Across the planet’s great river deltas, the ground is dropping faster than the ocean is rising. A new global study in the journal Nature finds that in 18 of 40 major deltas, land subsidence already outpaces local sea level rise, raising near-term flood risk for about 236 million people.

River deltas cover only about 1% of Earth’s land surface, yet they support an estimated 350 to 500 million people, from small fishing villages to sprawling megacities. We usually picture climate-driven sea level rise as water creeping higher on a fixed shoreline.

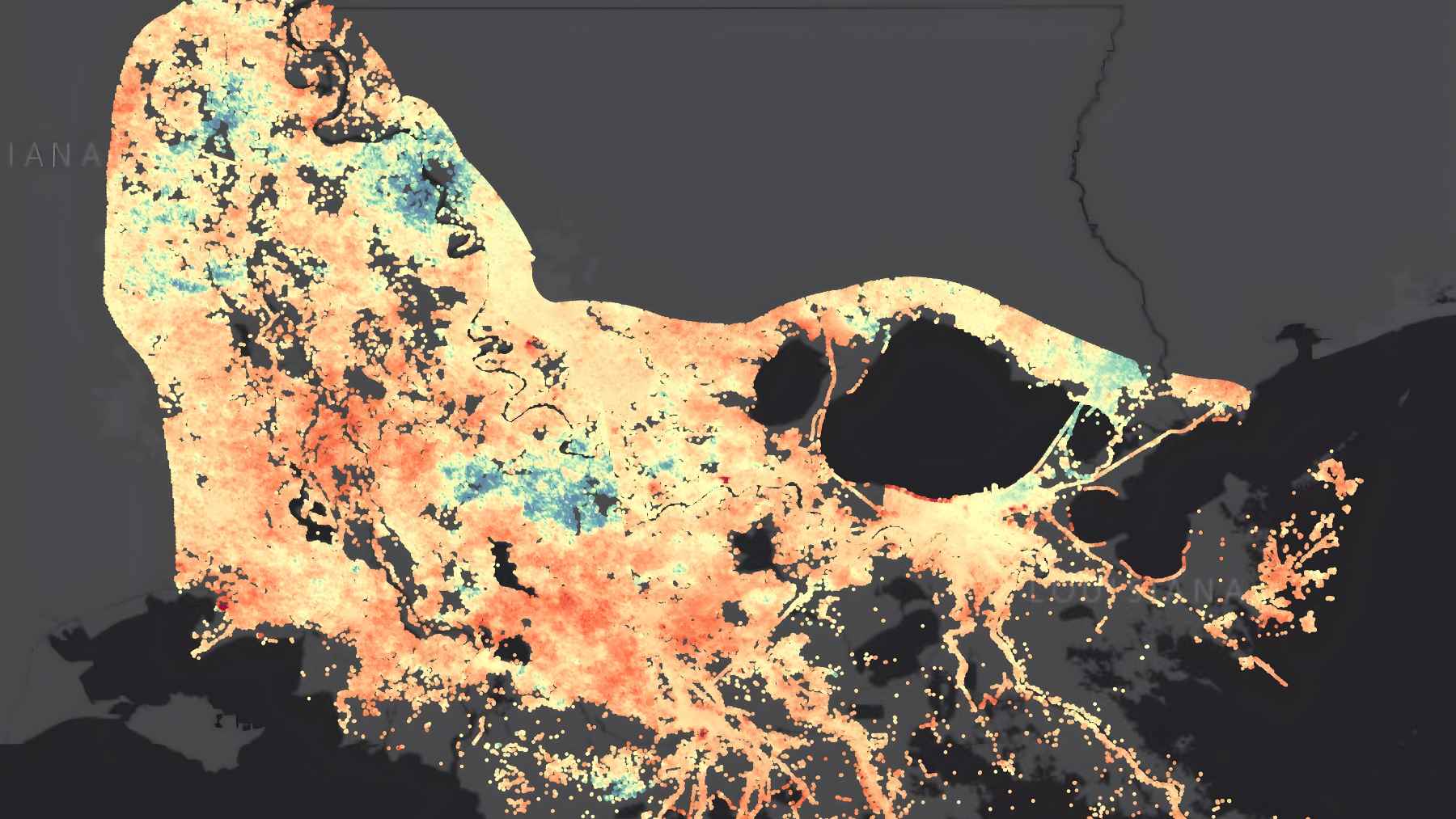

What happens when the shoreline itself is sinking. The new study, led by Leonard Ohenhen of the University of California Irvine, uses satellite radar to measure subtle vertical ground movement across 40 deltas on five continents.

The pattern that emerges is stark. More than half of the deltas studied have average sinking rates above 3 millimeters per year, and in 13 deltas those averages already exceed the current global sea level rise of about 4 millimeters per year.

In almost every system, at least some parts of the landscape are dropping faster than both global and regional sea level trends, including major deltas such as the Mekong, Ganges Brahmaputra, Chao Phraya, Nile and Mississippi.

Cities feel this shift in very practical ways. Coastal hubs including Alexandria, Bangkok, Dhaka, Kolkata, Shanghai and Jakarta are sinking as fast as or faster than their surrounding deltas, which turns heavy rains and high tides into flooded streets more often.

The study estimates that 76 million people live on delta land below 1 meter in elevation. Of those, about 84%, or 63.7 million people, are in zones where the ground is sinking rapidly, meaning relative sea level is driven more by land motion than by the global ocean average.

So why are deltas collapsing? The team compared three human-driven pressures: groundwater depletion, reduced river sediment supply and urban expansion. Groundwater loss emerged as the strongest overall predictor of sinking in many systems, especially in heavily pumped Asian deltas.

As co-author Susanna Werth explains, “When groundwater is over pumped or sediments fail to reach the coast, the land surface drops”. Dams and levees that trap sediment, and concrete that adds weight and alters drainage, also play important roles.

These processes are tightly tied to everyday choices. Turning on a tap in a delta megacity, drilling a farm well, or paving wetlands for new housing can, to a large extent, contribute to the slow settling of the ground.

As Ohenhen notes, “In many places, groundwater extraction, sediment starvation and rapid urbanization are causing land to sink much faster than previously recognized”. Yet the authors stress that subsidence is directly linked to human decisions, which also means solutions lie within our control.

Using the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative index, the team found that roughly two thirds of the deltas face high relative sea level rise with low readiness to adapt, often in low- and middle-income countries.

Even in wealthier regions such as the Rhine Meuse and Mississippi deltas, decades of land loss show that engineering alone has not kept pace with sinking land and rising water. At the end of the day, how societies manage groundwater, river sediment and urban growth will decide whether many deltas stay above the tides.

Next time you read a headline about rising seas, remember that in some of the world’s most important deltas, the bigger story is the sinking shore.

The study was published in Nature.