For more than a decade, fleets of dredgers have been pouring sand onto remote reefs in the South China Sea, turning shallow coral platforms into solid ground with runways, ports, and radar domes. What looks like a technical triumph from space comes with a heavy ecological bill under the waves.

Scientific studies now show that this construction has smothered coral reefs, clouded vast areas of water, and put one of the planet’s richest marine ecosystems under even greater stress.

How to build an island on top of a reef

Engineers started with low-tide features that barely broke the surface. Cutter suction and hopper dredgers scraped sand and rubble from nearby seabeds and pumped the slurry onto reefs such as Mischief, Subi, and Fiery Cross. Bulldozers then leveled and compacted the new material, while concrete walls tried to hold the whole structure in place against waves and storms.

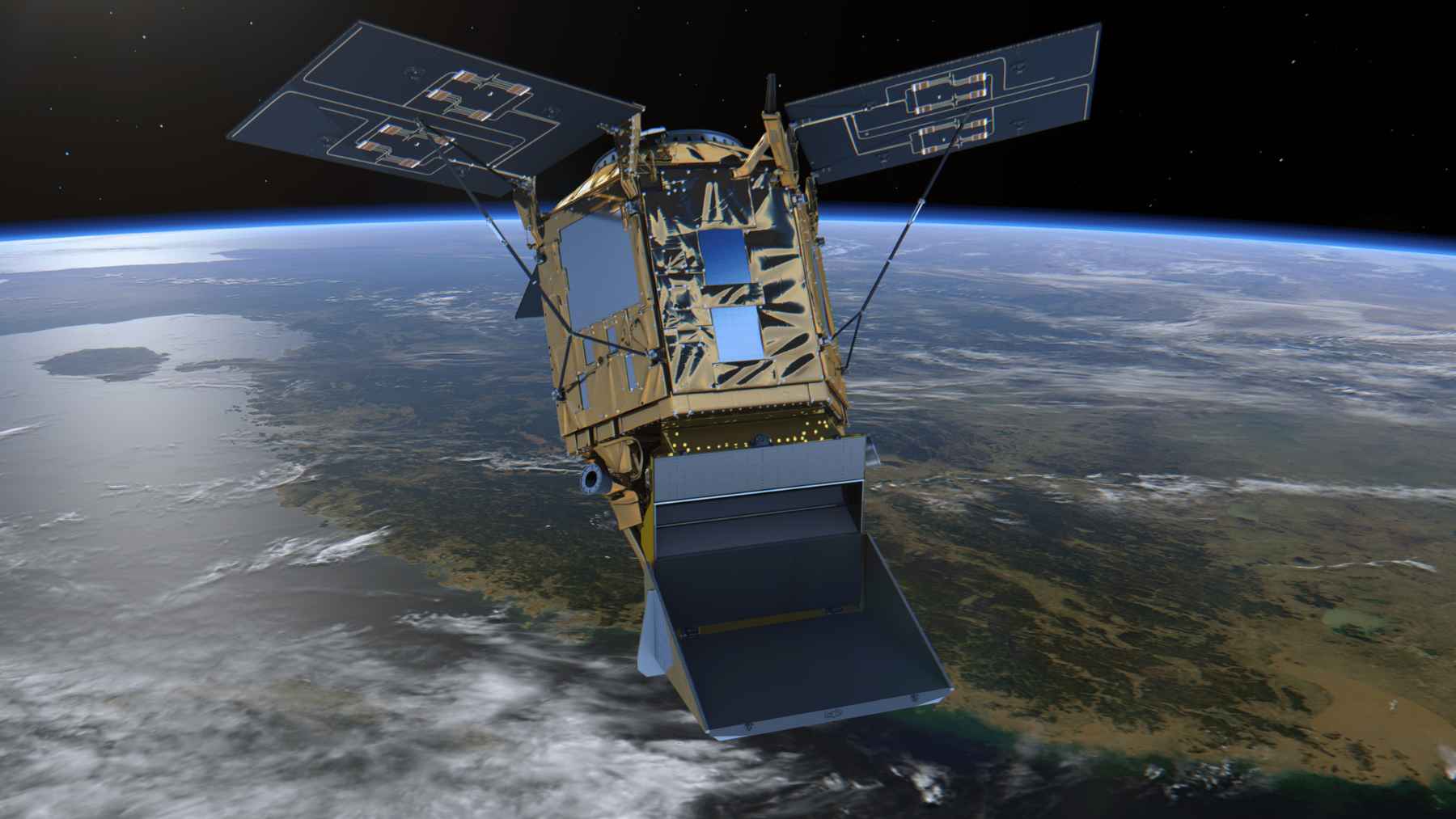

From orbit, the change is stark. A 2016 study using Landsat data estimated that more than fifteen square kilometers of submerged coral reef were converted into artificial islands between mid 2013 and late 2015, mostly by China.

A later analysis in Scientific Reports found that China built about 3,200 acres of new land in the South China Sea between 2013 and 2017. In practical terms, that is thousands of football fields of former reef replaced by concrete and fill.

Once the outline is fixed, the islands are fitted with power plants, desalination units, fuel depots, and storage. Some patches of imported soil and trees soften the view, but ecologists remind us that the true foundation is living rock that has been buried rather than respected.

Sediment plumes and “ghost” reefs

The most visible damage to coral reefs does not end with the new shoreline. It spreads outward in cloudy plumes. The 2016 satellite study detected turbidity plumes linked to island building that together covered more than 4,300 square kilometers of surrounding waters.

A 2019 case study at Mischief Reef went further. Using ocean color data, researchers measured backscatter increases of up to 350 percent in nearby waters and estimated that dredging and construction affected more than 1,200 square kilometers over time.

Those suspended sediments act like a dust storm in the sea. They block light, clog coral polyps, and settle onto seagrass beds and other benthic habitats.

The same study found changes in chlorophyll and other optical signals that point to declining biological health around the construction site, consistent with reefs and associated communities being smothered. Once complex coral structures die back, fish lose shelter and feeding grounds. What used to be a vibrant three-dimensional city becomes a flattened, muddy lot.

Why this matters far beyond disputed rocks

At first glance, all this might sound like a distant quarrel over faraway sandbars. Yet the South China Sea is a key artery for the global economy and a pantry for millions of people. Roughly one-third of global maritime trade by volume passes through these waters, carrying everything from smartphones to grain.

Biologically, the stakes are just as high. The region sits on the edge of the Coral Triangle and hosts one of the highest concentrations of marine biodiversity on Earth. One recent assessment notes that hundreds of reef forming coral species and thousands of fish species rely on South China Sea habitats. For coastal communities, those reefs are not an abstract wonder. They are protein on the plate and income at the dock.

When island building destroys nursery grounds and disrupts currents that carry larvae, the effects ripple far beyond the footprint of any one runway. Experts warn that this disturbance piles on top ofwarming seas, acidification, and heavy fishing pressure.

A new coastline in a warming world

Unlike natural islands, these new platforms do not grow with the reef. They constantly battle erosion, salt, and storms while the corals beneath them are already gone. That leaves the surrounding ecosystem with fewer buffers just as climate-driven bleaching events become more frequent.

For people far from Asia, the connection can feel indirect. Yet any shock to South China Sea fisheries and shipping can eventually show up in seafood prices, freight costs, and even the availability of certain products in supermarkets. At the end of the day, manufactured land in one contested sea is entangled with everyday life in places that will never see these islands firsthand.

Scientists say that detailed satellite monitoring, strict limits on further dredging, and stronger regional conservation efforts are essential if the remaining reefs are to avoid long-term collapse.

The study was published in Scientific Reports.