For years, a pale, shrimp-like giant from the deep ocean was treated as a rare curiosity. New research now suggests this creature, Alicella gigantea, may actually roam nearly 59 percent of the world’s oceans, hiding in the darkness far below everyday shipping lanes and beach vacations.

The study, led by marine biologist Paige J. Maroni at the University of Western Australia, pulls together almost everything science knows about this animal, from scattered camera shots to precious preserved specimens. By combining those records with modern genetic tools, the team shows that the “supergiant amphipod” is not just surviving in the abyss but thriving there as one widespread, highly-connected species.

A deep-sea giant hiding in plain sight

Alicella gigantea is the world’s largest known amphipod, a type of crustacean related to shrimp and the tiny “sand fleas” that hop around your feet at the beach. Adults can reach about 13 inches long, roughly the length of a laptop or a loaf of bread, which counts as enormous in a group where most relatives are smaller than a fingernail.

These animals live on the deep sea floor in the abyssal zone and the hadal zone, meaning depths from roughly 3,000 down to almost 9,000 meters. At those depths, sunlight never reaches the water, temperatures hover just above freezing, and pressure is hundreds of times higher than at the surface.

Because that environment is so hard to reach, sightings used to be rare. Earlier work, including a 2013 study of specimens from the Kermadec Trench in the southwest Pacific, hinted that A. gigantea might be a globe trotter, but scientists still saw it as an oddity that popped up only once in a while.

How scientists mapped a deep-sea heavyweight

Maroni and her colleagues took a different approach. They gathered 195 confirmed records of Alicella gigantea from 75 locations that span the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans, then mapped where each individual had been found. The animals came from nine deep sea trenches and three fracture zones, at depths between about 3,890 and 8,931 meters.

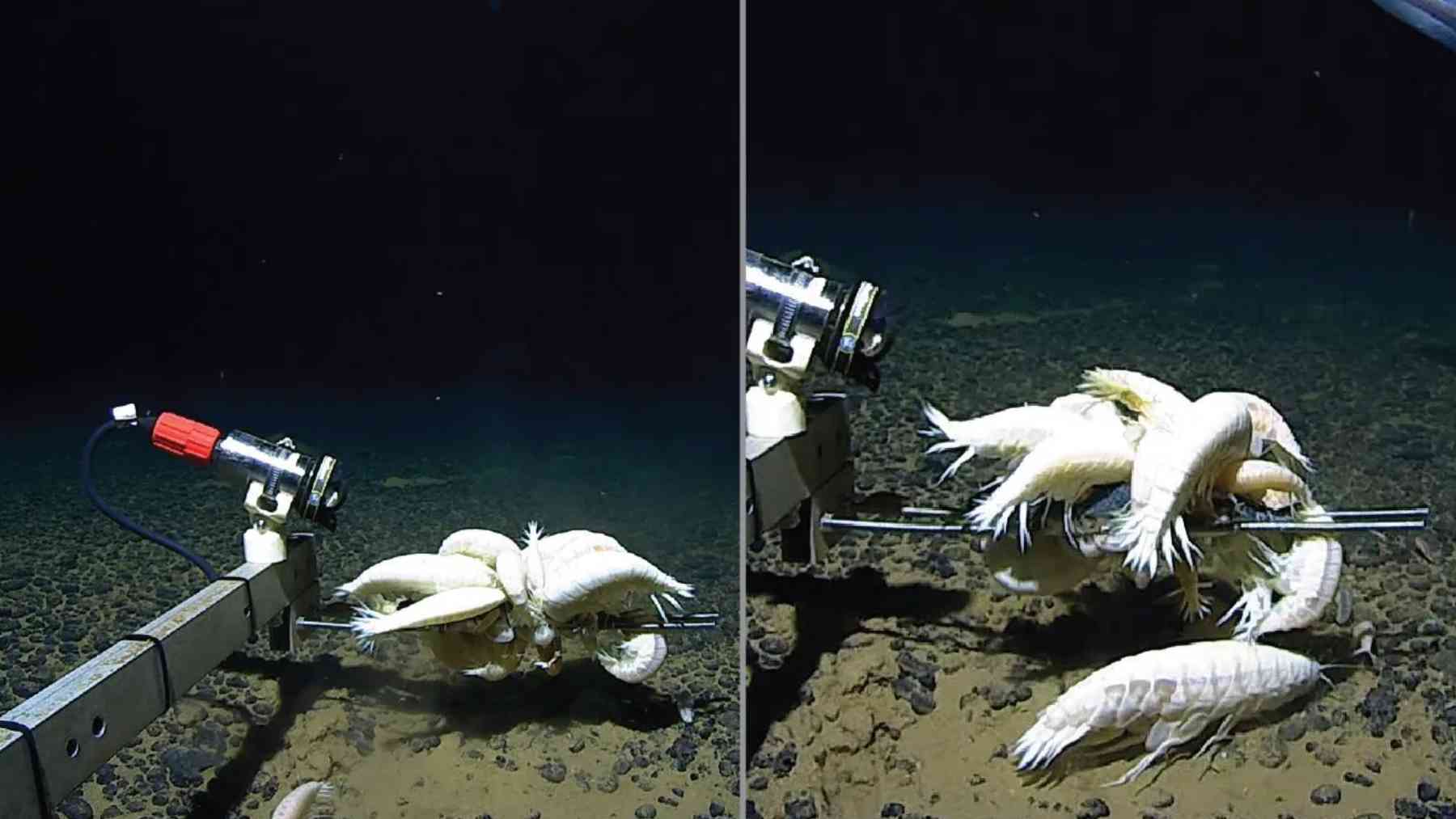

To build that database, scientists relied on baited landers and traps that sit on the seafloor with a camera and a bag of fish, along with high-definition video from crewed and robotic submersibles. In some places, the team saw large groups of the giants swarming bait, a scene that looks a bit like a slow-motion feeding frenzy.

So how did a creature this big stay “rare” for so long? Researchers point to sampling bias, the simple fact that humans have explored only a tiny fraction of the deep ocean. As Dr. Maroni puts it, Alicella gigantea was collected infrequently compared with other amphipods, which made it seem scarce even though populations were likely healthy.

One connected population across the trenches

The new work did not stop at counting records. The team also analyzed DNA from two mitochondrial genes and one nuclear gene in specimens from around the globe. Those sequences showed very little genetic difference between individuals from distant oceans.

In simple terms, that means scientists are looking at a single, widely distributed species rather than a cluster of separate regional types. Some experts suggest that the cold, stable conditions of the deep sea slow genetic change, while shifting ocean currents and plate movements over millions of years may have helped these animals spread.

For everyday life on the seafloor, this connected population likely matters a lot. A. gigantea seems able to move between deep basins and trenches, probably riding currents and following sinking carcasses of fish and whales, which provide rare “buffet” events on an otherwise sparse menu.

Why a hidden crustacean matters for the rest of us

At first glance, a giant ghostly amphipod shuffling along the mud thousands of meters down can feel far removed from daily concerns like the grocery bill or summer heat. Yet creatures like Alicella gigantea help recycle dead material that sinks from the surface and play a role in carbon cycling, which ultimately connects back to climate and the health of fisheries.

The discovery that this species may occupy nearly 59 percent of the ocean floor suggests that deep-sea ecosystems are more connected, and possibly more resilient, than scientists once thought. At the same time, it raises questions about how activities such as deep-sea mining might affect wide-ranging animals that we are only beginning to understand.

Researchers say that continued exploration, along with more genetic work, will be key to uncovering hidden diversity in Alicella gigantea and other deep sea crustaceans. At the end of the day, this “supergiant” shows that some of the biggest surprises on Earth are still unfolding in places no sunlight ever reaches.

The study was published in the journal of Royal Society Open Science.