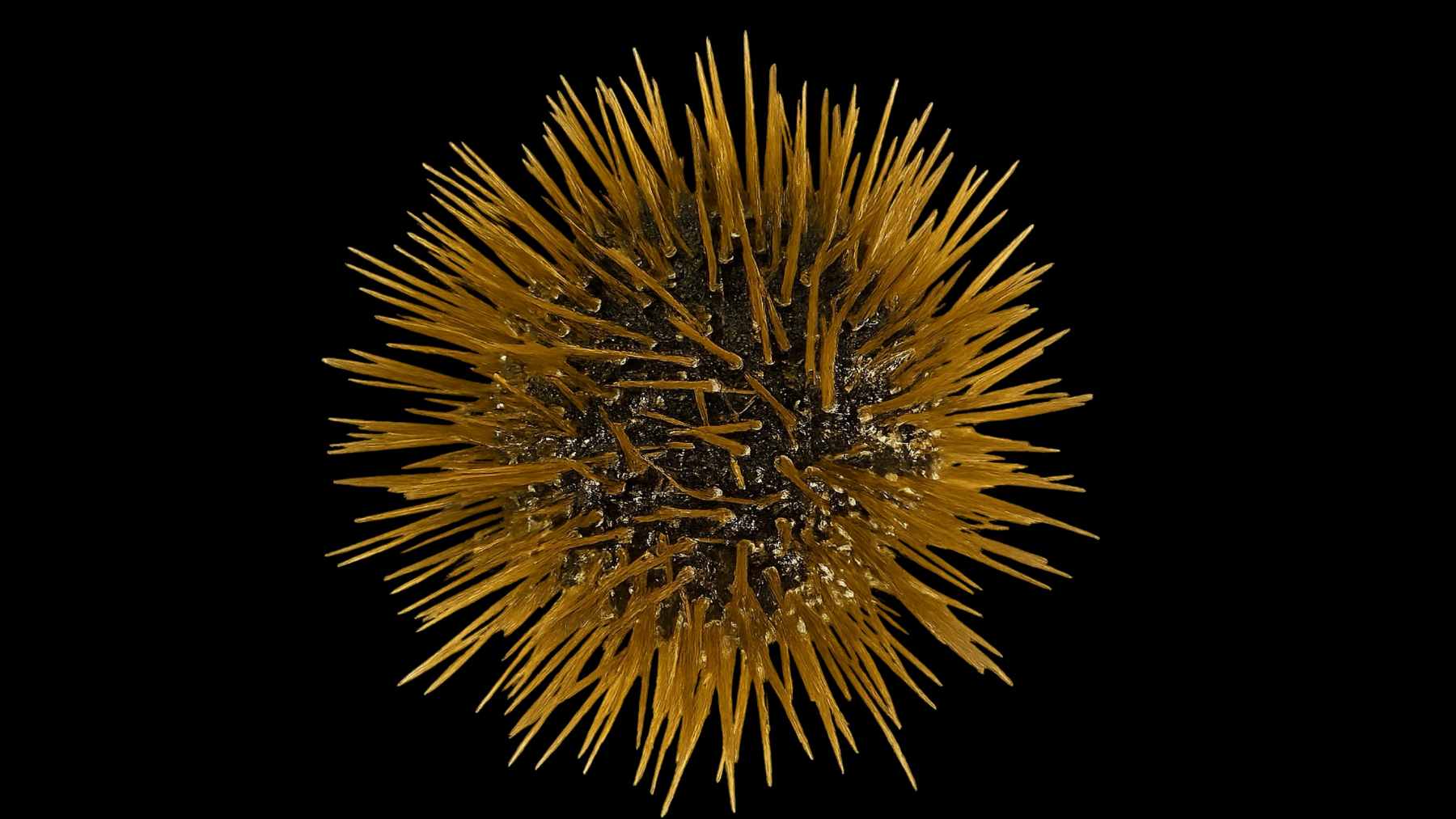

At first glance, the purple sea urchin is just a spiky ball you try not to step on during a beach vacation. Yet a new study finds that this common Mediterranean species, Paracentrotus lividus, is built around an “all‑body brain” that challenges long‑held ideas about how nervous systems and intelligence have to look.

The same animal that ends up as a delicacy in coastal kitchens from Spain to Italy turns out to have a nervous system that rivals parts of our own in complexity. Its entire body acts like a head filled with specialized neurons, rather than a simple creature with no real brain at all.

So what is hiding under those spines?

A spiky animal that is basically a head

For decades, textbooks described sea urchins and their relatives as having a basic nerve ring and a few radial cords, little more than a diffuse nerve net with no central control.

An international team led by researchers in Naples and at the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin looked closer. They built a cell atlas of juvenile P. lividus two weeks after metamorphosis, using single‑nucleus RNA sequencing to profile thousands of cells one by one.

When they grouped those cells by their gene activity, eight major cell type families emerged. Nearly half of the clusters belonged to neurons, split into 29 distinct neuronal families, including 15 different kinds of photoreceptors. Many of these neurons switched on gene programs that closely resemble those used in vertebrate central nervous systems.

Even stranger, the team found that the adult body plan is mostly “head-like”. Genes that usually pattern a trunk in other animals are active only in internal organs such as the gut and the water vascular system, not in the outer body wall. In practice, that means a sea urchin is almost all head, wrapped around a skeleton and plumbing.

As evolutionary biologist Jack Ullrich‑Lüter put it, “animals without a conventional central nervous system can still develop a brain‑like organization”, a result the authors say changes how we think about the evolution of complex nervous systems.

Seeing the world with no eyes and no face

The surprises do not stop there. Sea urchins have no eyes in the usual sense, yet the new work confirms that they are covered in light‑sensitive cells. These photoreceptors sit in the skin and in the tube feet, and they express opsins similar to those found in the human retina.

One cell type even combines melanopsin and Go‑opsin, two light receptors usually associated with sophisticated light detection and day‑night regulation. Large parts of the nervous system appear to respond to light, which means the animal may be reading changes in brightness across its whole body surface.

Imagine walking around with your skin acting as a low‑resolution camera. For a sea urchin, that is simply everyday life on the seafloor.

Rethinking intelligence in a more‑than‑human world

Researchers are careful not to claim that sea urchins are solving puzzles like an octopus or learning language like a parrot. This study is about neural architecture rather than IQ scores. Still, finding hundreds of vertebrate‑like neuron types in a creature with no head forces a rethink of what counts as a “sophisticated” nervous system.

Humans tend to reserve words like intelligent for animals with familiar bodies and big obvious brains. Chimpanzees, dolphins and crows make the cut. Spiny echinoderms usually do not. Yet the all‑body brain of P. lividus shows that complex information processing can be spread out through tissue instead of packed into a single lump of gray matter.

Engineers are already studying distributed control in octopus arms and insect swarms to design robots that keep working even when parts fail. Sea urchins now join that shortlist as a natural example of a decentralized but highly organized nervous system. At the end of the day, the lesson is simple. Intelligence does not need to be centered in one place.

Why this spiky “brain” matters for the ocean

Beyond the mind‑bending biology, purple sea urchins are key players in Mediterranean coastal ecosystems. P. lividus grazes on a mix of seaweeds and seagrasses, and when its numbers boom it can strip rocky reefs bare, turning underwater forests into so‑called barren grounds dominated by crustose algae.

Those changes ripple outward. Fish that rely on kelp and seagrass lose shelter. Carbon storage in lush plant beds drops. Snorkelers and local fishers feel the difference in what they see and catch.

At the same time, this species is under pressure. Laboratory studies show that ocean warming and acidification can alter sea urchin larvae development and behaviour, and can interact with pollutants and microplastics to increase stress on young urchins.

For coastal communities that harvest urchins and for ecosystems that depend on their grazing, understanding how these animals cope with a changing ocean is no longer a niche question.

Recognizing that even a “simple” sea urchin carries an all‑body brain may not change how you feel about stepping on one. It does underline how much evolutionary experimentation is quietly happening beneath the waves and why protecting those habitats matters for both ecology and basic science.

The study was published in the journal “Science Advances”.

Image credit: Periklis Paganos