Most of us know magnetism from everyday life, like fridge magnets or the tiny motors buzzing inside a laptop fan. For a long time, physics textbooks said there were two main magnetic families running that show.

Now researchers have not only confirmed a third kind of magnetism but have also learned how to shape it on tiny chips.

In a new experiment, a team led by scientists at University of Nottingham used intense X-rays in Sweden to image and control this new behavior in an ultrathin layer of manganese telluride, work that appears in the journal Nature and could one day change how digital devices store and move information.

What exactly is this new kind of magnetism?

To understand why this matters, it helps to rewind to the basics. In a simple picture, each electron acts like a tiny bar magnet with a property called spin that points either up or down. In familiar ferromagnets such as the metal on your refrigerator door, many spins line up in the same direction so the material creates a strong magnetic field you can feel.

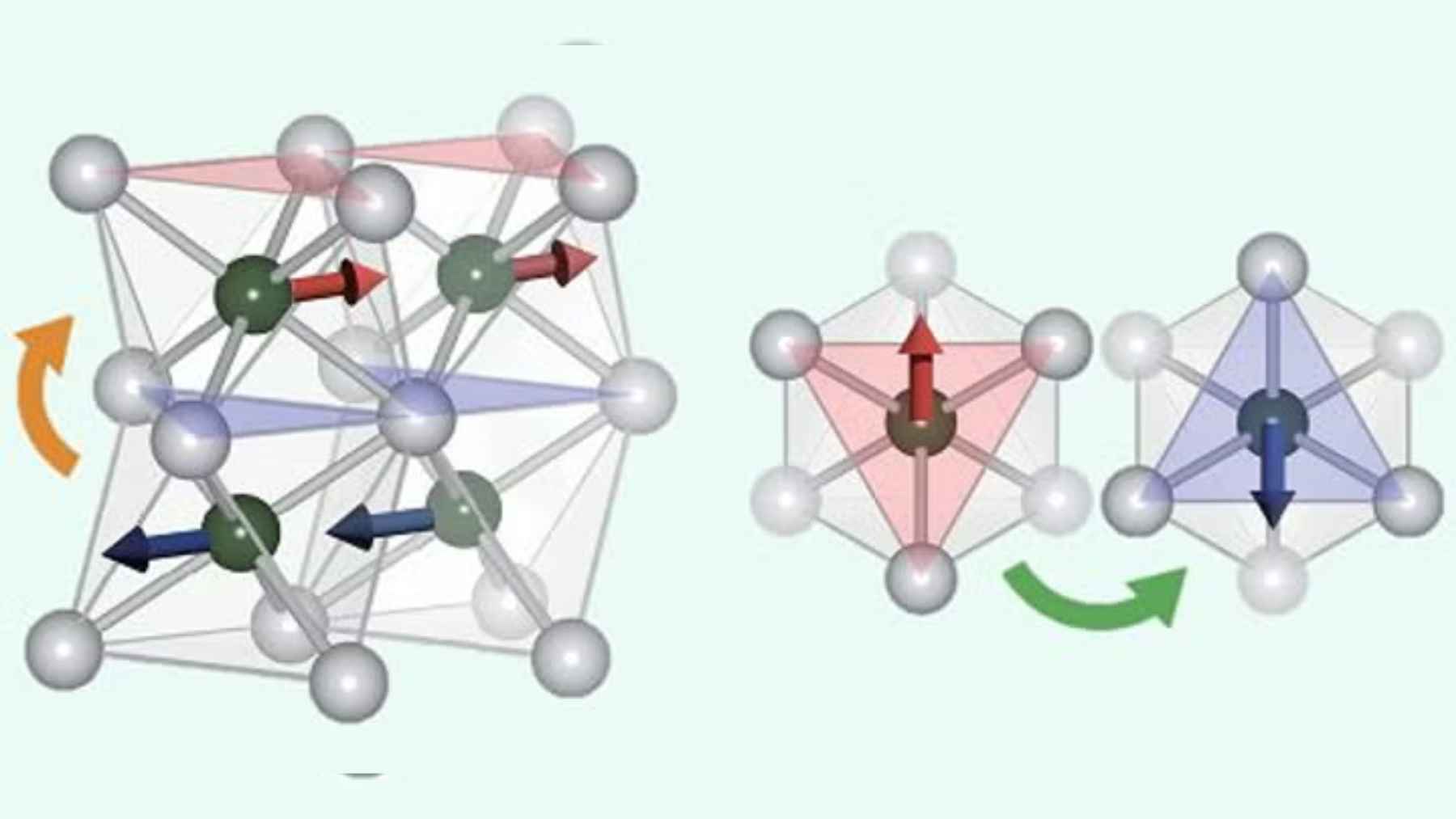

In antiferromagnets, neighboring spins point in opposite directions and mostly cancel one another, so the material looks nonmagnetic from a distance even though plenty is happening inside.

About five years ago, theorists proposed a third option named altermagnetism, where spins still alternate but the crystal structure twists their arrangement in a way that gives electrons strong internal cues while the overall magnet looks almost perfectly balanced.

Inside the Swedish experiment on ultrathin manganese telluride

In the new study, the team grew a film of manganese telluride only a few dozen nanometers thick, thousands of times thinner than a sheet of paper. They then carved it into tiny geometric devices so that the internal magnetic pattern would respond to the shapes, a bit like how city streets guide the flow of traffic.

To see what the spins were doing, the researchers brought their samples to the MAX IV Laboratory in Sweden, a synchrotron that accelerates electrons around a ring and produces extremely bright X-rays.

By tuning the X-rays and watching how electrons popped off the surface, they built detailed maps of swirling altermagnetic domains and vortices that were hundreds of times thinner than a human hair.

From tiny vortices to faster and cooler digital devices

Magnetic materials already sit at the heart of hard drives, memory chips, and many sensors, and they quietly eat a lot of power in data centers that show up on someone’s electric bill. The Nottingham team argues that magnetic materials could combine the speed of ferromagnets with the low stray fields of antiferromagnets, which would make it easier to pack bits densely without them interfering.

In their press material, physicist Peter Wadley explains that in these materials the microscopic magnetic moments still point opposite ways, yet each region of the crystal is rotated relative to its neighbor. He describes it as “like antiferromagnetism with a twist” and says that this subtle shift in symmetry can have “huge ramifications” for how fast and efficiently future memory elements might work.

A new chapter in magnetism research is only beginning

The road to this experiment was not short. Theoretical work by researchers such as Libor Šmejkal and colleagues laid out how altermagnets could exist and even suggested candidate materials years before the current imaging study, while other groups in Europe provided early experimental hints that this third branch of magnetism was real.

Senior researcher Oliver Amin says that their measurements “provide a bridge between theoretical concepts and real-life realization” and could guide the search for practical altermagnetic devices, while doctoral student Alfred Dal Din calls it a rare privilege to watch a new class of magnetic materials take shape during a single research project.

For now, these ideas remain mostly in the lab, yet many experts hope that mastering altermagnetic patterns will help design low-energy, spin-based memory and perhaps even shed light on how electric currents behave in advanced superconductors, a question that still keeps physicists awake at night.

The main study has been published in the journal Nature.