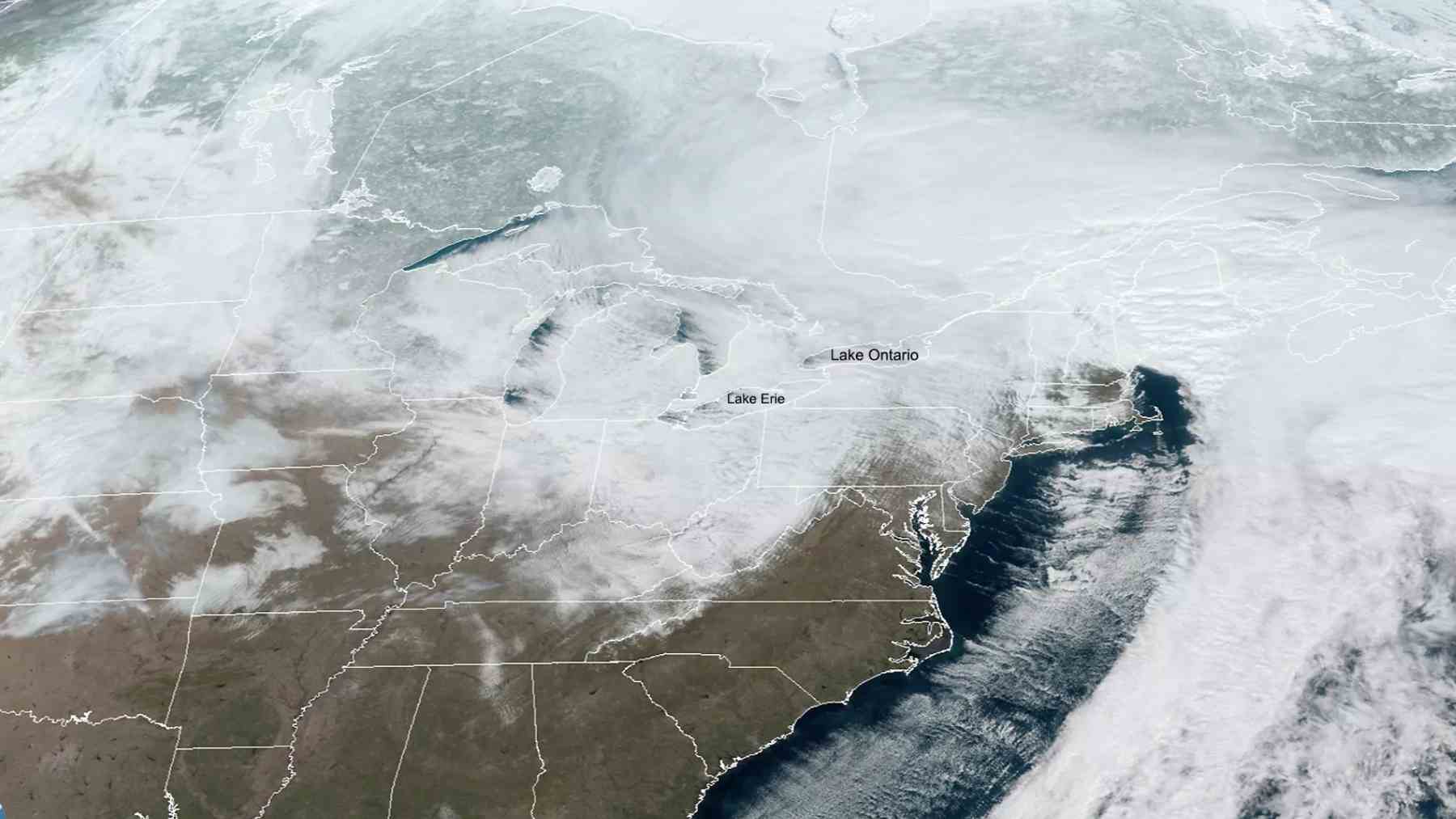

It can be hard to imagine saltwater life while you shuffle through a cool, dry passage with a tour group. The rocks tell a different story. The limestone that forms Mammoth Cave was laid down in a warm, shallow sea during the Mississippian part of the Carboniferous period. Later, as sea levels fell and continents collided to build the supercontinent Pangaea, that seaway vanished and the region slowly rose above the waves.

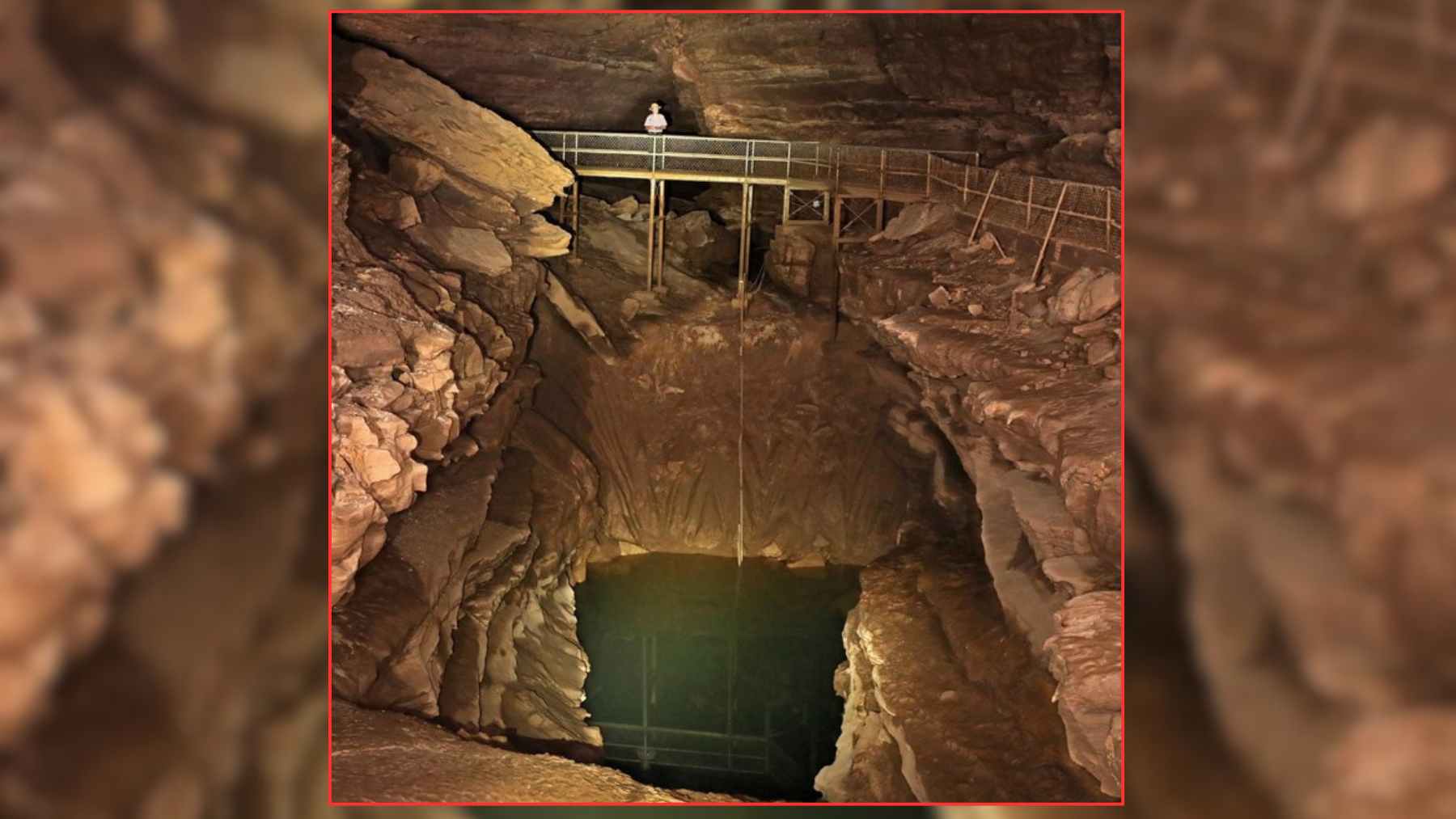

Only much later did groundwater carve the vast cave system that visitors see today. Explorers have mapped more than 426 miles of interconnected passages, making Mammoth Cave the longest-known cave system on Earth and a UNESCO World Heritage Site as well as a biosphere reserve.

Those same stable underground conditions that feel so pleasant on a sticky summer day help protect fragile fossils. Since 2019, an ongoing Paleontological Resource Inventory led by shark specialist John Paul Hodnett and the National Park Service has documented at least seventy ancient fish species from more than twenty five caves and passages in the park, most of them sharks and their relatives.

What these fossils tell us about ancient seas

For paleontologists, Troglocladodus trimblei and Glikmanius careforum are more than headline friendly “sea monsters”. Their teeth and jaw structures add key clues about how different shark lineages evolved during a time when fish diversity was booming and coastlines were shifting. The new research suggests that ctenacanth sharks formed at least three major lineages with a wide range of body sizes and feeding styles.

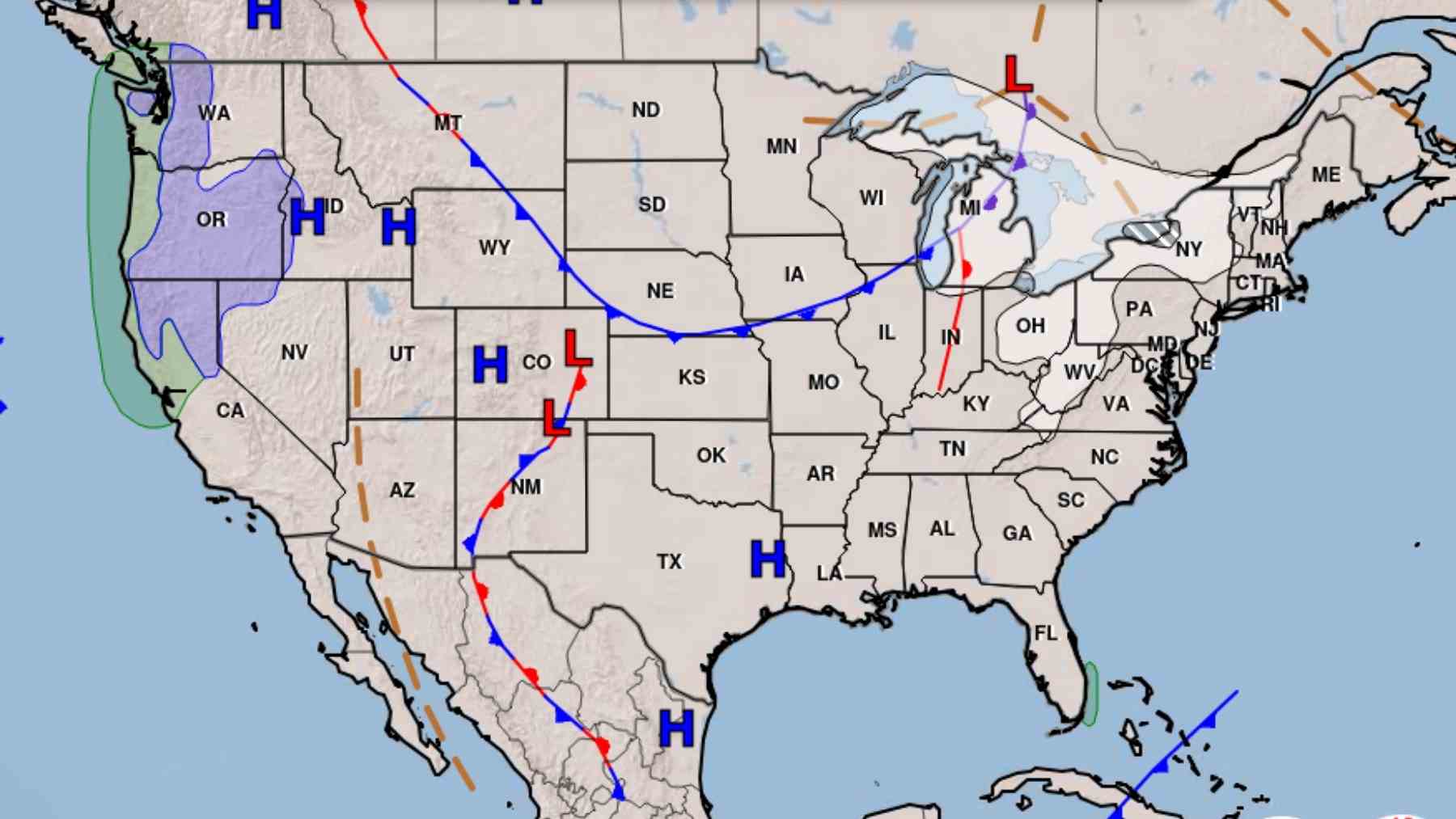

Because the same species appear in both Kentucky and Alabama, scientists can link fossil faunas across hundreds of kilometers and reconstruct an ancient seaway that once connected what is now eastern North America to parts of Europe and North Africa. That seaway supported rich near-shore ecosystems long before dinosaurs appeared, and then disappeared as continents moved together.

In practical terms, discoveries like these turn Mammoth Cave into a kind of natural archive. By comparing its fossil sharks with similar finds around the world, researchers can trace how marine ecosystems responded to large-scale changes in sea level and geography. Those long-term records do not offer simple one-to-one lessons for today’s oceans, but they do show that coastal habitats can change dramatically when the planet’s boundaries are redrawn.

Protecting a deep time treasure

Mammoth Cave is already famous with hikers and families for its underground rivers, rare cave wildlife and guided tours. Less visible is the careful work of mapping, photographing and sometimes delicately sampling fossils that cannot be replaced if damaged or removed. National park rules prohibit casual collecting, and scientists working in the cave follow strict protocols to balance research with conservation.

So the next time someone complains about the long line for cave tickets or the chilly air inside, it may be worth remembering that sharks once patrolled just above today’s ceilings. Their teeth and jaws are locked in the rock now, waiting quietly while researchers piece together the story of an ancient sea.

The study was published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.