For barely ten seconds in March 2025, a burst of high-energy light slammed into the detectors of a new space mission. That flash began its trip almost 13 billion years ago, when the universe was young, and astronomers now know it came from the earliest confirmed supernova ever seen.

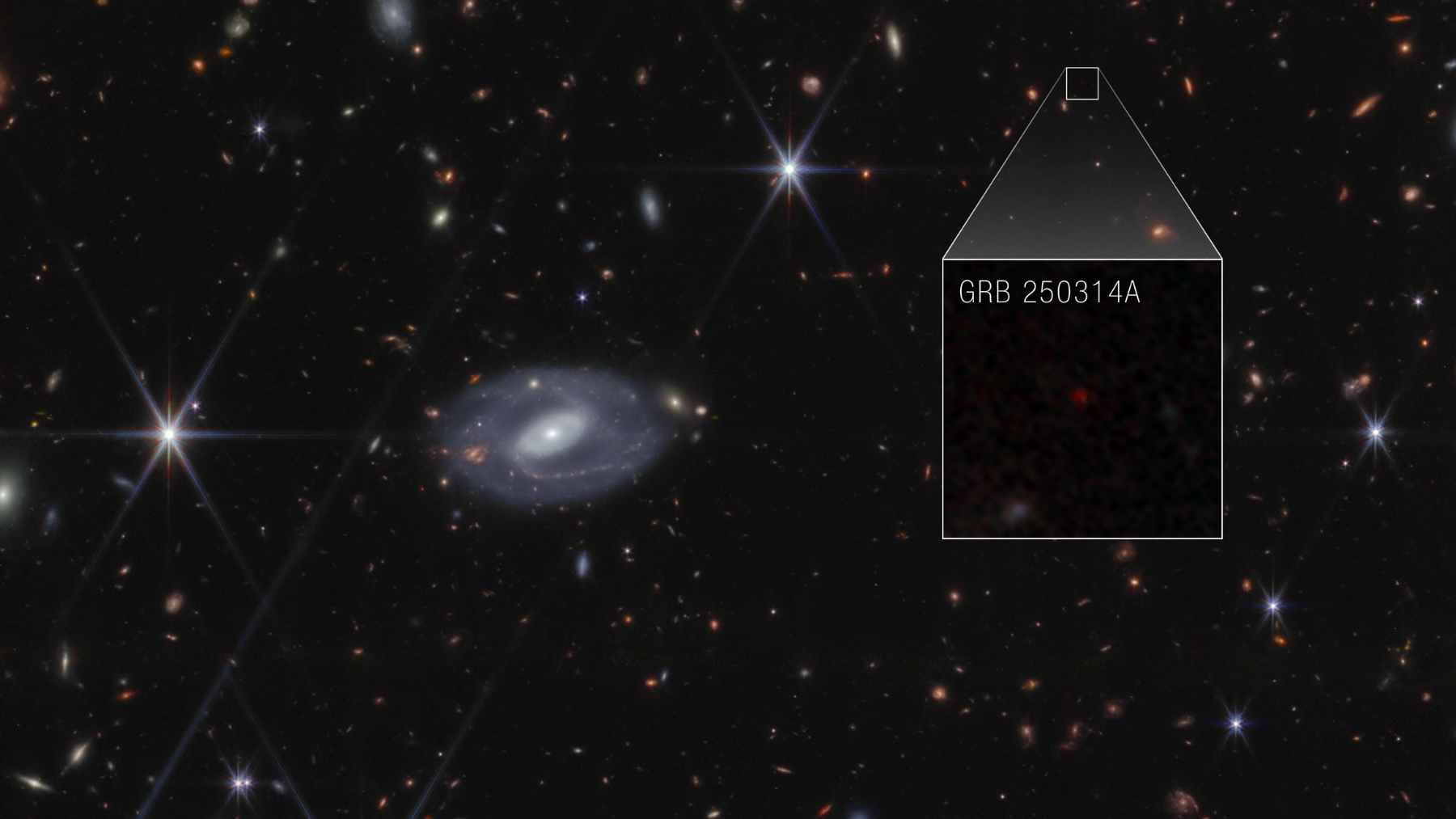

Using the James Webb Space Telescope and ground based observatories, an international team traced the signal, called GRB 250314A, to a massive star that exploded when the universe was about 730 million years old.

A cosmic alarm from the reionization era

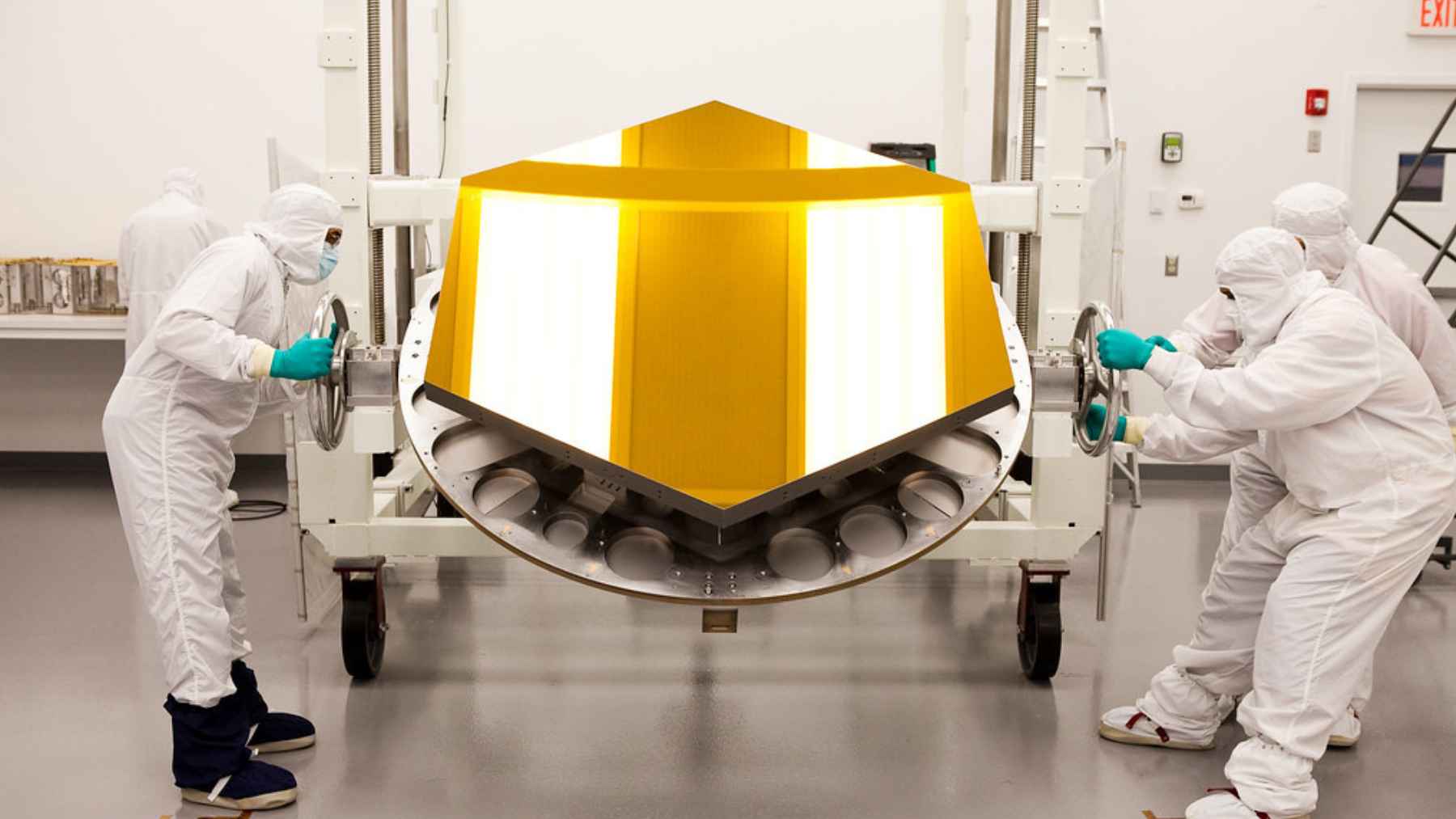

The story starts with SVOM, a Franco-Chinese satellite designed to spot sudden high-energy events in the sky. On March 14, 2025 its instruments recorded a long gamma-ray burst lasting around ten seconds, a classic sign that a very massive star had just collapsed.

Within about ninety minutes, NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory pinned down the position, and telescopes in the Canary Islands and at the Very Large Telescope in Chile measured how much the light had been stretched by the expansion of space. That stretch pointed to a redshift of about 7.3, meaning the explosion happened when the universe was only around 730 million years old, during the era when the first galaxies were clearing away a fog of hydrogen gas.

From gamma-ray burst to record supernova

A gamma-ray burst is the opening act in this kind of stellar death. The initial spike fades fast, but the shattered star can keep brightening as a supernova, then slowly dims.

Because GRB 250314A sits so far away, cosmic expansion stretched its light in color and in time so that an evolution that would take weeks in a nearby galaxy unfolded over several months in our telescopes. That gave astronomers a rare chance to schedule a deep follow up instead of racing the clock.

On July 1, 2025, the James Webb Space Telescope turned its near infrared camera on the source. Webb’s crisp images separated the glow of the supernova from the faint smudge of its host galaxy and confirmed that a single massive star had blown itself apart in the early universe.

An ancient explosion that looks familiar

Many models predicted that the very first generations of stars would explode in unusual ways, far more extreme than the supernovae we see nearby. This blast did not follow that script.

The team led by Andrew Levan of Radboud University found that the brightness over time and the spectral fingerprints of this event look strikingly similar to those of well-studied supernovae linked to gamma-ray bursts in the modern universe.

“Webb showed us a supernova that behaves much like nearby ones,” said astronomer Nial Tanvir of the University of Leicester.

Measurements show that the explosion behind GRB 250314A closely resembles classic gamma ray burst supernovae such as SN 1998bw rather than some exotic early universe event. That suggests that in at least some galaxies, massive stars were already living and dying in fairly familiar ways less than a billion years after the Big Bang.

Why this matters back on Earth

Events like this sit in a very small club. In roughly fifty years of observations, only a handful of gamma-ray bursts have been traced to the universe’s first billion years, so each one becomes a powerful probe of how the first stars formed and exploded.

For daily life, none of this will change tomorrow’s weather forecast or cut anyone’s electric bill. Yet it quietly reshapes the story of our own planet. The iron in blood, the calcium in bones, and the metals in solar panels and smartphones were all forged in earlier generations of stars, then spread through young galaxies by explosions like the one behind GRB 250314A.

In practical terms, this ten-second flash has given astronomers a new way to study how and when the first heavy elements were made and how quickly the young universe assembled the ingredients for planets and life.

The press release was published by “NASA Science”.