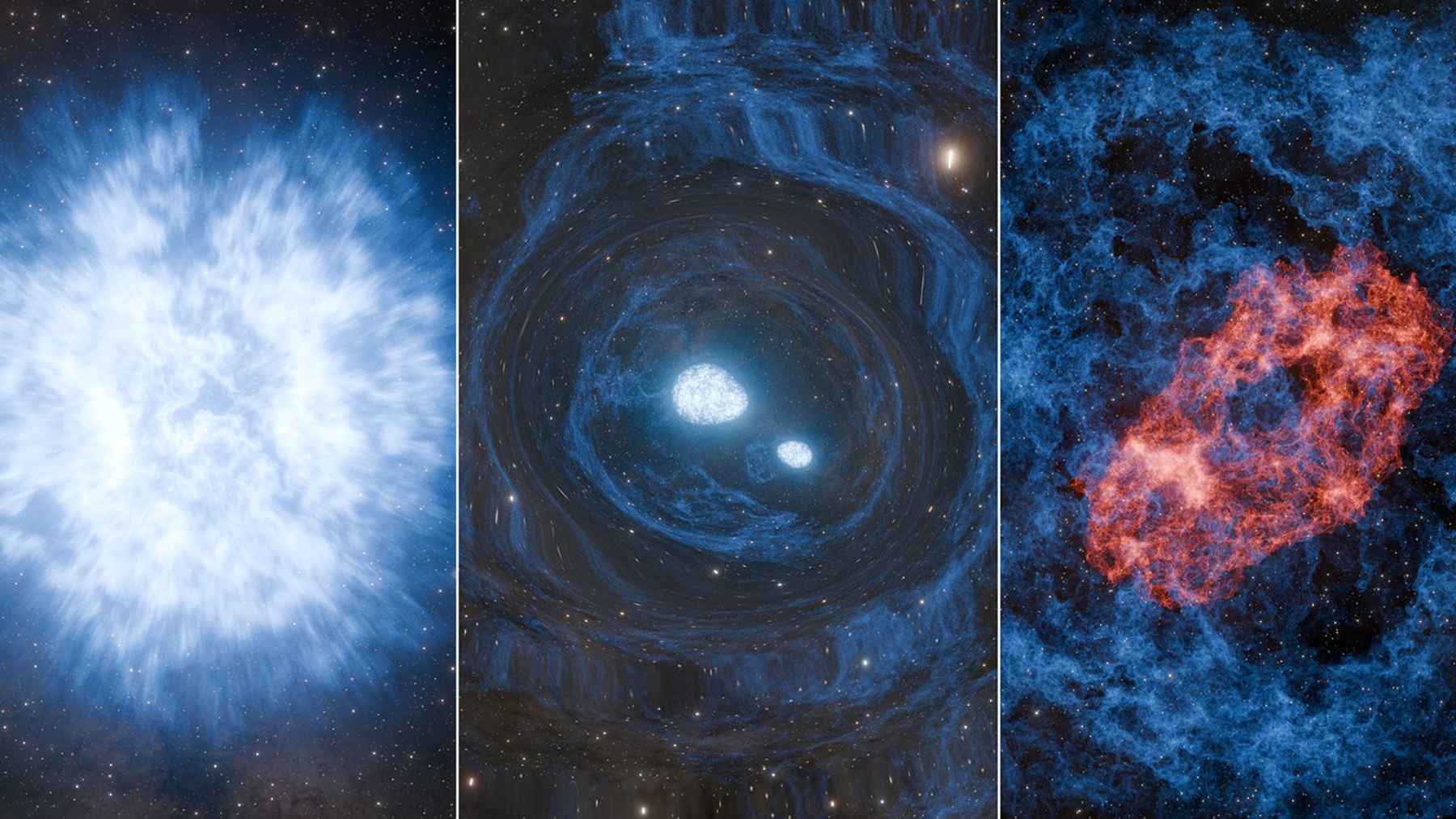

China’s artificial sun has just done something fusion scientists spent decades thinking was impossible. Experiments on the fully superconducting Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak (EAST) in Hefei pushed super hot plasma to densities far beyond a long-standing safety limit, while keeping it stable.

According to a new study and official announcements from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the team reached a long-theorized “density free regime” that could help future reactors produce more energy from the same fuel.

The breakthrough centers on plasma density, which is basically how many particles of fusion fuel are packed into the reactor at once. In deuterium-tritium fusion, the fuel must reach temperatures of around 150 million degrees and fusion power rises roughly with the square of the plasma density.

That is why learning how to safely pack more fuel into the reactor, without blowing it apart or damaging the walls, matters for everything from future climate goals to the electric bill you pay each month.

What is the Greenwald density limit?

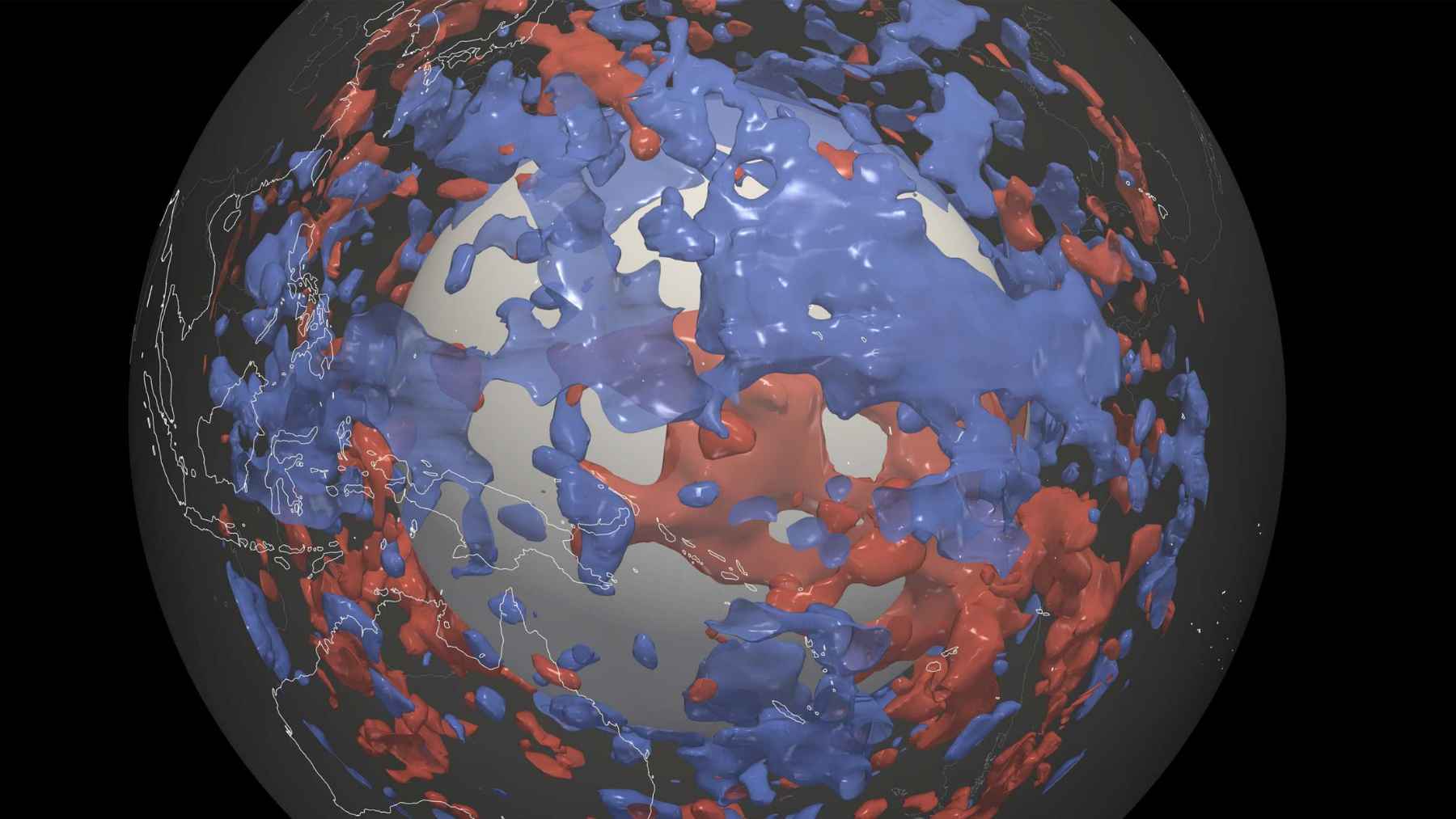

Most tokamaks, including EAST, have long been constrained by something known as the Greenwald density limit. Above this threshold, the swirling plasma tends to become unstable, leaks out of the magnetic cage, and dumps heat onto the inner walls, which can end a pulse in a violent disruption.

For decades that limit acted like a ceiling on performance. EAST usually operated at densities between about 80 and 100 percent of that value, and other machines around the world followed similar rules of thumb.

Pushing harder often meant the plasma would cool, fill with impurities from the walls, and crash, so engineers simply stayed below the red line and asked a nagging question in the background: what if that ceiling could be moved much higher instead?

How EAST pushed plasma beyond old boundaries

In the new experiments, a team led by physicist Jiaxing Liu and Professor Ping Zhu at Huazhong University of Science and Technology worked with associate professor Ning Yan at the Hefei Institutes of Physical Science to rethink how EAST starts each plasma pulse.

They prefilled the vessel with a relatively high pressure of deuterium gas, then used powerful microwave heating called electron cyclotron resonance heating to help the standard Ohmic startup bring the plasma to life.

By tuning those early steps, the team could shape how the super hot gas touched the tungsten-lined divertor plates that sit at the bottom of the reactor and handle waste heat. The carefully balanced conditions reduced the amount of wall material knocked into the plasma and cut energy losses, so the plasma density could climb without tripping the usual instability alarms.

In numbers, EAST reached line averaged electron densities between 1.3 and 1.65 times the Greenwald limit, compared with its typical range of 0.8 to 1.0. Crucially, the plasma stayed under control in this ultra-dense state instead of tearing itself apart, which is exactly what past experience had led engineers to expect. That is the part fusion researchers have been chasing for years.

A long-predicted density free regime

The result does more than break a record. It also backs up a newer idea in fusion physics called plasma wall self organization, developed by theorist Dominique Franck Escande and colleagues at the French National Center for Scientific Research and Aix-Marseille University.

According to this theory, if the plasma and the metal wall reach just the right balance, a new density free regime appears where the usual limit effectively moves far upward. In that state, the wall still erodes and emits impurities, but in a way that no longer triggers runaway cooling and disruptions, especially when heavy elements like tungsten make up the divertor surface.

Earlier experiments on devices such as the DIII-D National Fusion Facility and the Wendelstein 7-X had hinted that higher density operation might be possible with careful fueling and heating. EAST is the first tokamak to show clear experimental evidence of the density free regime that theory predicted, with its measurements lining up closely with detailed models.

What it means for future fusion power

For everyday life this still feels distant, of course, since EAST is an experiment and not a power plant that can cut anyone’s electric bill yet. The reactor still consumes more energy than it produces and other hurdles remain, from materials that can survive relentless bombardment to running high-performance plasmas for hours instead of seconds.

Even so, as Ping Zhu explained, “The findings suggest a practical and scalable pathway for extending density limits in tokamaks and next generation burning plasma fusion devices.”

The EAST team plans to apply the same strategy to higher confinement operating modes and future devices, work that could inform international projects such as ITER and China’s own next generation reactors.

At the end of the day, the research suggests a practical way to pack more fuel into the reactor without crossing dangerous stability lines, bringing the vision of clean, almost limitless fusion power a little closer to reality, even if the clock on climate change keeps ticking faster.

The main study has been published in Science Advances.