As millions of people worry about their rising electric bill, Elon Musk is looking up. Over the Martin Luther King Jr weekend, the Tesla CEO said the company will bring back its shelved Dojo3 chip project and turn it into AI7, a new generation designed for space-based AI compute that would power orbital data centers instead of Earth-bound server farms.

At first glance, it sounds like something out of a sci-fi movie. Yet it taps into a very real problem, since the rapid rise in artificial intelligence is colliding with power grids that are already under stress. OpenAI chief executive Sam Altman has warned that future AI systems will need an energy breakthrough and could consume far more electricity than people expect, pointing toward nuclear fusion or much cheaper renewables as the only way to keep up.

From scrapped supercomputer to space bet

The announcement marks a sharp U-turn for Tesla. In August 2025 the company decided to streamline its chip program and disband its in-house Dojo supercomputer team, shifting engineers toward more conventional AI5 and AI6 chips and relying more heavily on outside suppliers such as Nvidia. That move came after key leaders left and some former Tesla staff launched their own startups focused on AI hardware.

Even without Dojo, Tesla has been building an ambitious internal chip roadmap. Its AI5 generation, produced by foundry partner TSMC, is expected to power the company’s Full Self Driving system and the Optimus humanoid robot. AI6 chips are tied to a $16.5 billion supply agreement with Samsung, which will manufacture them at its Taylor, Texas facility for use in vehicles, robots and data center training workloads.

Now Musk wants to add a very different piece to that puzzle. In his updated roadmap, AI6 supports Optimus and conventional data centers, while AI7, also called Dojo3, is being redesigned specifically for space-based AI compute. Tesla has begun recruiting engineers again, asking candidates to email a dedicated address and share the three toughest technical problems they have solved, a sign that the company is trying to rebuild expertise it had only recently let go.

Why push AI training above the clouds

So why run AI in orbit instead of inside a warehouse next to a substation on the edge of town? The basic pitch is simple. A satellite in a sun-synchronous orbit spends nearly all day in sunlight, which means solar panels can deliver steady power without clouds, nighttime dips or heat waves that strain the local grid. In theory, a cluster of AI servers in space could run flat out without forcing utilities to keep old fossil fuel plants alive just to feed the latest chatbot or driving model.

That idea fits into a broader global scramble to find dedicated clean power for the AI boom. In the United States, projects like Data City in Texas promise multi-gigawatt campuses that sit behind the meter and generate their own energy for data centers, partly through green hydrogen, instead of leaning on public transmission lines. Ecoticias has already reported on those hydrogen megaprojects, which aim to solve the same bottleneck Musk is talking about, only from the ground up instead of from orbit.

There is a reason this matters to more than chip engineers. Studies and regulators in the United States warn that as AI tools and data centers multiply, the national grid is starting to show fracture lines, with higher bills, delayed power plant closures and renewed interest in burning fossil fuels to keep servers running.

In earlier coverage, Ecoticias highlighted how the US grid is beginning to creak under AI demand, and how companies are racing to build new clean energy sources fast enough to avoid large-scale blackouts.

Engineering hurdles and new environmental risks

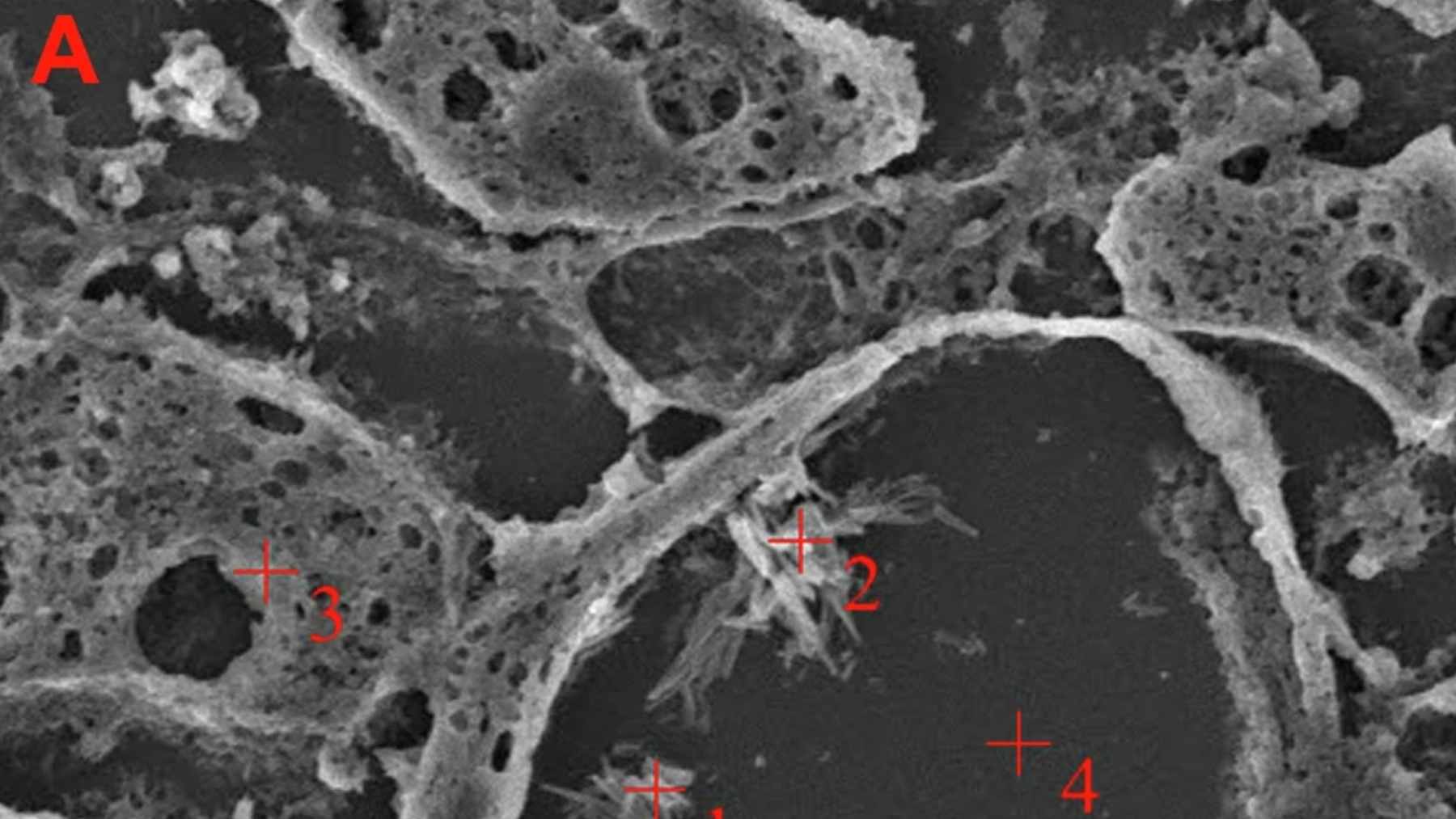

Turning satellites into floating supercomputers is not as easy as bolting some GPUs onto a Starlink platform. Space hardware has to survive intense radiation, which can flip bits inside chips and crash systems unless every component is carefully hardened. Getting rid of heat is another major challenge, because there is no air in space to carry warmth away, only radiators that glow their heat out into the void.

On top of that, AI training needs huge volumes of data, which means any orbital data center would rely on extremely high bandwidth optical or radio links to send and receive information from Earth.

Specialists interviewed by outlets such as Via Satellite say that, for now, the economics of full-scale data centers in space remain speculative and are likely to start with narrow uses such as batch training for defense or intelligence workloads rather than everyday consumer apps.

Musk himself has suggested that space-based AI might become cheaper than terrestrial options within four or five years, but that depends on Starship launches working reliably, satellites lasting long enough in orbit and solar hardware hitting aggressive cost targets.

From an environmental point of view, the story is complicated. On one hand, running AI servers from constant solar energy in orbit could, in theory, reduce the need for new gas or coal plants that keep humming all night to feed data centers.

On the other hand, every AI satellite has to be manufactured, launched and eventually deorbited, adding to the traffic in already-crowded orbits and contributing to the growing debate around space debris and orbital pollution, a topic European agencies have started to frame as a new kind of environmental crisis.

Competition on the road and in orbit

Musk’s renewed interest in custom chips also comes at a moment when the competition is heating up. At CES 2026, Nvidia introduced Alpamayo, a family of open models, datasets and tools designed to help carmakers build safer, reasoning-based autonomous vehicles without starting from scratch. For Tesla, whose Full Self Driving software has long depended on a closed, vertically integrated stack, an open rival makes the race for high performance and energy efficient AI even more intense.

Meanwhile, other technology giants are attacking the same energy puzzle from different angles. Google, for example, has signed an enhanced geothermal energy deal in Nevada to supply round the clock clean power for its data centers, a move Ecoticias covered in detail in its story on Google’s search for “energy for millennia”.

And in Texas, several projects marketed as solutions to a looming internet collapse promise tens of gigawatts of dedicated power for AI heavy infrastructure, as described in reports on Data City and the risk of an overworked digital backbone.

For everyday life, the question is simple, even if the engineering is not. Will these experiments in hydrogen deserts, geothermal wells and now orbital platforms actually make AI cleaner and more affordable, or will they just push the problem out of sight? The answer will show up not only in climate statistics, but also in the form of future electric bills, grid stability and the amount of junk we leave circling our planet.