High in the Perseus constellation, about 1,000 light years from Earth, a very young star is scribbling its life story into space. Astronomers using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and the U.S. National Science Foundation’s Very Large Array (VLA) have found more than 400 delicate rings inside a supersonic jet from the protostar SVS 13. Each ring acts like a time stamp of a past eruption, giving scientists a rare chronicle ofhow a star grows and how future planets around it may be shaped.

For people used to thinking about climate, oceans, or forests, this might sound very far away. Yet these outbursts help decide how material in a young disk clumps together into rocks, worlds, and eventually the kind of planet where air, water and life can exist at all. In a quiet way, this newborn star is writing the preface to some future planet’s environmental story.

Discovery of a cosmic “bullet trail”

SVS 13 sits inside NGC 1333, one of the closest star-forming regions to Earth and a favorite target for telescopes that study stellar nurseries. Decades ago, radio images from the VLA revealed that SVS 13 is a double system, with two infant stars known as VLA 4A and VLA 4B. The same observations showed a string of fast moving clumps of gas, nicknamed molecular bullets, along with glowing Herbig–Haro shock fronts where the jet slams into surrounding material.

Those early data told astronomers that something dramatic was happening, but the details were blurred. Which of the two baby stars was doing the heavy lifting, and how exactly was the jet pushing on its environment. That is where ALMA came in.

How ALMA “CT scanned” a stellar jet

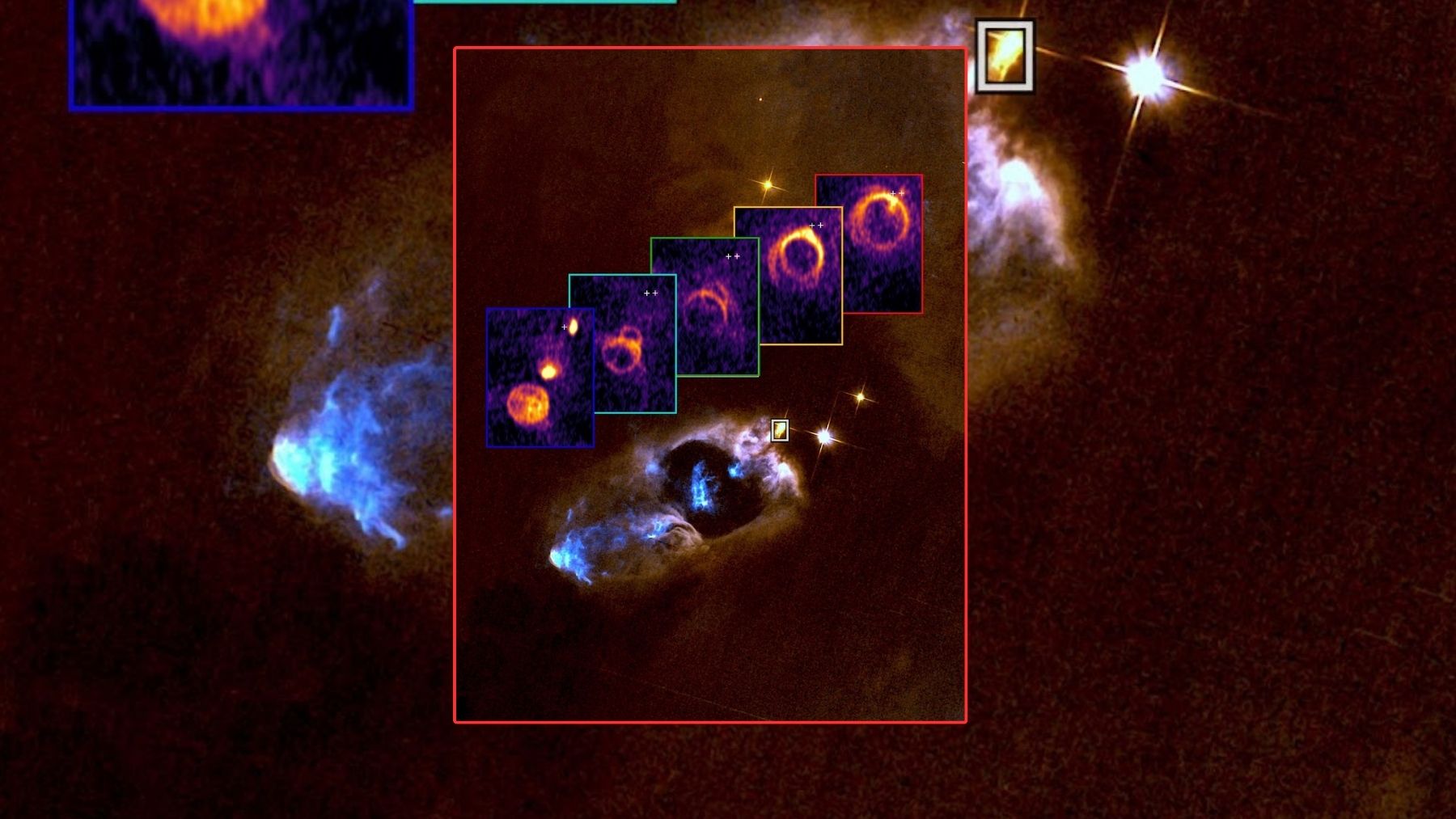

The new study zoomed in on the brightest bullet in the SVS 13 outflow using ALMA’s extremely sharp view at millimeter wavelengths. Instead of a single lump, astronomers saw a nested sequence of hollow rings of carbon monoxide gas. As they stepped through different gas velocities, each ring shrank and shifted position, tracing an ultra-thin bow-shaped shell only a few dozen astronomical units thick and racing outward at up to about 100 kilometers per second.

One researcher compared this to a medical scan. By stacking all those velocity “slices,” the team could reconstruct the three-dimensional structure of the jet and its shocks, much like a CT scanner builds a 3D image of a human organ from many thin cuts. The shells match simple textbook models of momentum conserving bow shocks, created when a narrow jet with changing speed plows through ambient gas.

Jets as faithful record keepers

By measuring the size, mass and motion of more than 400 rings, the team found that each shell corresponds to a burst in the jet’s speed, separated by time gaps of a few decades. The most recent shell has an age that lines up with an optical and infrared brightening event from SVS 13 VLA 4B recorded in the early 1990s.

In other words, when the star gulped down material from its disk and flared, the jet responded with a faster pulse that carved a new shell. The lead author Guillermo Blázquez Calero explains that the jets are not just fireworks from star birth but also “faithful record keepers” that store the timing of these violent growth spurts.

Why planet formation experts care

At first glance, a high-speed jet in a distant nebula seems far removed from daily worries about weather extremes or rising energy demand. Yet the physics unfolding around SVS 13 speaks directly to how planetary systems, including our own, get their start. The study suggests that accretion bursts and jet variability repeat every few decades, fast on cosmic timescales. Each burst can shift the snowlines in the surrounding disk, the invisible boundaries where water, carbon dioxide and other volatiles freeze onto dust grains.

Those shifts influence how dust grains stick, grow and migrate. Over millions of years, such changes can determine how much ice and rock end up in different regions of a planetary system, how many Earth-sized planets form, and how much water they inherit. It is a chain that runs from flickers in a young star’s jet to the presence of oceans, air and eventually climate on a solid world.

A new way to read the “baby albums” of stars

The work also confirms a theoretical picture that has been on the books for decades, in which variable jets drive bow shocks that entrain and stir up the surrounding cloud. With SVS 13, astronomers finally have a nearby system where these shells can be mapped ring by ring, almost like tree rings that record wet and dry years in a forest.

Future observations aim to look for similar ring sequences in other young stars. If this pattern turns out to be common, jets could become a powerful tool to reconstruct how often young suns flare up and how that rhythm shapes the disks where planets form. For readers on Earth, watching a distant jet might feel less abstract when you remember that our own planet once grew inside a similar disk, around a star that likely had its own outbursts and bullets.

The study, titled “Bowshocks driven by the pole on a molecular jet of outbursting protostar SVS 13,” was published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

The study was published on the Nature Astronomy website.

Image credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA/Karl Stapelfeldt.