Far from any traffic jam or smokestack, the research ship Chikyu from Japan is quietly testing a new way to power the green economy. This month the ultra-deep drilling vessel began a month-long mission near Minamitorishima Island around 1,900 kilometers southeast of Tokyo to suction mud rich in rare earth elements from roughly 6,000 meters below the surface.

If engineers can keep that slurry flowing, it would be the first time anyone has continuously lifted rare earth bearing seabed mud straight onto a ship.

For policymakers in Tokyo, this is not just an experiment in marine geology. It is a bid to loosen dependence on China which still dominates the global rare earth trade.

After a supply shock in 2010, Japan cut the share of rare earth imports coming from China from about 90% to roughly 60% by backing overseas mines and recycling. Yet for some heavy rare earths used in electric vehicle motors, its reliance on Chinese supply remains close to total.

Since 2018 the government has spent about 40 billion yen (around $250 million) on this deep-sea program and related work. Officials frame it as economic security rather than a quick commercial play, and analysts say the numbers only start to add up if Chinese export controls stay tight and buyers accept higher prices.

A world first at 6,000 meters

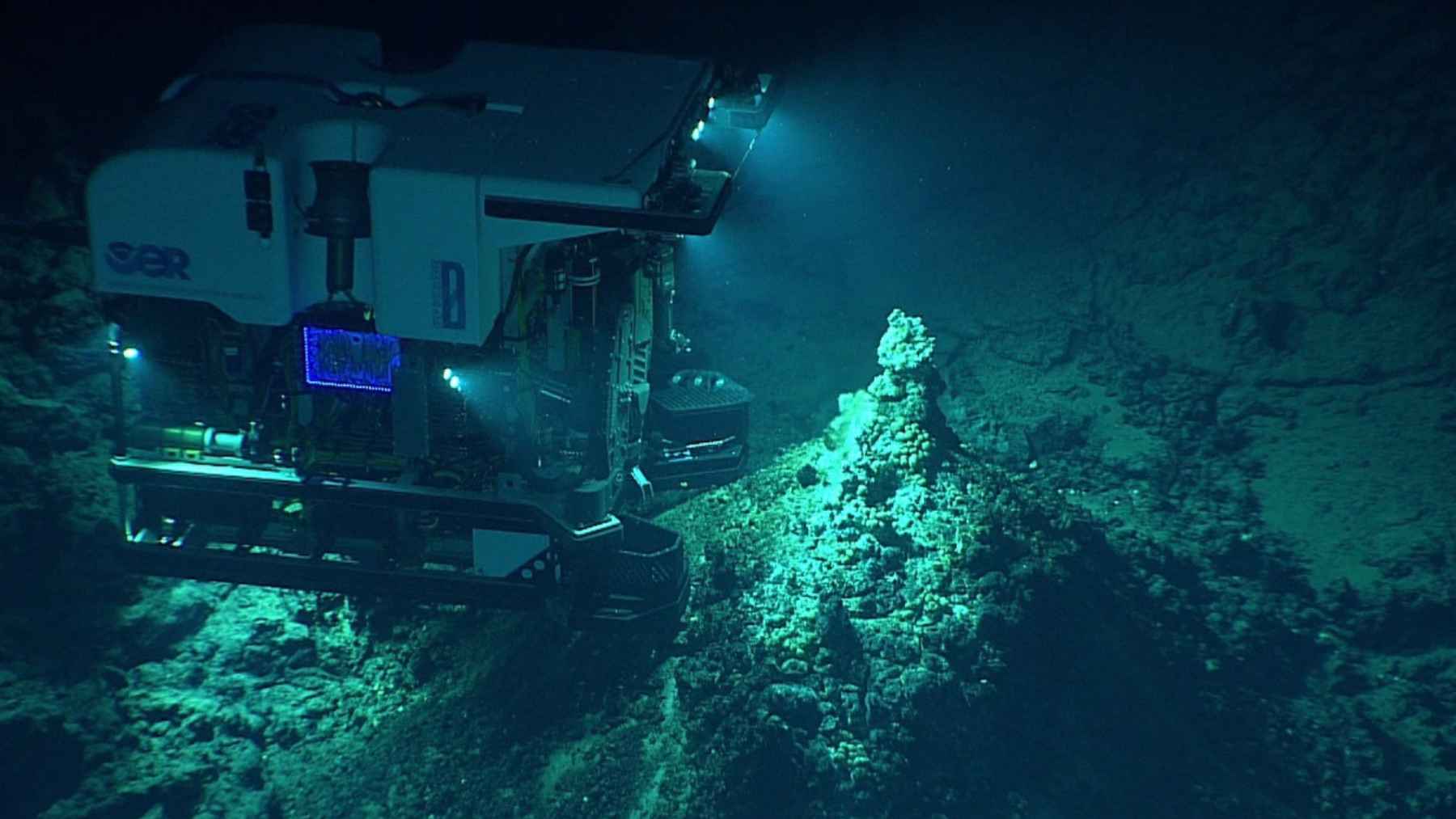

The trial sits under a government effort called the National Platform for Innovative Ocean Developments, known as SIP3, which is coordinated with the Japan Agency for Marine Earth Science and Technology. The plan is straightforward in theory and extremely hard in practice. A long, steel pipe extends from Chikyu down to the seabed.

A mining tool stirs and vacuums soft sediment that is rich in rare earths, mixes it with seawater, and sends the mud up to onboard tanks. Engineers want to prove the system can run steadily and handle up to about 350 metric tons of mud each day while sensors track what happens in the water around it.

If the equipment works and the mud really carries the metal grades earlier surveys hinted at, a larger demonstration is penciled in for 2027. That would move the project from a scientific trial closer to pilot mining, even though no production target has been set and there is still no clear price tag for full-scale operations.

Why this mud matters for clean energy

So why go to all this trouble for ocean mud that most of us will never see. The answer is in the devices sitting on our desks and in the driveways outside. Rare earth elements such as neodymium, dysprosium, terbium and yttrium help make the powerful magnets inside wind turbines, electric vehicle motors, computer hard drives, and many kinds of defense equipment.

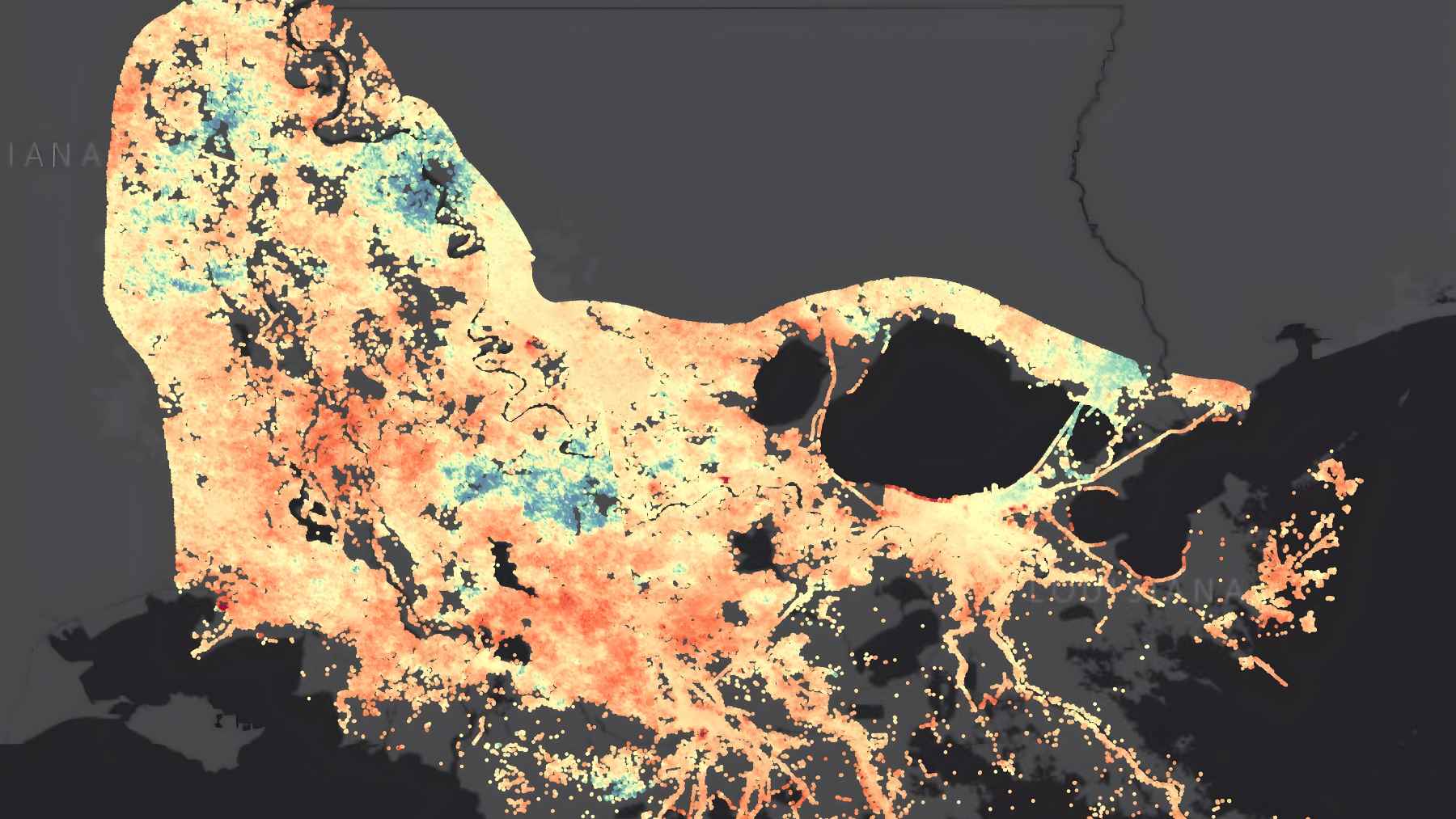

Studies of the Minamitorishima area suggest the surrounding sediments may hold tens of millions of tons of rare earth oxides.

One 2018 estimate pointed to several centuries of global demand for some elements if the resource proves recoverable, a figure that helps explain the intense interest from industry and security planners.

On land, rare earth production often leaves behind toxic waste and radioactive tailings. A report in Nature noted that Japan’s rare-earth-rich ocean mud appears to contain fewer radioactive elements than many terrestrial deposits, which could mean less waste per ton of metal produced.

At the same time the authors warned that scientists still know very little about how deep ocean ecosystems respond to disturbance.

The environmental question mark under the waves

That gap in knowledge is exactly what alarms many marine researchers and advocates. Groups including the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition argue that deep sea mining risks long-lasting and possibly irreversible harm through noise, habitat destruction, and clouds of sediment that can travel far from the mining site.

Around Minamitorishima, the target is not solid rock or metal nodules but very fine mud. Disturb it and a plume of particles can spread through the water, potentially smothering corals, sponges, and other slow-growing deep sea life.

Environmental groups in the Pacific region also worry that metals released from mining could enter food webs that sustain coastal communities many hundreds of kilometers away.

Project leaders respond that this trial is designed to measure, not ignore, those impacts. According to public statements, the system is meant to keep most of the mud inside a closed circuit from seabed to ship and back into storage tanks.

Remotely operated vehicles and monitoring gear will watch how much sediment escapes and how local currents disperse it. Even supporters admit, however, that a one-month test can only provide an early snapshot of ecological change in waters that have evolved over millions of years.

Geopolitics on the seafloor

The mission is also unfolding against a tense diplomatic backdrop. China recently tightened controls on dual-use exports to Japan including some critical minerals, and reports suggest wider restrictions on rare-earth magnets are already biting into supply chains.

That kind of pressure revives memories of the 2010 export halt, when manufacturers scrambled and prices spiked overnight.

For Tokyo and its allies in the Group of Seven, having at least one domestic option for strategic minerals looks like a form of insurance.

Yet specialists at firms such as Nomura Research Institute and Mitsubishi UFJ Research and Consulting caution that extraction is only one piece of the puzzle. Processing, refining, and magnet manufacturing still depend heavily on Chinese capacity, so deep-sea mud on its own will not rewrite the rare earth map.

What to watch next

For now, the crew of about 130 people aboard Chikyu will focus on keeping pumps, pipes, and sensors running in some of the toughest conditions on Earth. The ship is expected to return to port in mid February, after which scientists and engineers will start the slow work of analyzing mud samples, environmental data, and the economics of any next steps.

What does that mean for the rest of us, beyond the headlines. In practical terms the choices made here will help decide how clean technologies are built, how much they cost, and how much damage they inflict out of sight beneath the waves. The trade off is stark. Cleaner air from electric motors on land, set against new risks to little-known life in the deep Pacific.

At the very least this experiment forces a question that usually hides behind our phones and power bills. How far are we willing to go, and where are we willing to dig, in order to electrify modern life.

The official statement was published on JAMSTEC’s SIP3 National Platform for Innovative Ocean Developments.