If you have ever heard that Earth will “soon” switch to 25-hour days, the key word you should question is soon. Scientists do expect Earth’s rotation to keep slowing down, but the change is so gradual that it is invisible in everyday life.

Still, the idea is real, and it comes down to a simple tug-of-war between Earth and the Moon. The same forces that move ocean tides also act like a tiny brake on the spinning planet, adding time to the day one sliver at a time.

A “day” is not as fixed as it sounds

Most of us learn that a day is 24 hours, because that is how we run school schedules, work shifts, and the alarm clock. But if you measure Earth’s spin using distant stars instead of the Sun, you get a slightly shorter value called a sidereal day, explained in simple terms by NASA’s Space Place.

That difference is not a mistake, it is just two ways of measuring motion. Earth is turning while also moving around the Sun, so the planet has to rotate a bit more for the Sun to appear in the same spot in the sky again.

And here is the bigger point: even the 24-hour “solar day” is not perfectly constant. It wobbles by tiny amounts, and over very long stretches of time it trends longer.

The Moon is the main reason Earth’s rotation slows

Earth’s oceans bulge because of the Moon’s gravity, creating tides that rise and fall as the planet spins. But the tidal bulges do not line up perfectly with the Moon, because the oceans and seafloor create friction, and that friction steals a little rotational energy from Earth.

A clear, official walkthrough of this process is described in NASA’s eclipse and Earth rotation explainer. In practical terms, Earth’s spin slows down, and the Moon slowly drifts farther away as the system trades energy.

If that sounds abstract, picture pushing a spinning office chair with your foot lightly dragging on the floor. The chair keeps turning, but it gradually loses speed.

How scientists can tell the planet is slowing down

You cannot feel Earth losing a tiny fraction of a second over a lifetime. So how do researchers know it is happening? They compare extremely precise clocks with astronomical observations and long historical records, including old eclipse timings.

Modern timekeeping also tracks small mismatches between clock time and Earth’s rotation. That is why organizations like the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service publish official bulletins tied to Earth orientation and timing.

On the clock side, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) explains how leap seconds have been used to keep global time close to Earth’s rotation. The U.S. Naval Observatory posts public leap-second announcements that show how closely timekeepers watch the planet’s spin.

So when would Earth reach a 25-hour day?

This is where headlines can get sloppy. There is no calendar date anyone can circle. The best-known estimates point to a timescale on the order of about 200 million years, assuming the Earth-Moon system keeps evolving in broadly the same way.

One line of research behind this discussion comes from a University of Toronto team, highlighted in an official explainer from the University of Toronto Faculty of Arts and Science. Astrophysicist Norman Murray is one of the researchers connected to this work on how Earth’s day length has changed over deep time.

So yes, the 25-hour day is “on the timeline.” But it is so far off that it will not affect humans, civilization, or even the shape of our calendars in any practical sense.

Other forces can nudge day length too

Tides are the long, slow drumbeat, but they are not the only influence. Earth’s rotation can shift slightly when mass moves around the planet, like when ice melts or large amounts of water redistribute.

That link between climate-driven mass changes and Earth’s spin is discussed in a NASA overview of rotation changes tied to ice and groundwater. These effects still operate on tiny scales, but they show the day length is shaped by more than one process.

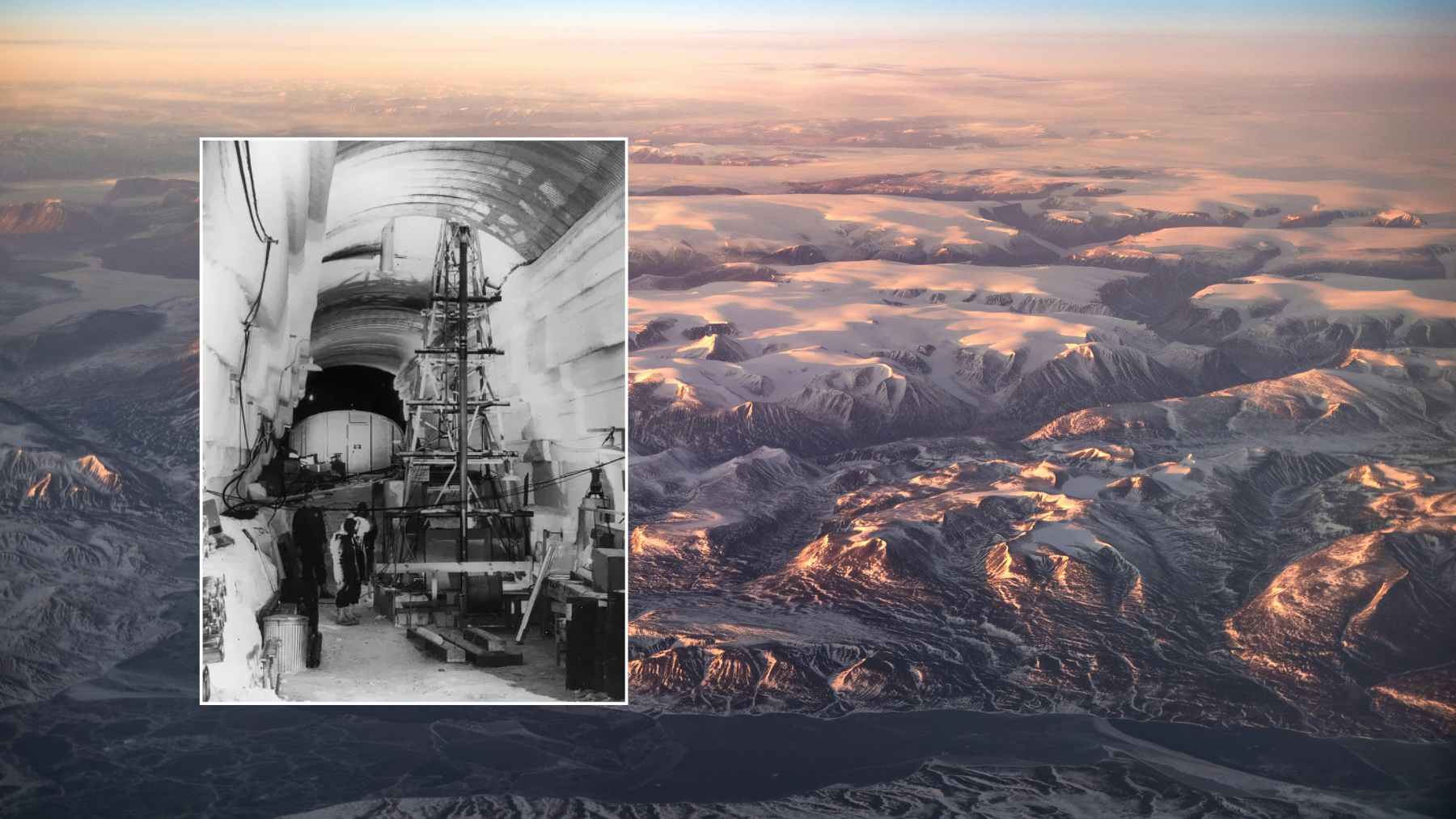

Even big engineering projects can have a measurable impact in theory, which is why some readers connect this topic to stories like this ECOticias report on a project linked to Earth’s rotation. It is a reminder that, at high precision, Earth is not a perfectly rigid spinning top.

The main study discussed here has been published in Science Advances.