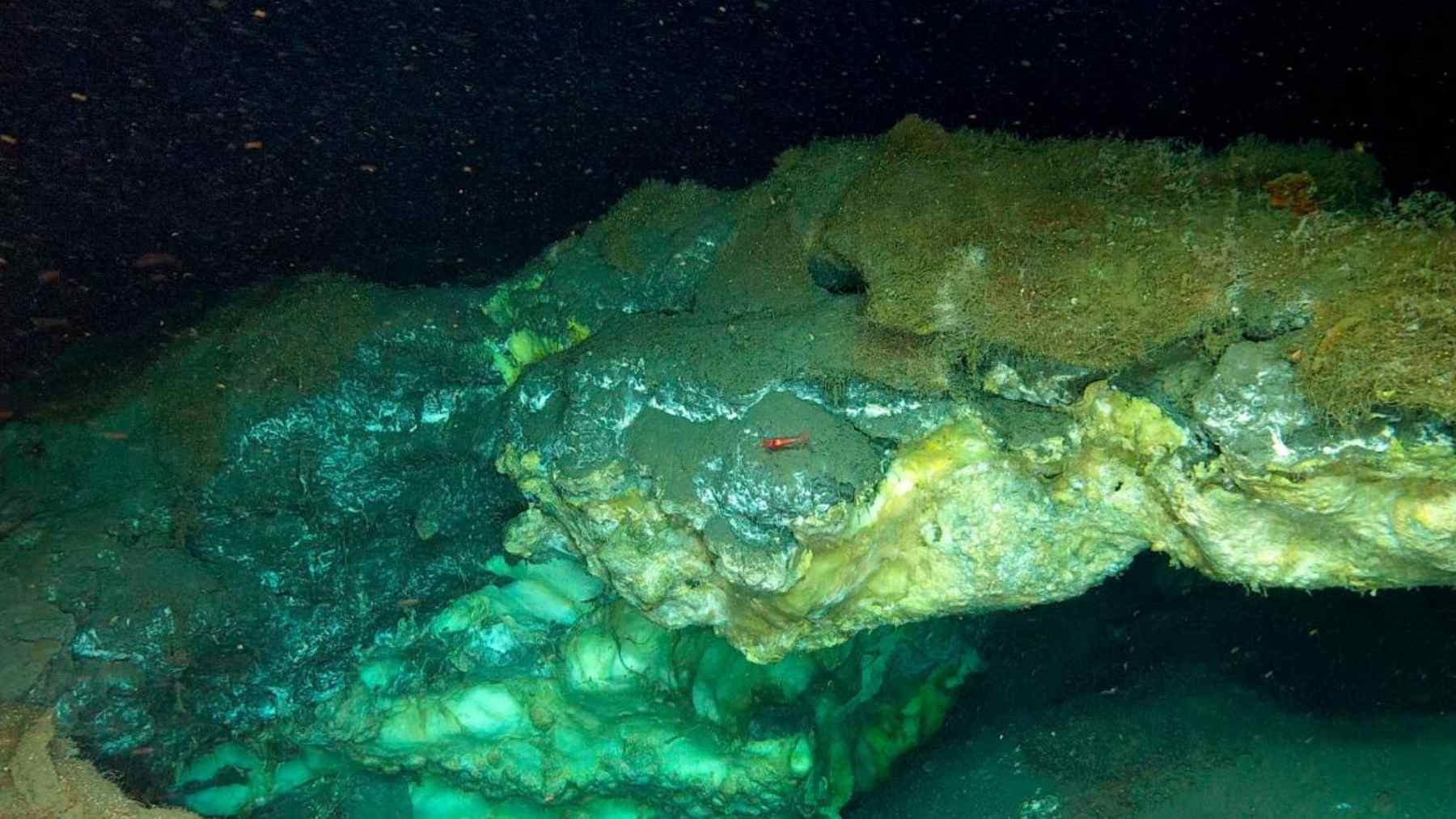

Far below the waves of the Arctic, in water almost four kilometers deep, scientists have found a new kind of oasis. On the Molloy Ridge in the Greenland Sea, at 3,640 meters below the surface, an international team has mapped the Freya Hydrate Mounds, the deepest gas hydrate cold seep ever recorded on Earth.

The site, described in Nature Communications and announced by UiT The Arctic University of Norway, was discovered during the Ocean Census Arctic Deep EXTREME24 expedition in May 2024 using the remotely operated vehicle Aurora. The findings show that exposed gas hydrate deposits can form and persist almost 1,800 meters deeper than the cold seeps previously known, which are usually found in less than 2,000 meters of water on continental slopes.

Giuliana Panieri, chief scientist of the expedition, summed up the surprise. “This discovery rewrites the playbook for Arctic deep sea ecosystems and carbon cycling,” she said, stressing that Freya is both geologically restless and crowded with life in a part of the ocean once considered almost barren.

Deepest fire ice seep yet

Gas hydrates are often nicknamed fire ice. They are crystalline solids that trap gases such as methane inside cages of water molecules, stable only under high pressure and low temperature. Globally, scientists estimate that hydrates lock away roughly 500 to 2,500 gigatons of carbon, making them one of the planet’s largest hidden stores of a potent greenhouse gas.

At Freya, those hydrates push right out of the seafloor. Aurora’s cameras revealed three conical mounds between four and six meters across and up to four meters high, along with collapse pits and low ridges spread over an area roughly 100 by 100 meters. Shipboard sonar traced methane-rich plumes rising more than 3,300 meters through the water column, to within about 300 meters of the surface, among the tallest gas flares ever documented.

Chemical analyses show that the hydrates hold a gas mixture dominated by methane, about two thirds of the total, together with ethane, propane and butane that point to thermogenic hydrocarbons sourced from Miocene age sediments deep in the crust.

Life in a methane twilight

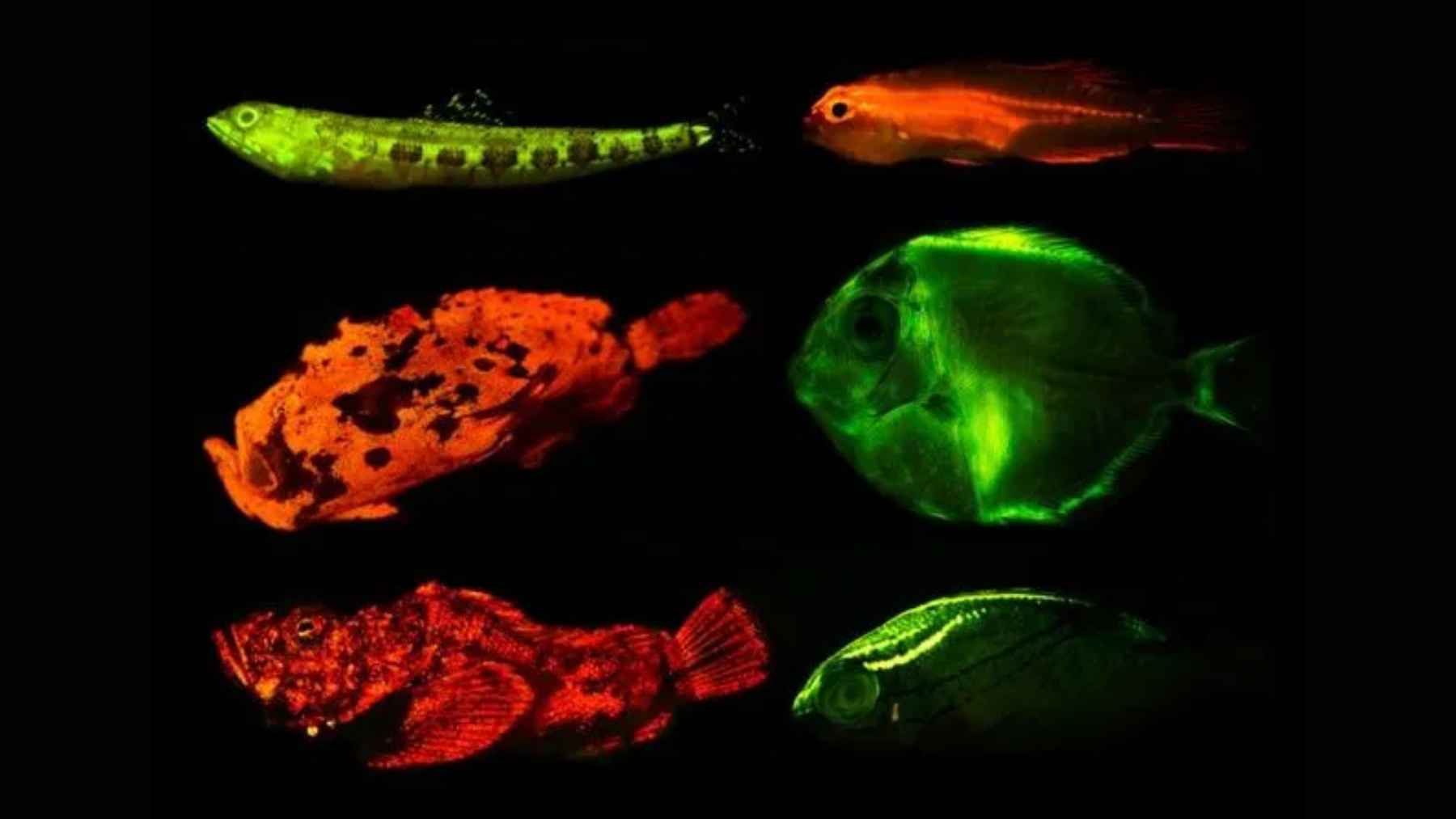

So how does anything live in water that cold, with no sunlight at all? The answer is chemistry rather than photosynthesis. More than twenty faunal types were recorded on and around the mounds, many of them clustered in dense “Sclerolinum forests” of siboglinid tubeworms whose bodies host bacteria that use methane and sulfide as fuel. Snails, amphipods, polychaete worms and small crustaceans move through the tubes, feeding on chemosynthetic microbes or on each other.

The water just above the seabed sits slightly below the normal freezing point of seawater, around minus 0.63 degrees Celsius, yet this chemically powered food web flourishes there. For researchers who track deep sea biodiversity, it is another reminder that Arctic basins often labeled empty on maps in fact host intricate communities tied closely to underlying geology.

Islands of biodiversity on the seafloor

One surprise came from comparing Freya with the recently described Jøtul hydrothermal vent field about 3,020 meters deep on the nearby Knipovich Ridge. At the level of animal families, the community at the methane seep resembles that vent system more than it does shallower cold seeps elsewhere in the Arctic, suggesting strong ecological links between the two habitats.

Jonathan Copley of the University of Southampton, who led the biogeographic analysis, expects Freya to be only the beginning. “There are likely to be more very deep gas hydrate cold seeps like the Freya mounds awaiting discovery in the region,” he said, noting that the animals living there could be vital for the overall biodiversity of the deep Arctic.

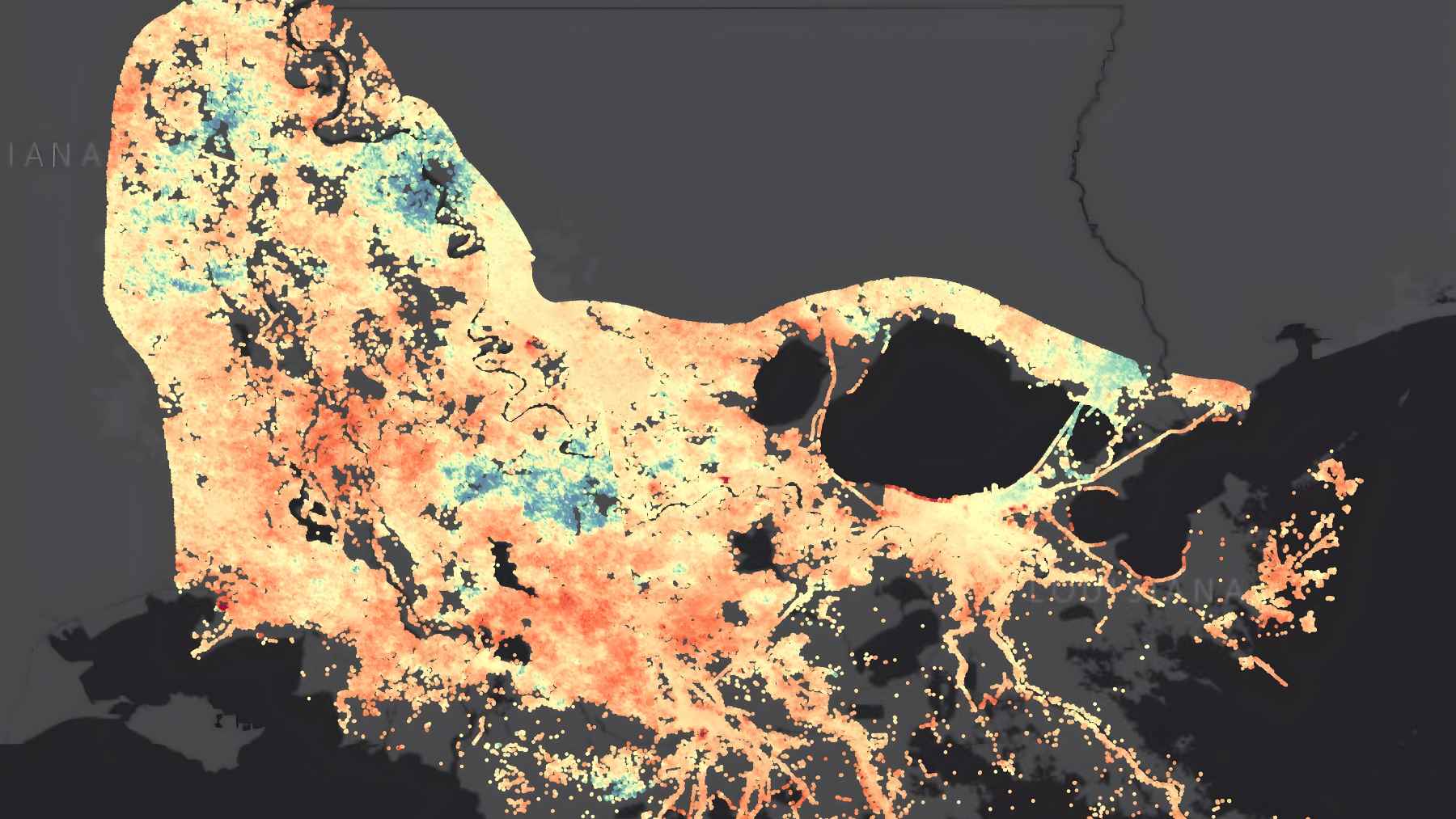

Mining plans on pause

Freya is not only a scientific curiosity. It sits within a wider swath of Arctic seafloor between Jan Mayen and Svalbard that Norway opened for seabed mineral exploration in early 2024, when authorities invited companies to nominate blocks for future mining licenses in search of metals for batteries, wind turbines and other green technologies.

Since then, political winds have shifted. After public pressure and legal challenges, Norway has agreed not to issue any deep sea mining licenses in its Arctic waters and to halt public funding for seabed mineral mapping until at least the end of 2029, a move United Nations experts welcomed as consistent with the precautionary principle and with obligations to protect the ocean and the climate system.

For scientists working on Freya, that breathing room matters. Copley has described vent and seep ecosystems as “island-like habitats” that should be shielded from heavy industrial activity, and Panieri has called the Freya mounds “living geological features” that respond to tectonics, deep heat flow and changing waters in the Fram Strait.

Why this matters beyond the Arctic

At first glance, a patch of hydrate mounds four kilometers down may feel very distant from everyday worries such as storms, fish prices or the electricity bill. Yet the methane stored in hydrates is part of the global carbon system, and the fragile food webs that grow on them are part of the ocean’s wider safety net for biodiversity.

Freya now offers researchers an ultra-deep natural laboratory to watch how methane moves through the water column and how cold seep ecosystems respond as the Arctic Ocean slowly warms. At the end of the day, choices on deep sea mining and climate policy will determine whether this newly discovered forest in the dark remains a thriving refuge or becomes collateral damage in the race for critical minerals.

The study was published on UiT The Arctic University of Norway’s site.

Photo: UiT / Ocean Census / REV Ocean.