Anyone who has walked along a beach and watched tiny ridges form where waves lap the shore has seen a simple bit of physics in action. Now the same kind of pattern, frozen into Martian rock, is giving scientists some of the clearest proof yet that Mars once held shallow, ice-free lakes of liquid water.

A new analysis of delicate “wave ripples” captured by NASA’s Curiosity rover in Gale Crater shows that billions of years ago, wind-driven waves stirred the surface of a standing lake on the red planet. At the time, Mars must have been warm enough, and its air thick enough, to keep that water from instantly freezing.

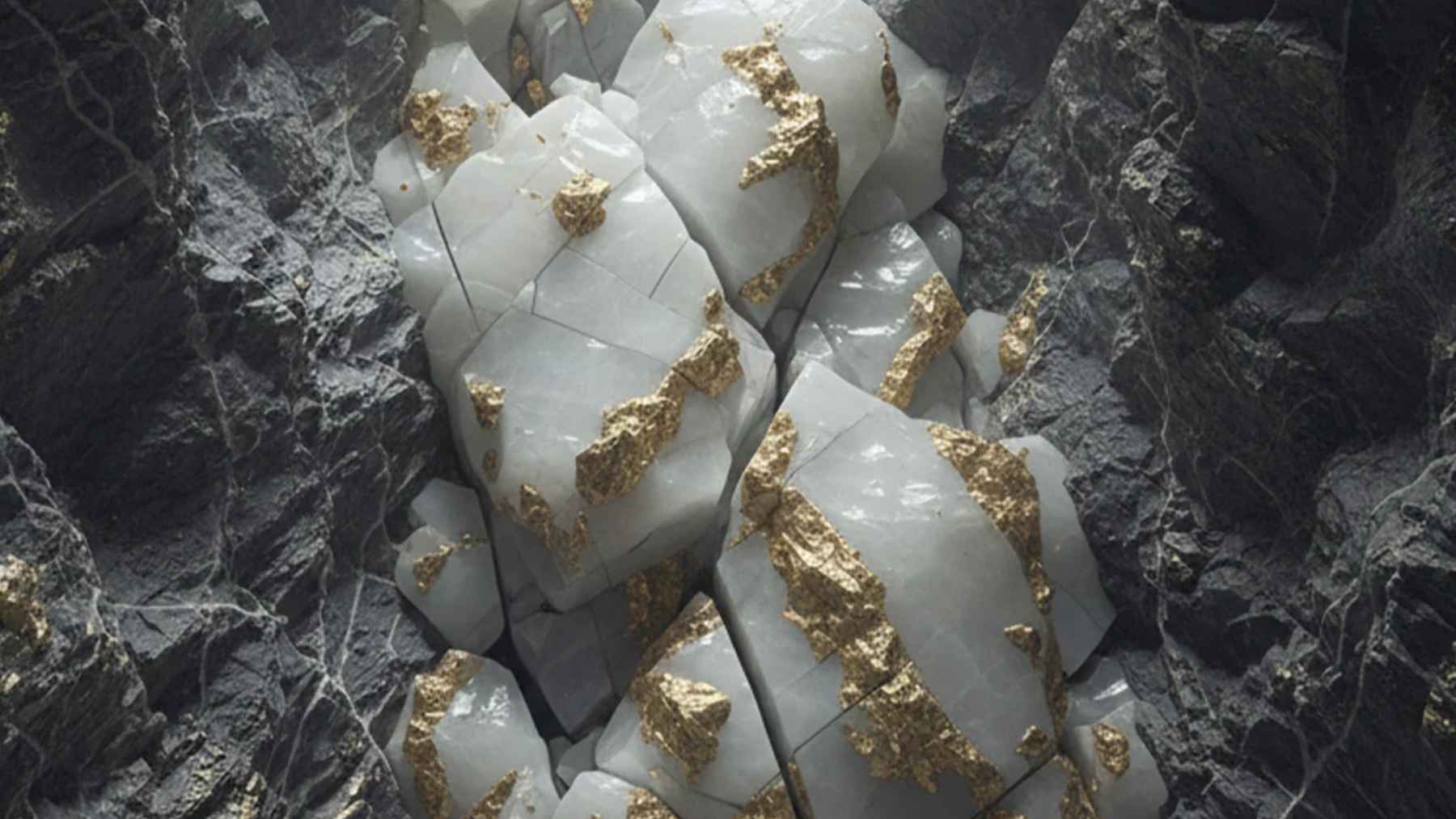

Ripples that only waves can draw

The features in question are small, symmetrical ripples that run in neat, parallel lines through a thin band of rock. Geologists recognize that shape from Earth. It forms when gentle waves move back and forth over a lake bed, nudging sand and silt until they stack up into tiny crests.

“The shape of the ripples could only have been formed under water that was open to the atmosphere and acted upon by wind,” explains Claire Mondro of the California Institute of Technology, lead author of the new study in the journal Science Advances.

The team dates the ripples to roughly 3.7 billion years ago, a period when many models suggested Mars was already becoming colder and drier. Their very existence hints that open water lingered longer than expected on the surface.

Reading a lake from millimeter high ridges

Up close, the ripples are surprisingly small. Curiosity’s cameras show ridges only about six millimeters high, spaced four to five centimeters apart. Using computer models that link ripple size to water depth, co-author Michael Lamb estimated that the ancient lake was no deeper than about two meters.

That would make it a broad, shallow body of water, something like an oversized pond spread across the floor of Gale Crater. The ripples appear in at least two rock layers, including a thin, erosion resistant bench known as the Amapari Marker Band, which circles part of the crater’s interior.

These outcrops were first photographed by Curiosity in late 2022 as the rover climbed the lower slopes of Mount Sharp. Only later did detailed analysis reveal that the patterns were the most unambiguous wave ripples ever seen on another world.

A warmer and wetter Mars than expected

Symmetrical wave ripples do more than prove that water once stood here. They also act as a climate test. For this kind of pattern to form, the lake surface has to stay liquid and exposed to the air so that wind can raise waves. If an ice lid had sealed the lake, the ripples would not exist in this form.

That has big implications for early Mars. The result suggests a thicker atmosphere and milder temperatures than some earlier climate calculations allowed. John Grotzinger, a geologist at Caltech and former project scientist for the Curiosity mission, calls it “an important advance for Mars paleoclimate science,” noting that the rover had already found evidence for long lived lakes back in 2014 and has now shown that some of those waters were free of ice.

In other words, Mars did not jump straight from warm and wet to the hyper arid desert we see today. There was a drawn out middle chapter when small lakes still shimmered under an open sky.

What this means for life and future explorers

Water is a key ingredient for life as we know it, so every extra chapter in Mars’s watery history matters. As Mondro puts it, “Extending the length of time that liquid water was present extends the possibilities for microbial habitability later into Mars’s history.”

If tiny microbes ever made a home in Gale Crater, a shallow, wave-stirred lake would have been a promising place. Constant mixing would deliver nutrients and keep temperatures relatively even, just as happens in small lakes on Earth.

For upcoming missions, these rippled rocks are more than a curiosity. They highlight specific layers where future rovers, landers, or even human crews could hunt for chemical traces of ancient life and for buried ice or hydrated minerals that might one day help supply drinking water and oxygen. In practical terms, that means past shorelines and lake beds are moving higher on the Martian wish list.

For climate scientists, the discovery also turns Mars into a kind of cautionary tale. Here is a planet that once had lakes and perhaps even an ocean, yet somehow lost most of its air and surface water over time. Understanding that story helps researchers better frame how atmospheres evolve, including our own.

All of this insight comes from ripples no taller than a grain of rice. They sat undisturbed on Mars for billions of years, waiting for a rover’s camera and a careful team of scientists. It makes you wonder what other quiet clues to planetary climate and habitability are still hiding in the rocks of the red planet.

The study was published in Science Advances.