High on a wooded hillside in Abruzzo, a small stone house now sits in silence. Until a few weeks ago it was home to Nathan Trevallion, Catherine Birmingham and their three children, who lived with solar panels, well water, a composting toilet and a vegetable patch far from town.

After the Juvenile Court in L’Aquila removed the children from the home, that off-grid experiment turned into a national and international storm. Judges said the minors were unschooled, isolated and living in unsanitary conditions, while the parents insist they chose a healthier life in nature.

At the center of the case lies a simple question that touches many families who dream of unplugging from the system. How far can you go before the state steps in to protect children?

The Abruzzo case that split Italy

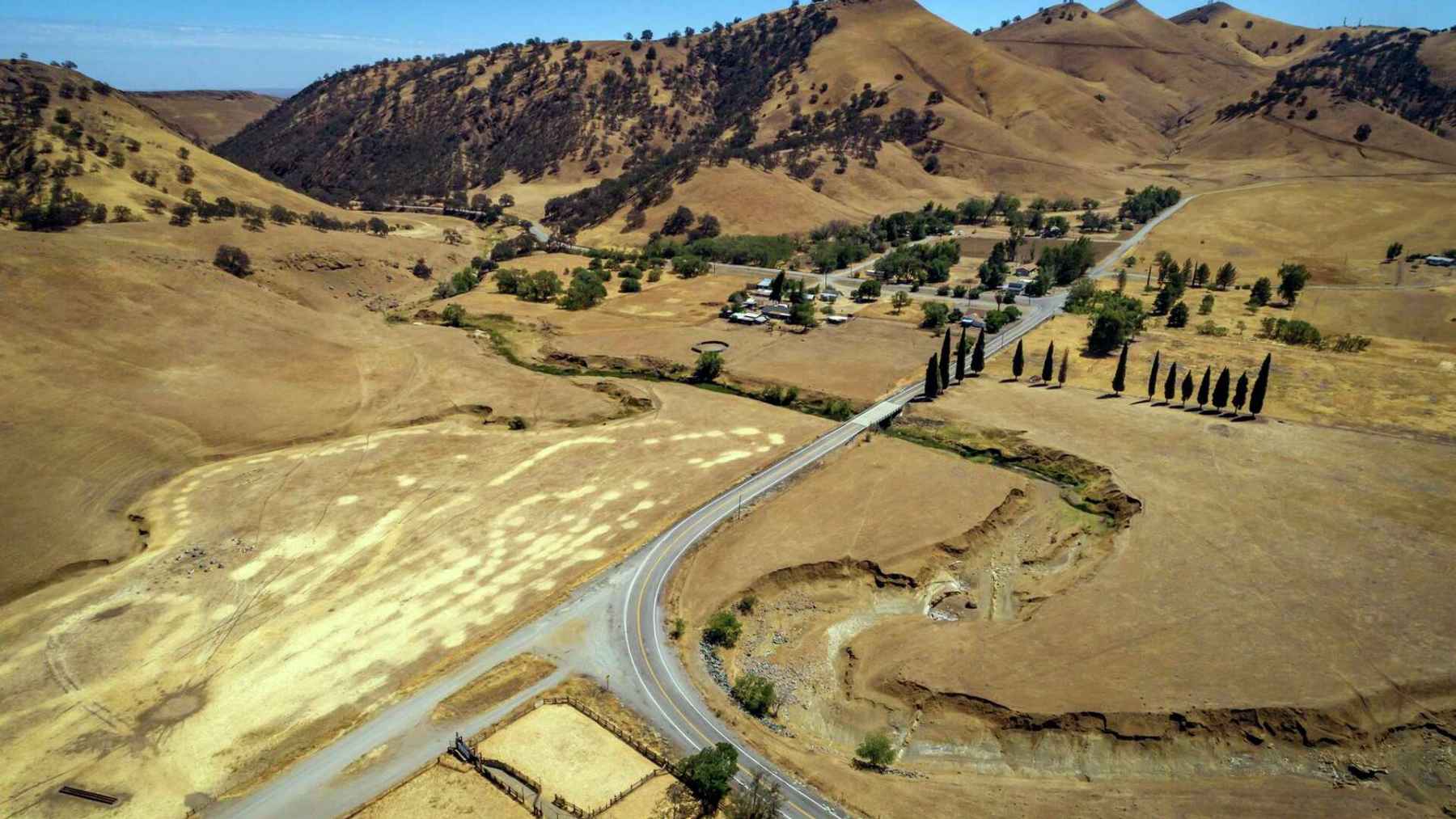

Since 2021 the Anglo-Australian couple had lived with their three children in woodland near Palmoli, a hilltop village in eastern Abruzzo. Their stone farmhouse relied on solar panels for limited electricity, a well for water and an outdoor dry toilet instead of indoor plumbing.

Italian daily Corriere della Sera described the building as precarious and reported that the children did not attend local school or regular pediatric checkups.

In autumn 2024 the family were hospitalized after accidentally eating poisonous mushrooms, an incident that triggered inspections by social services and police. Their reports concluded that the house lacked basic sanitation and that the children were being educated only through informal unschooling at home, without clear monitoring by the authorities.

In November 2025 the Juvenile Court ordered the three minors into a protection center and suspended the parents’ custody, allowing the mother to stay with the children while the father remained alone in the forest home.

The parents, who say they followed Italian rules for home education, called the decision “a great injustice” and announced plans to appeal. Around 140,000 people signed online petitions backing the family, while politicians including Matteo Salvini and Giorgia Meloni publicly criticized the court, prompting magistrates’ groups to warn against political pressure on judges.

What began as a dispute over one rural house now serves as a test case for how far a country like Italy will tolerate off grid lifestyles when minors are involved.

Off-grid living moves from niche to mainstream

At its simplest, living off grid means cutting or reducing ties to public utilities such as power lines, water networks or sewage systems and relying instead on solar panels, wells, wood stoves and gardens.

Ideas magazine Ethic describes how social networks now overflow with videos of families drying their own food, people renovating camper vans and couples spending half the year living off the land they cultivate and forage. Off grid has become not only a way to ease an electric bill or escape traffic noise, but also a lifestyle and even a kind of emotional brand of disconnection.

That dream can carry politics too. Ethic notes that a small current within the movement overlaps with so-called sovereign citizen groups that deny the authority of the state, although most off-grid projects grow from concerns about sustainability, telework, climate anxiety or fear of social and economic collapse.

Communities such as Tamera in Portugal openly prepare for possible breakdowns of the current model, while governments in Sweden and Finland distribute preparedness guides that tell households to stock food, water and backup sanitation for days of crisis.

In other words, the wish to depend less on fragile systems is no longer fringe. The Abruzzo family simply pushed that impulse to a point where it collided directly with child welfare rules.

Spain off-grid boom under clearer rules

Spain has quietly become one of the European countries where off-grid living is spreading fastest, helped by abundant sun, rural depopulation and relatively affordable land in areas such as Catalonia, the Alpujarra mountains or other interior regions.

English language media describe a wave of British, German and Dutch families buying old farmhouses to install solar panels, dry toilets and rainwater systems while chasing lower living costs and more time outdoors.

Alongside them, long-standing eco villages such as Matavenero, Lakabe and Arterra Bizimodu have helped repopulate abandoned hamlets with projects centered on sustainability and communal self management.

On paper, Spanish energy rules are relatively friendly to this kind of autonomy. A national rule known as Real Decreto 244/2019 regulates self consumption and accepts homes that generate their own electricity with solar panels, batteries or small generators as long as installations follow safety standards set by the Ministry for the Ecological Transition.

In practical terms that allows a family to live with standalone solar power and never sign a contract with a utility company, especially if they register the system to access public subsidies or specialized insurance.

Water is more tightly controlled. Spain’s water framework treats most underground supplies as part of the public hydraulic domain, so drilling a new well or increasing extraction normally requires authorization from the relevant river basin authority, and using groundwater without the right paperwork can result in serious fines.

Put simply, a rural family can drink from its own well, but the intake has to be recorded and kept within legal limits.

Housing and schooling draw an even sharper line. While planning rules allow people to live in remote houses that meet basic safety and sanitation standards, education law obliges all children from 6 to 16 to follow recognized schooling, and Spanish courts have already sanctioned parents who removed their children from the system to teach them at home.

Homeschooling remains effectively unregulated, so families who ignore official enrollment can face truancy cases, social services visits and, in serious disputes, the sort of judicial intervention now seen in Italy.

Freedom, children and the limits of the off-grid dream

For many European families the appeal of the countryside is easy to understand, trading crowded trains, high rents and constant notifications for clean air and a garden. The Italian forest family shows that moving off grid does not automatically break any law, yet it can clash with norms about hygiene, documentation and, above all, children’s rights when taken to the limit.

At the end of the day, the fight in Abruzzo is less about solar panels or dry toilets and more about who decides whether a child is safe and properly educated.

In Spain and other countries, the most stable projects tend to mix autonomy and public services, with families who grow their food and harvest rainwater but also register their homes, vaccinate their kids and send them to the village school.

That hybrid model may lack the radical purity some dream of, yet it keeps the state mostly at bay and gives children more choices later in life. It is a compromise, which might be the real price of freedom when minors are involved.

In a world full of screens, noise and monthly bills, it is not hard to see why some parents head into the hills looking for another way to live.

The main report on this case has been published by Corriere della Sera.