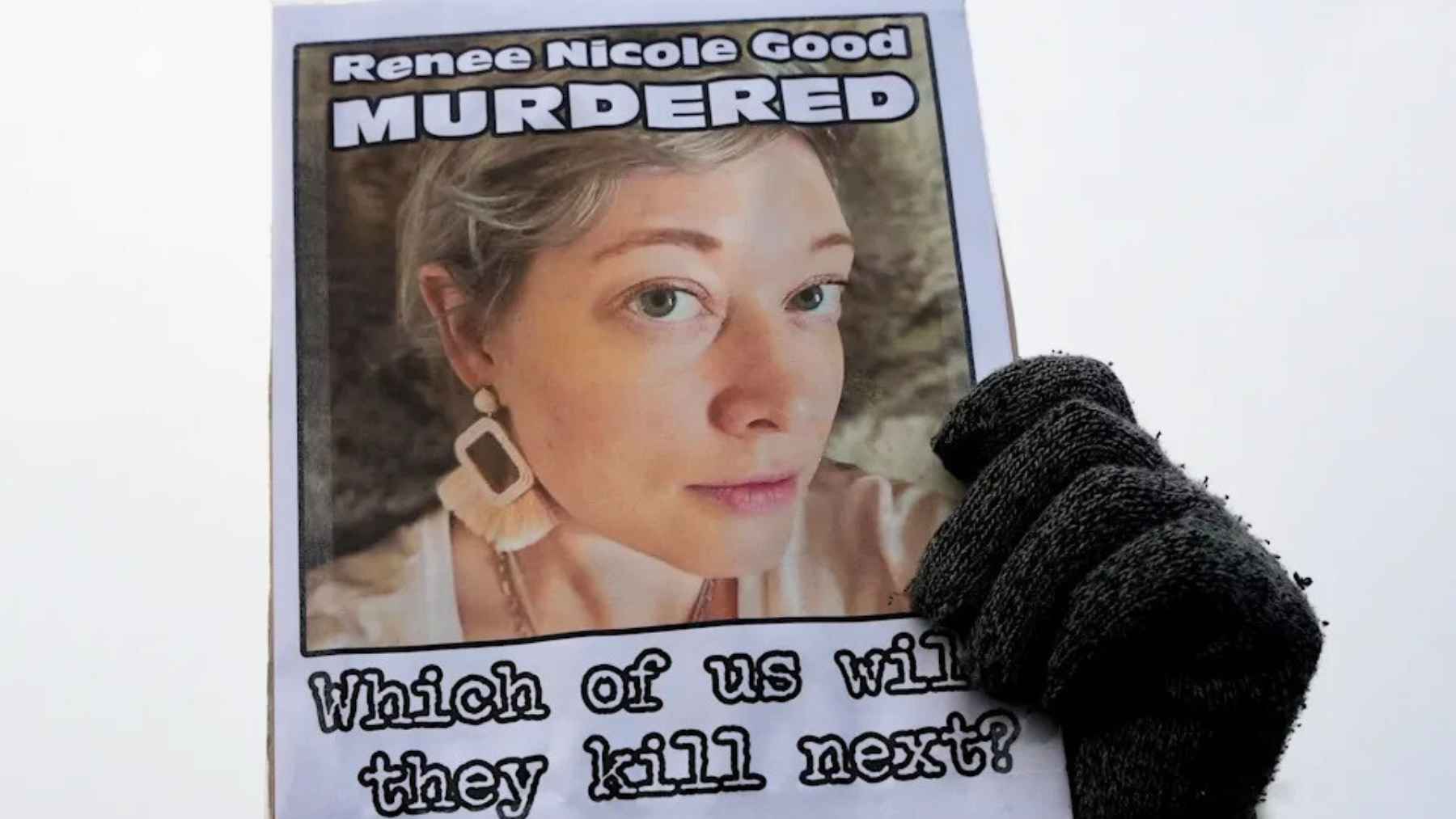

On a snowy morning in Minneapolis, an Immigration and Customs Enforcement officer named Jonathan Ross raised his gun and fired three times into a moving SUV. The driver, 37 year old U.S. citizen Renee Nicole Good, was killed in front of her neighborhood after a tense standoff caught on multiple phones.

Videos and later reporting show her vehicle turning away from Ross as he stood upright beside the front driver side before he shot, a sequence that has fueled protests and deep anger in the Twin Cities and far beyond.

A deadly encounter on a winter street

Good was driving a maroon Honda Pilot when ICE agents converged on her car on Portland Avenue in south Minneapolis. Bystander and officer video show agents reaching into her open window as conflicting orders were shouted, including repeated commands to get out of the vehicle while at least one person nearby urged her to drive.

As she reversed briefly, Ross walked toward the front left of the SUV. Moments later, Good steered forward into the lane of traffic, wheels pointed down the one way street and away from Ross. Staying on his feet beside the driver side, he drew his weapon and fired three shots in under a second, one through the windshield and two through the open window.

Good’s SUV rolled ahead and crashed into a parked car. Emergency records later described her as unresponsive and not breathing when first responders reached the scene, while witnesses told CNN they had seen an officer fire into the vehicle and then watched it slam forward.

For her family, she was not a headline but a mother and writer who had just dropped off her six-year-old child at school.

Border tactics in the heart of a community

Ross is not a rookie. Court records and military documents show he served as a machine gunner in Iraq, later joined the Border Patrol and then became an ICE deportation officer, where he has also worked on a special response team and as a firearms instructor.

Less than a year before he killed Good, Ross was seriously injured in Bloomington when he smashed a driver-side window during an arrest attempt and was dragged along the road as the driver sped off. He testified that he feared for his life in that incident.

The Minneapolis shooting did not happen in isolation. It unfolded one day after the Department of Homeland Security announced what it called the largest operation in its history in Minnesota, sending more than 2,000 federal immigration officers into the state under “Operation Metro Surge.”

Since then, the effects have seeped into everyday life. Somali malls that once buzzed with shoppers now sit half empty, as both citizens and noncitizens say they are afraid to commute, open their shops or even buy groceries in case they cross paths with federal agents.

You can feel the tension in the small details. Store owners keeping passports in their pockets. Parents weighing the risk of a school drop off against the fear of armed officers outside.

The climate crisis is reshaping who moves

So where does the environment come in?

Across the world, climate-related disasters have already displaced around 250 million people in the last decade, according to a recent UNHCR report. That works out to roughly 70,000 disaster displacements every single day, driven by floods, storms, drought and extreme heat layered on top of existing conflict and inequality.

By the end of 2024, nearly 10 million people were still living in internal displacement because of disasters, and many more were uprooted temporarily by storms, fires or floods that never made global headlines.

Looking ahead, the World Bank’s Groundswell modeling, summarized in a 2025 factsheet by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre, suggests that climate impacts could create up to 216 million internal climate migrants across six major regions by 2050 if emissions remain high.

Even that number comes with a big asterisk. The JRC stresses that forecasts for climate migration are “indicative at best,” with wide uncertainty and huge differences between models. In some places, people may actually move less because they are too poor or too constrained to leave at all.

Still, the direction of travel is clear. More extreme weather, more people pushed to the edge, more pressure on already fragile societies.

When climate displacement meets hard borders

Many of the communities now living under the shadow of Operation Metro Surge in Minneapolis, including Somali Americans, have deep ties to regions that sit directly in the path of overlapping climate and conflict crises. The same UNHCR analysis that counted 250 million climate disaster displacements found that three-quarters of refugees and other displaced people already live in countries facing high or extreme climate risk.

In practical terms, that means storms, failed rains, crop losses and heat waves are quietly changing who leaves home and when, often on top of war or political repression. People move first within their own countries, then across borders when local options run out.

The trouble is that wealthier countries have largely responded by hardening borders and expanding interior enforcement instead of matching climate realities with protection and adaptation. In Minnesota, that response takes the shape of convoys of unmarked SUVs, high-profile raids at workplaces and even public schools and a record ICE budget that civil liberties groups say has fueled a pattern of excessive force.

Good herself was a U.S. citizen, which is a reminder that these operations do not stay neatly confined to “foreigners.” Once aggressive tactics are normalized, everyone in the path of a raid or a traffic stop on a cold morning can be at risk.

A climate lens on public safety

Seeing Good’s killing as part of the climate story does not erase questions about accountability in Minneapolis. It adds another layer. If climate change is already displacing hundreds of thousands of people each year and could drive tens or even hundreds of millions to move within their countries in the coming decades, then the choice to answer that reality with militarized enforcement instead of climate resilience is itself an environmental decision.

For the most part, people forced to relocate by drought or flooding are not thinking about national politics. They are thinking about rent, food, school, maybe the electricity bill. When those long chains of cause and effect finally reach a city like Minneapolis, they arrive in the form of neighbors, classmates and coworkers whose lives are suddenly policed by agencies trained for war.

At the end of the day, a climate-conscious approach to public safety would look different. It would pair emission cuts and serious support for adaptation abroad with humane migration pathways and strict limits on the use of force at home. It would treat smartphone videos of encounters with agents not as nuisances but as essential tools for public oversight.

Renee Nicole Good should still be alive to decide for herself what kind of future she wanted in that neighborhood. Her death now sits at the junction of three forces that will shape the coming decades: climate breakdown, mass displacement and the way governments choose to police both.

The study was published by the European Commission Knowledge4Policy.