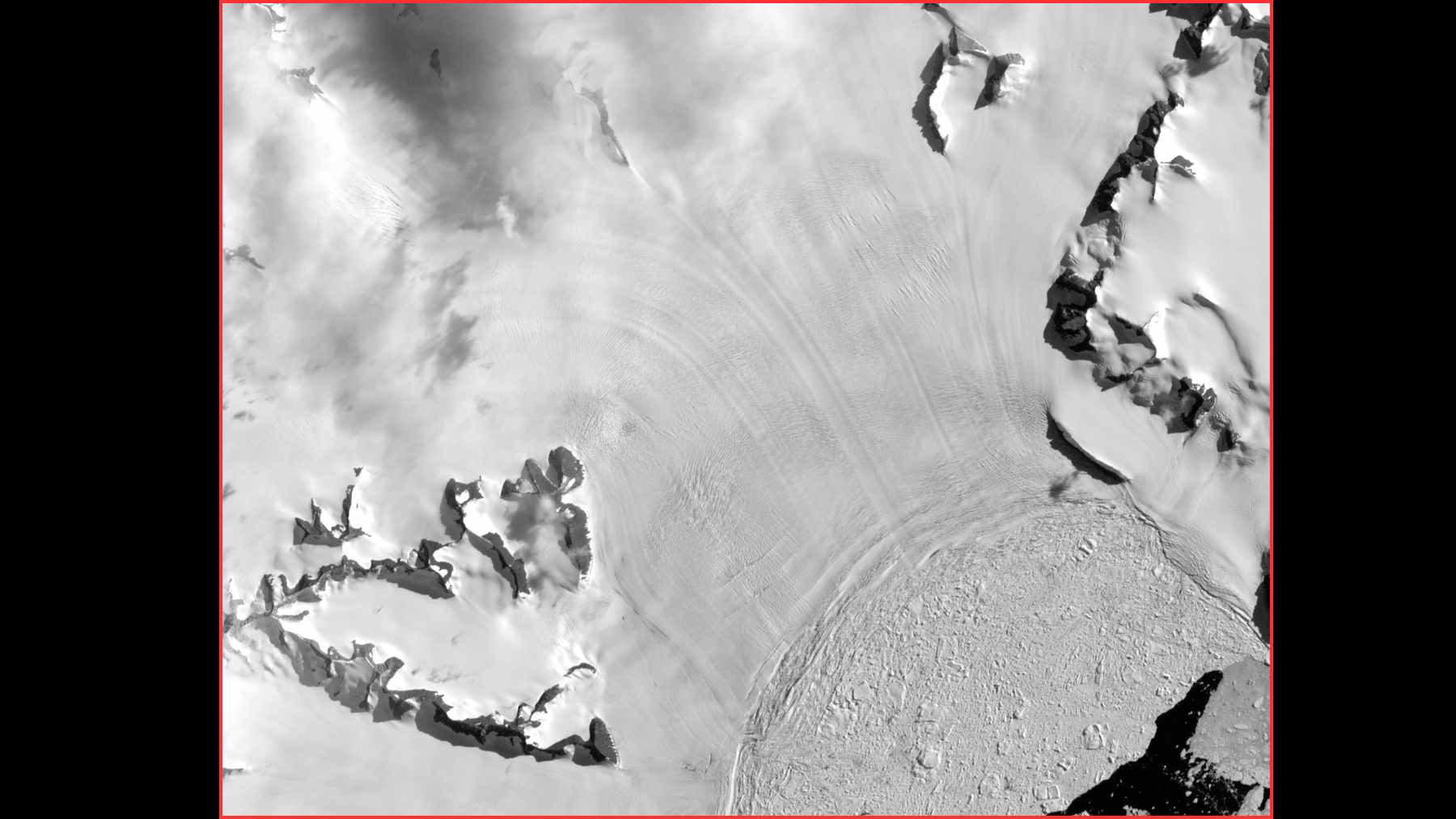

A remote glacier on the eastern Antarctic Peninsula has done something researchers had only really seen in computer models and in reconstructions from the end of the last Ice Age. In just two months in late 2022, Hektoria Glacier retreated about 8 kilometers and lost nearly half its length, the fastest grounded glacier retreat ever recorded in modern history.

Grounded glaciers usually creep backward a few hundred meters in a year. Hektoria pulled back that much in a single day. The new analysis, led by scientists at the University of Colorado Boulder and published in Nature Geoscience, estimates a peak retreat rate of roughly 0.8 kilometers per day between November and December 2022, nearly ten times faster than any previously measured value for a glacier that still rested on the seabed.

For sea level, Hektoria itself is small. For what it tells us about how quickly larger glaciers might fail, it is a wake up call.

A collapse that unfolded almost by accident

Researchers were already watching the bay in front of Hektoria because of a band of “fast ice” there. This is sea ice locked to the coast that can act like a natural brace for nearby glaciers. In 2011 the bay filled with this fixed ice, which helped stabilize Hektoria and neighboring glaciers and allowed them to push forward into the bay as thick floating tongues.

That quiet phase ended in 2022. When storms and warm ocean water broke up the fast ice, waves could finally reach the glacier front. Within months, satellite images showed the glacier thinning, speeding up and then disintegrating in a rapid series of calving events. Between January 2022 and March 2023, Hektoria’s front retreated roughly 25 kilometers, with the most dramatic loss packed into those two months at the end of 2022.

The collapse was not obvious at first. One of the study’s authors has described noticing the change almost by chance while checking routine satellite data. What they saw sent them back through radar, elevation and even seismic records to reconstruct what happened.

The hidden ice plain under Hektoria

The key to this sprint backward lies under the ice. Hektoria does not sit on a steep rocky slope. It rests on what glaciologists call an ice plain, a broad, relatively flat area of soft sediment below sea level near the point where ice transitions from grounded to floating.

As the glacier thinned under attack from warm ocean water, more of this buried plain became buoyant. Once enough ice lifted off the seabed, water was able to force its way into crevasses and under the front of the glacier. Large slabs then broke away in quick succession in a process known as calving.

One scientist likened the sequence to a line of dominoes that tips backward instead of forward, each newly exposed block of ice becoming vulnerable as the previous piece peels off. The result is not a gentle retreat but a sudden jump.

Seismic stations in the region recorded earthquake-like signals during this period, consistent with massive icebergs snapping off a glacier that was still at least partly grounded. That detail matters because only grounded ice contributes directly to sea level rise when it moves into the ocean.

Climate change and a polar hotspot

This extreme event did not happen in a vacuum. The Antarctic Peninsula is one of the fastest warming regions on the planet, with temperatures that have risen more than three degrees Celsius since the 1950s, several times faster than the global average.

Warmer air and ocean water have helped shrink sea ice around Antarctica in recent years, including around the peninsula. When sea ice and fast ice vanish, waves can travel farther, battering glacier fronts that were once shielded. In the case of Hektoria, scientists say the break up of coastal sea ice and the arrival of relatively warm water in the bay likely primed the glacier for failure by accelerating thinning and weakening that ice plain base.

To a large extent, this is what climate models have been warning about. Warmer oceans quietly undermine ice from below long before dramatic images of calving cliffs show up in the news.

Why a “small” glacier matters for coastal cities

On its own, Hektoria will not rewrite global sea level projections. Researchers emphasize that its total stored ice is modest by Antarctic standards.

The concern is what its behavior suggests about much larger glaciers that rest on similar ice plains. The Antarctic ice sheet as a whole holds enough frozen water to raise global sea levels by around 60 meters if it ever melted completely.

Even a tiny fraction of that, unleashed more rapidly than expected, would ripple through everyday life far from the polar circle, from higher coastal flood insurance bills to more frequent saltwater intrusion in farms and drinking water supplies.

The new study shows that a grounded glacier can jump backward at rates previously associated mostly with floating ice shelves or with the very end of the last Ice Age. That suggests today’s projections, which often assume relatively smooth retreat, may not fully capture the risk of sudden step changes in sea level if similar ice plain instabilities occur under bigger glaciers.

At the end of the day, what the researchers are really saying is that we still do not have a complete map of the weak spots under Antarctica. Ice plains have already been identified beneath other glaciers in Antarctica and Greenland.

The authors argue that mapping the bedrock beneath marine-terminating glaciers is now essential in order to understand where the next Hektoria-style collapse could happen and how it might affect future sea level rise.

For people living far from the poles, it can be tempting to see Antarctica as a distant white backdrop. Hektoria’s sudden retreat is a reminder that what happens on that frozen coastline will slowly, and sometimes abruptly, reshape our own.

The study was published in Nature Geoscience.