If someone asked you to point to ancient Earth, you might think of dinosaur fossils or crumbling mountain ranges. Yet in the middle of Australia, there is something even older quietly carving through the desert. The Finke River, known as Larapinta in the Arrernte language, is widely considered the oldest continuously flowing river system on the planet, with an estimated age between 300 and 400 million years.

That means this river was already winding across the landscape long before the first dinosaurs took their steps on Earth. Today it stretches for more than 400 miles across Australia’s Northern Territory and into South Australia. Because the region is so dry, the Finke usually appears as a chain of waterholes rather than a full raging river, only joining up during rare heavy rains.

A river older than its mountains

One of the most striking things about the Finke is where it flows. Instead of bending politely around hard rock, the river cuts directly across the MacDonnell Ranges, a rugged spine of mountains in central Australia. Geomorphologist Victor Baker describes this kind of system as an antecedent river, meaning the river was already there before the mountains slowly rose beneath it. As the crust was pushed upward during the Alice Springs Orogeny, roughly 400 to 300 million years ago, the Finke kept slicing downward and held its course.

This unusual cross-cutting pattern is a big part of why scientists are confident about its extreme age. Meanders usually form on flat plains. When you see deeply-carved bends now trapped within mountain gorges, it suggests the landscape moved around the river, not the other way around.

Dating a river that old

Of course, nobody can look at a river and simply read its birthday. Researchers rely on a mix of clues stored in rocks and sediments. Weathering profiles show how long surfaces have been exposed to air and flowing water. Radioactive isotopes in minerals act like tiny clocks, because they decay at known rates over millions of years. By comparing these chemical signatures around the Finke, geologists place the river’s origins in the Devonian or Carboniferous period, roughly 300 to 400 million years ago.

In practical terms, that makes the Finke not just older than dinosaurs, but older than many of the continents in their current shapes. It is a survivor from a very different Earth.

Tectonic calm kept the river alive

So why did this river persist while so many others vanished or were rerouted by time, ice, and tectonic chaos? The answer lies beneath our feet. The Australian plate has been remarkably stable for hundreds of millions of years, far from the violent collisions and subduction zones that reshape other continents.

Unlike Europe or North America, central Australia was never bulldozed by massive ice sheets during the recent ice ages. In many parts of the world, glaciers scraped away valleys, buried old channels, or forced rivers into new paths. In the Finke basin, there was no such reset button. That tectonic calm allowed the ancient channel to keep draining the same highlands again and again.

A fragile oasis in a warming climate

For most of the year, the Finke is a series of isolated pools that act as life support for desert ecosystems. These waterholes offer crucial refuges for fish, invertebrates, birds, and thirsty wildlife during long dry spells. Studies of similar arid zone rivers in Australia show that waterholes function as key aquatic refuges, yet they are highly sensitive to changes in rainfall and evaporation.

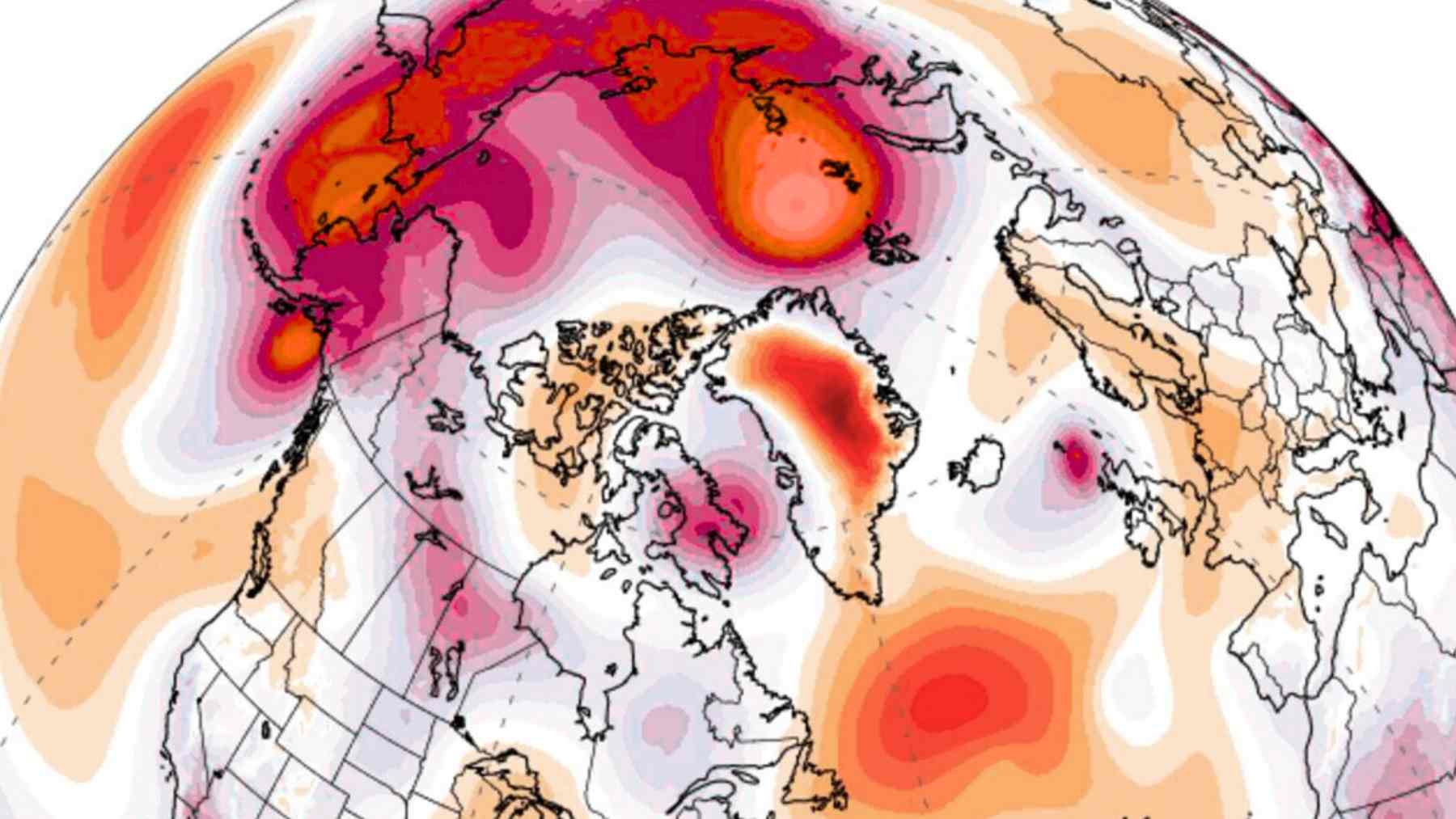

Climate projections for Australia point to continued warming along with shifts in rainfall patterns and more frequent droughts. Higher temperatures increase evaporation from already shallow pools. In drier scenarios, scientists have modeled dramatic reductions in waterhole area in ephemeral rivers, which means less habitat and more stress for species that depend on these last pockets of water.

On top of that, growing water demand from towns, tourism, and industry in arid regions can further squeeze an already limited supply. The Live Science analysis warns that increased water consumption together with climate change could threaten the longevity of the Finke system itself.

What an ancient river can teach modern societies

At first glance, the Finke might seem far removed from daily life, especially if you live in a city and mostly think about water when the bill arrives. Yet researchers who study river resilience note that healthy, connected channels can act as natural shock absorbers, soaking up floods and supporting biodiversity even as conditions change.

The story of the Finke is a reminder of two things. First, natural systems can be incredibly persistent when the physical setting is stable. Second, even the most durable landscapes have limits once human-driven climate change and extraction are added to the mix.

A river that has already outlived entire eras of life on Earth now faces pressures that emerged in just a few human generations. Protecting its fragile waterholes and the species that depend on them will require careful management of groundwater, surface flows, and land use in Australia’s interior, along with rapid cuts in global greenhouse gas emissions.

If we succeed, the Finke could keep tracing its ancient path across the desert for many millions of years to come, still quietly following the same course it carved before dinosaurs, mammals, or people ever appeared.