Solar panels are usually sold with 25 to 30 years of performance promises. But what happens after that, when the warranty language is long gone and you are still hoping your roof system keeps shrinking the electric bill?

A new analysis led by Ebrar Özkalay at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts of Southern Switzerland suggests the answer can be surprisingly good. Looking at six solar arrays in Switzerland that have been running since the late 1980s and early 1990s, the team found most panels still produced more than 80% of their original power after three decades.

What the researchers tested, and what “aging” means for solar

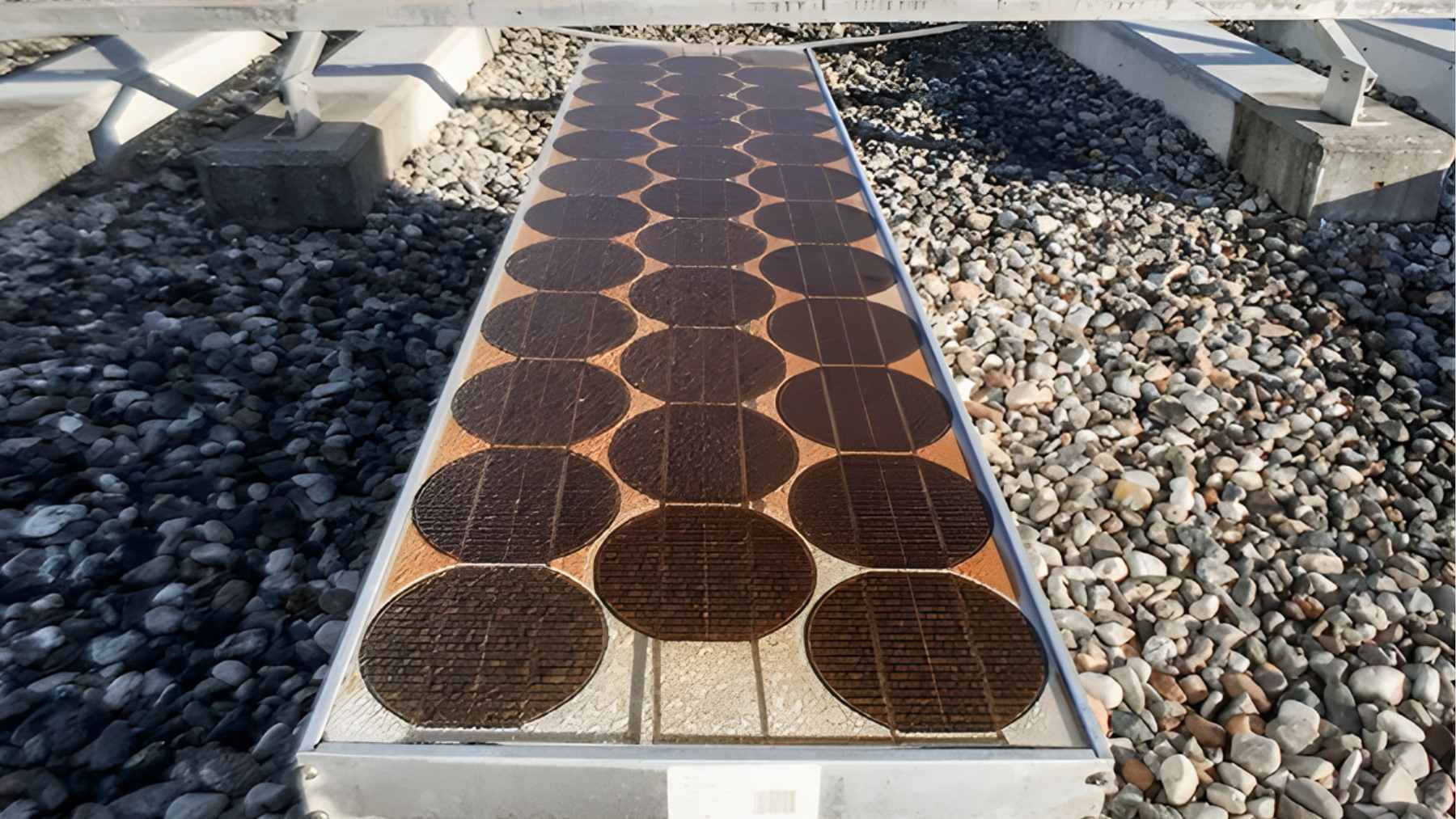

The scientists examined six grid-connected solar systems installed between 1987 and 1993 across different Swiss regions, from lower elevations to alpine sites. They combined decades of performance monitoring with lab tests on selected modules to see how output changed and what physical wear looked like inside the panels.

One key metric was the performance loss rate, which is basically how much power a system loses year by year as it ages. Across the six sites, the average annual loss was about a quarter of a percent, far lower than the range often cited in earlier field studies. In plain terms, that is slow aging.

Heat, altitude, and the “ingredient list” inside a panel

Why did some systems do better than others? Temperature turned out to be a major character in the story. The study reports that lower-altitude systems faced higher thermal stress, with module temperatures reaching about 20 degrees Celsius warmer than high-altitude sites, and those hotter panels tended to degrade faster.

The team also zoomed in on the materials that make up a module, sometimes called the bill of materials, meaning the full “ingredient list” of components. Think of it like buying sneakers. Two pairs can look similar, but the glue, stitching, and rubber quality decide what happens after years of heat, moisture, and daily wear. In this case, the study found clear differences tied to material quality, even within the same module family.

Some of the wear mechanisms were very specific but easy to picture. The encapsulant, the clear plastic layer that helps protect and hold the solar cells, showed more breakdown in hotter conditions, and the researchers linked that to chemical byproducts that can contribute to corrosion over time.

How this compares with earlier solar longevity research

Long-term real-world datasets are rare, which is why studies like this carry extra weight. Many durability expectations still lean heavily on accelerated aging tests, where panels are stressed in chambers to simulate years of sunlight, heat, and humidity in a shorter time. The Swiss team argues that decades of outdoor data help ground those assumptions in reality.

Earlier long-run work has often found faster average decline. For example, a 2015 National Renewable Energy Laboratory paper on a 20-year-old silicon system reported degradation around eight-tenths of a percent per year, which is more in line with older “rule of thumb” numbers.

That does not mean every panel will cruise past 30 years. The Swiss authors stress that climate, mounting setup, and manufacturing choices all shape outcomes, and they caution that their results are most representative of temperate and alpine Central European conditions, not every environment on Earth.

Why it matters for households, the grid, and public health

For homeowners, the practical takeaway is simple. If well-built panels keep producing useful power for decades beyond the usual warranty window, the long-term economics can look better than many people assume, especially once installation costs are already paid off. And yes, that can mean more years of quieter monthly bills.

Policy and incentives can still change the math, sometimes abruptly. In the United States, the IRS says the Residential Clean Energy Credit is not available for property placed in service after December 31, 2025, under recent law changes, which puts more emphasis on the long-run performance of systems that are already installed.

There is also a public-health angle that is hard to ignore. Replacing fossil-fueled electricity with cleaner sources helps reduce air pollution, and the World Health Organization links air pollution to millions of premature deaths each year.

The main study has been published in EES Solar.