Scientists have pushed the direct chemical record of life on Earth back to at least 3.3 billion years, using artificial intelligence to read faint molecular traces trapped inside ancient rocks from South Africa. The same work finds molecular hints that oxygen-producing photosynthesis was already active at least 2.5 billion years ago, roughly 800 million years earlier than previous chemical evidence showed.

That may sound like distant, abstract history. Yet those tiny early microbes helped build the oxygen-rich air you breathe on the way to work and shaped the climate that still cushions our planet today.

How AI learned to read stone

The international team, led by researchers at the Carnegie Institution for Science, examined 406 samples that included modern plants and animals, fungi, fossil coals and shales, meteorites, synthetic laboratory organics, and very old sediments from Earth’s early crust.

Each sample went through a technique called pyrolysis gas chromatography mass spectrometry. In simple terms, the rock is gently baked until its organic matter breaks into thousands of tiny fragments. Those fragments are separated and weighed, creating a complex chemical fingerprint that would look like a dense barcode to human eyes.

Instead of hunting for a few well-known molecules, the scientists fed entire fingerprint patterns into supervised machine learning models known as random forests. The AI was trained on samples whose origins were already known, then asked to decide whether unknown rocks carried organic matter from life or from non-biological processes such as meteorites or laboratory chemistry.

According to the team, the models correctly separated biogenic from abiogenic samples in more than 90 percent of tests and sometimes reached about 98 percent accuracy in modern materials. They also distinguished photosynthetic from non-photosynthetic life with about 93 percent success.

As co-author Robert Hazen put it, the system is “like showing thousands of jigsaw puzzle pieces to a computer and asking whether the original scene was a flower or a meteorite.”

Life and early photosynthesis in deep time

Once trained, the AI turned to some of Earth’s oldest carbon-rich rocks. It found strong biogenic signals in 3.33 billion year old sediments from the Josefsdal Chert in South Africa’s Barberton Greenstone Belt.

Those chemical patterns do not preserve whole molecules such as fats or pigments. Instead, they reveal statistical regularities in how fragments cluster together, which for the most part differ from the more random suites seen in meteorites and synthetic mixtures. That is what allowed the models to say that these fragments are much more likely to come from ancient cells than from non-living chemistry.

The team also detected molecular signatures consistent with photosynthetic life in rocks from the 2.52 billion-year-old Gamohaan Formation in South Africa and in the roughly 2.3 billion-year-old Gowganda Group in Canada.

Previous work had only found clear chemical fossils of photosynthesis in rocks younger than about 1.7 billion years, so this result almost doubles the time window in which molecular traces still carry usable ecological information.

If photosynthesis was already established by that time, it fits with independent evidence that Earth’s atmosphere was beginning to gain oxygen during the so-called Great Oxidation Event. That shift eventually built the protective ozone layer, changed ocean chemistry, and laid the groundwork for complex plants and animals.

Why an ancient trick matters for today’s planet

Seen through an environmental lens, this story is about planetary engineering carried out by microbes over unimaginable spans of time. Early photosynthetic communities slowly pulled carbon dioxide from the air, locked some of that carbon into rocks and buried organic matter, and released oxygen that transformed the surface environment.

Much later, humans began digging up part of that buried carbon as coal, oil, and gas. In practical terms, we are now burning in a couple of centuries what took ancient ecosystems millions of years to tuck safely underground.

Understanding how the earliest biosphere interacted with the atmosphere and oceans helps scientists refine models of long-term climate stability, which in turn informs how risky our current fossil fuel habits really are.

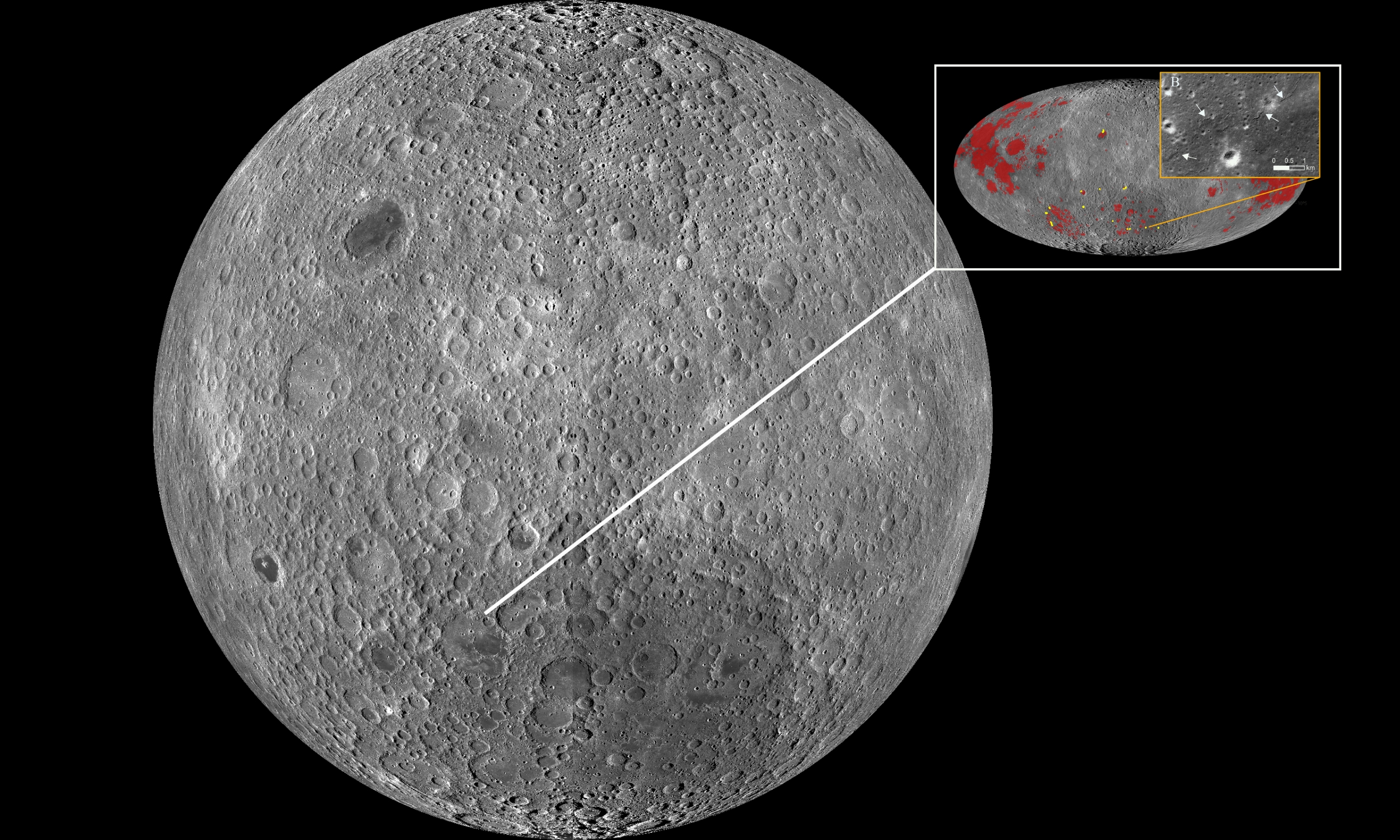

The new method also matters for worlds beyond Earth. The same combination of detailed chemistry and AI pattern recognition could be applied to samples from Mars or from icy moons such as Europa or Enceladus, where any surviving organics are likely to be heavily altered by radiation and time.

At the end of the day, the message is careful but hopeful. Ancient rocks that look almost featureless to the naked eye still hold “chemical echoes” of long-vanished ecosystems. If we learn to read those echoes here, we may someday recognize them on another world and better understand how life and climate entwine on our own.

The study was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Credit image: NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University and Tom Watters, Smithsonian Institution.