It’s hard to drop anything through the air and have it land exactly where you want. A grocery bag slips off the passenger seat and rolls under your brake pedal, a paper airplane zags into a ceiling fan, and a “gentle toss” turns into a bank shot off the couch.

Now scale that problem up to a drone trying to deliver water or medicine, where “close enough” can still mean “wrong roof.” Engineers in Montreal say a new parachute design can make drops far more predictable, using nothing more complicated than a thin plastic sheet with carefully placed cuts. In tests, the design repeatedly fell almost straight down instead of drifting sideways.

How can a flat plastic disc turn into a parachute in midair?

The concept comes from Polytechnique Montréal in Montreal, Quebec, led by professors David Mélançon and Frédérick Gosselin, with collaborators including engineers at École Polytechnique in France. Instead of a fabric canopy with cords and seams, the team starts with a thin plastic disc and lets airflow do the “opening.”

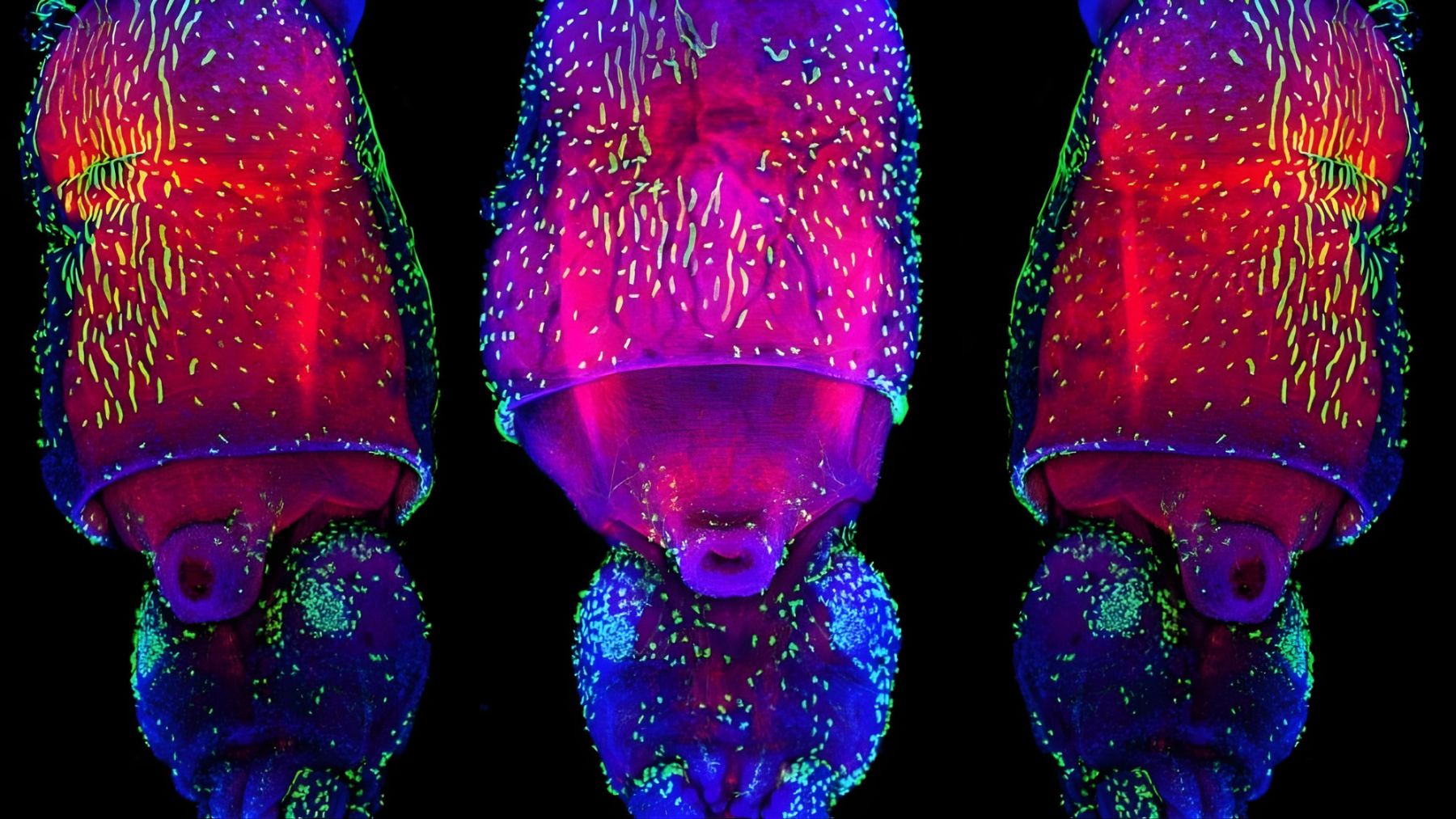

They used kirigami, a Japanese cutting technique that changes how a sheet bends and stretches. In simple terms, they laser-cut a closed-loop pattern into a Mylar disc and attach a small weight at the center. As it falls, the disc puffs into an inverted-bell shape, forming a stable canopy without traditional rigging.

Why do most parachutes drift, and what makes this one fall straight?

Typical parachutes can wander because crosswinds and uneven deployment create sideways forces, and the payload can swing like a pendulum. The kirigami cuts add porosity, meaning air can pass through, and flexibility, meaning sections of the disc can shift until forces even out.

The team describes this as flow-induced reconfiguration, basically a shape change caused by moving air. Once the motion calms down, the system reaches terminal velocity, the steady falling speed when air resistance matches weight. The key trade-off is a bit of speed for a lot more control, so the drop stays closer to vertical even when release angles and wind conditions vary.

How accurate was it in lab tests and in drone drops outside?

In lab comparisons, researchers tested three Mylar discs: one uncut, one with many concentric slits, and one with the closed-loop pattern. Only the closed-loop design stabilized quickly and repeatedly landed within about three feet of a target when dropped from 54 feet, including in gustier indoor and outdoor conditions.

They also ran wind-tunnel tests and outdoor drops using a drone carrying a water bottle from about 200 feet. The parachute settled into a steady descent with little sideways drift and no pitching, even when released off-level. “It will always realign and then fall straight down,” said Mélançon.

In a 54-foot indoor test that varied release angles from 0 to 45 to 90 degrees, the landing spread stayed small, making aiming simpler for tight drop zones.

How could a low-cost, no-fuss parachute change aid drops and deliveries?

Traditional parachutes can be expensive and delicate, which limits how widely they’re used for humanitarian airdrops or drone delivery, according to the Nature paper.

This design is just a single sheet that can be laser-cut or die-cut, clipped to a single suspension line, and deployed without the usual “fold-it-just-right” routine that feels suspiciously like wrestling a fitted sheet.

Less drift can mean fewer lost packages when winds shift mid-drop. For aid groups, that can translate into more supplies arriving where people are waiting, and fewer risky retrievals from rivers, roads, or rough terrain.

Because the system is pattern-based, it can also be adapted for different payload weights by adjusting cut spacing and count, rather than redesigning an entire canopy.

What’s next, and what are the limits today?

The researchers see a path to slower descents by covering the slits with a soft, stretchy film, increasing drag without losing the self-aligning behavior.

They also point to ballistic descent trajectory, meaning a mostly straight path set by gravity and the initial release, as something engineers can tune with new patterns.

With asymmetric cuts, future versions might spiral gently or glide before settling, adding a kind of steering without motors. Still, the current designs are meant for small loads and short drops, not people or high-altitude entries.

The team also notes that testing in thinner air, such as high mountains and Mars-like environments, would be part of exploring where this simple approach works best.

What can you do with this information if you work with drones, logistics, or emergency response?

For most readers, this is not a shopping item, but it is a “watch this space” tech if you care about deliveries, disaster response, or public procurement.

If you’re in an organization that moves supplies through the air, the practical question is whether straighter drops can reduce losses, liability headaches, and re-delivery costs. Here are a few concrete next steps:

- Track follow-up publications and field demonstrations tied to the Polytechnique Montréal team and the Nature paper.

- If you manage drone or relief operations, evaluate where “landing accuracy” is the bottleneck, such as tight urban drop zones or windy terrain.

- For public agencies and nonprofits, ask vendors how they measure drift and landing spread, not just “it opened.”

- For educators, consider the design as a safer way to teach drag, stability, and terminal velocity with small, low-energy drops.

If the work scales the way early tests suggest, the biggest win may be boring in the best way: fewer lost packages, fewer do-overs, and fewer “it landed somewhere over there” moments.

The work was reported by Polytechnique Montréal on Oct. 1, 2025, and published in Nature the same day.

Photo credit: LM2.