Far off the New England coast, one of Earth’s rarest whales is surviving on clouds of plankton that most of us never notice. Now scientists can see those tiny red creatures from hundreds of miles above the ocean, opening a new way to track the North Atlantic right whale. Only around 370 of these giants are thought to remain worldwide.

The key is a rice-sized crustacean called Calanus finmarchicus. Packed with energy-rich fat, these copepods form a high-calorie buffet that fuels whales, fish, and seabirds in the Gulf of Maine and northern waters. If Calanus were to disappear from these feeding grounds, scientists warn that every predator higher up the food chain would feel the loss.

A tiny red crustacean with outsized importance

How do you find something smaller than a grain of rice in an ocean that covers most of our planet? For Calanus, the answer lies in its own color. Each animal carries a reddish pigment called astaxanthin. When huge numbers rise toward the surface, that pigment absorbs blue-green light and slightly changes how the ocean reflects sunlight back into space.

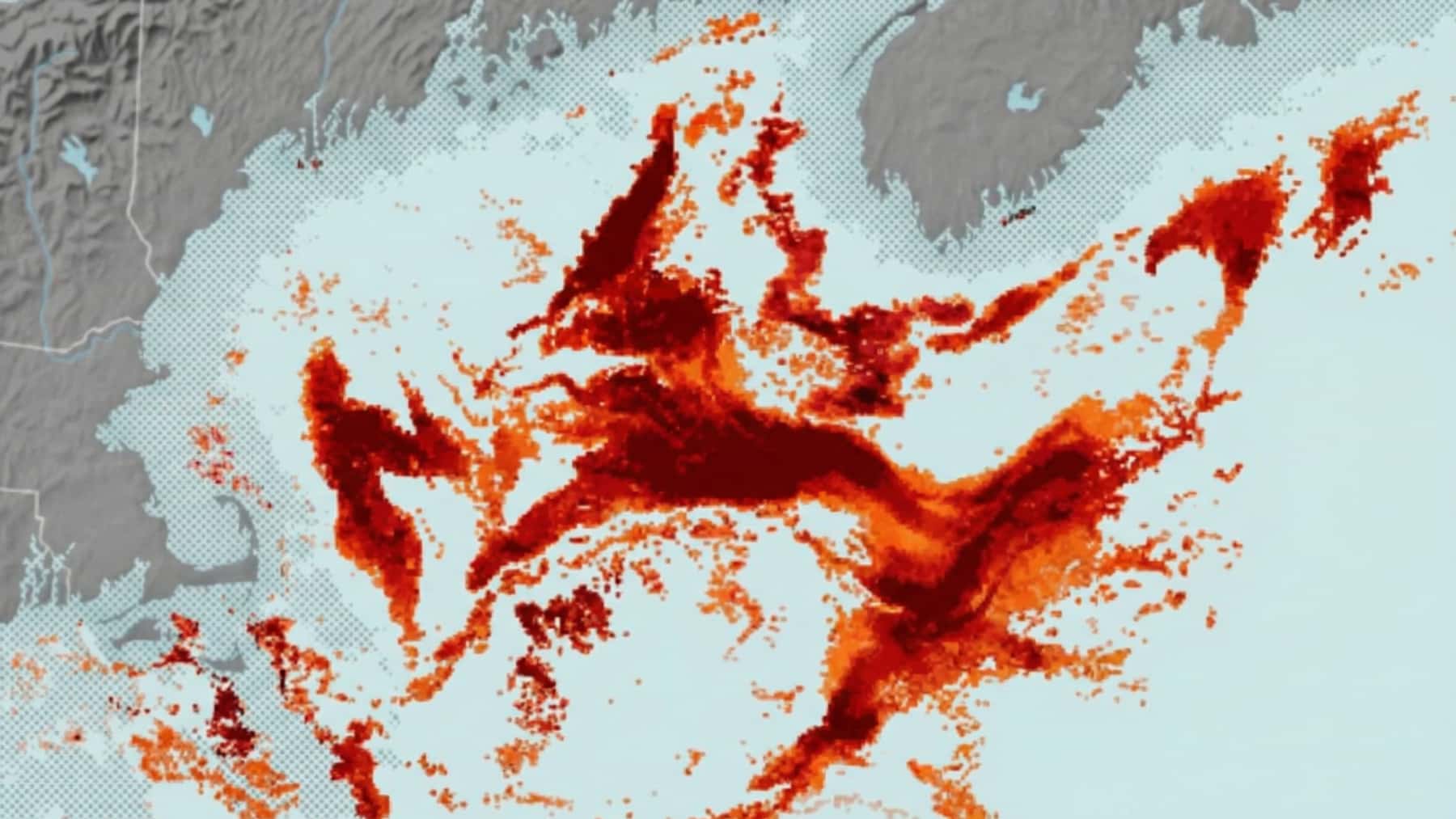

Turning ocean color into a plankton map

To pick up that color shift, researchers used the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer on board NASA’s Aqua satellite. The instrument measures how different wavelengths of light bounce off the sea surface, which depends on what is in the upper layer of the water. Where Calanus are especially thick, the water looks just a bit redder than computer models predict for an ocean without them.

The team processed those measurements into enhanced color maps that highlighted unusual red patches. One image showed a swarm of roughly 150,000 Calanus in each cubic meter of water. Earlier tests in the Norwegian Sea showed that swarms can be large enough to alter ocean color across whole regions. Ship-based sampling with a Continuous Plankton Recorder, towed behind research vessels, helped confirm that the red patches really matched dense plankton swarms.

Following the food trail to protect whales

Right whales go where Calanus is most abundant. When dense swarms sit in traditional feeding spots, the whales tend to stay in areas that researchers and regulators know well. When those swarms shift, the whales follow, often crossing busy shipping lanes or fishing grounds where lines and nets are in the water. Ship strikes and entanglement in fishing gear remain two of the most serious human-related threats to the species.

Being able to map Calanus from space could, over time, help managers anticipate where whales are likely to turn up before they are spotted at the surface. That information could support temporary speed limits for large vessels, short-term fishing closures, or small adjustments to heavily used routes when whale food and shipping traffic overlap. Canada already uses seasonal speed restrictions in some right whale habitats, and similar rules are under debate in United States waters.

From early-stage science to everyday decisions

For now, this plankton mapping is still an early tool. It works best when the ocean is clear and when the copepods gather near the surface. The current system depends on the aging MODIS sensor. Future missions such as NASA’s PACE satellite, which measures hundreds of colors of reflected light, should make it easier to separate red zooplankton swarms from muddy water or algal blooms near the coast.

Even with those limits, the approach points to a new way to connect space technology with ocean decisions that affect daily life. Cargo ships that bring goods to ports, fishing boats, and whale watching tours all share the same crowded coastal waters. If scientists refine this view of the whales’ food supply, authorities will have a better chance of steering human activity away from the last remaining right whales before disaster strikes.

At the end of the day, a microscopic red speck in the water could become one of the most important signals for saving a 40-ton animal. That is a reminder that in the ocean, as in much of nature, the smallest players often hold up the biggest lives.

The study was published on “Frontiers in Marine Science”.