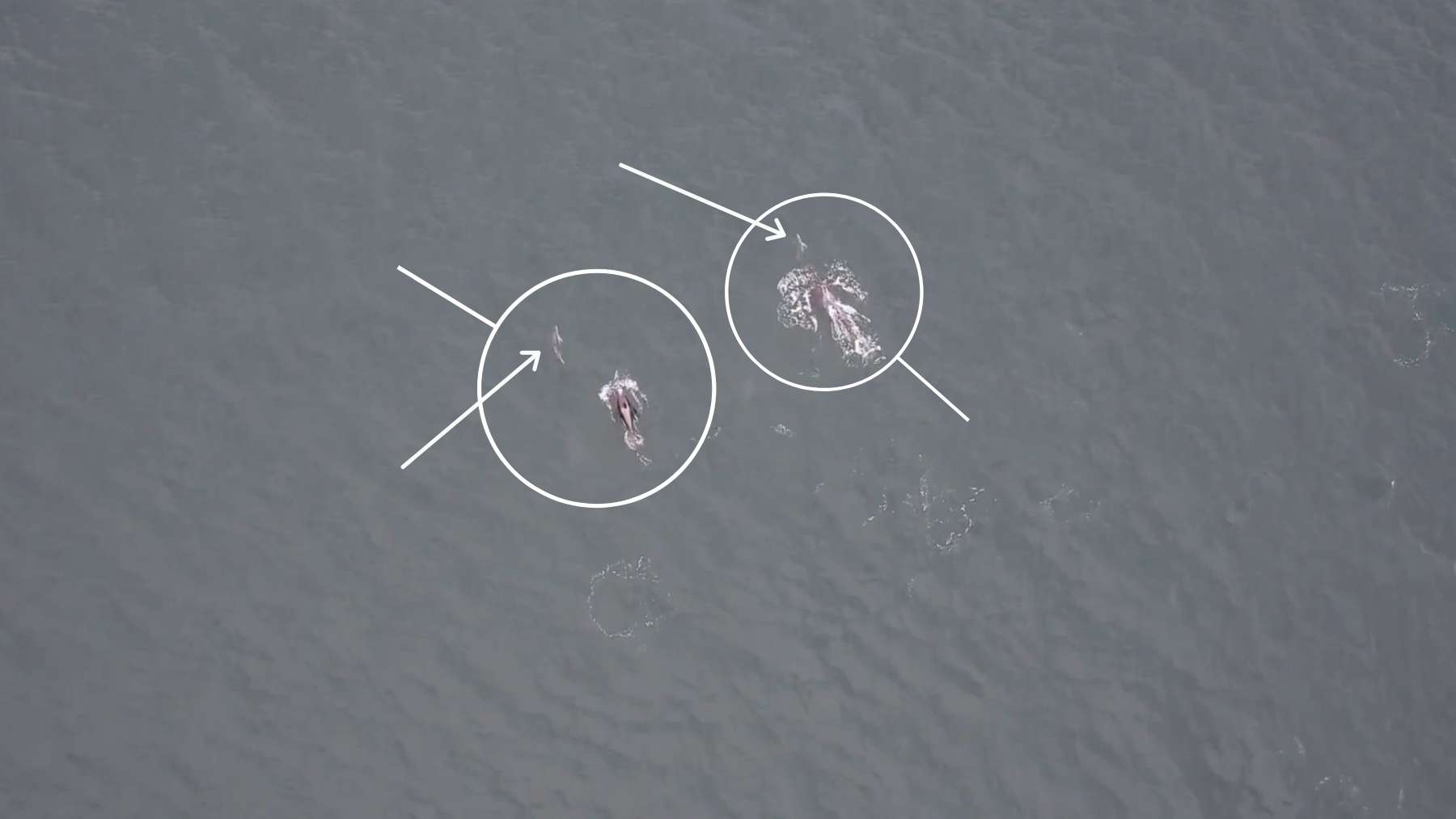

For the first time, scientists have filmed killer whales and dolphins apparently working together to hunt Chinook salmon off the coast of British Columbia. The footage and tag data point to a rare alliance between northern resident killer whales and Pacific white‑sided dolphins that could reshape how we see cooperation in the ocean.

An unlikely hunting partnership

The research team followed nine fish‑eating killer whales near Vancouver Island during two weeks in late summer, using drones, underwater cameras and multi‑sensor tags that recorded movement, sound and video. They saw dolphins swimming near the tagged whales again and again. In 258 encounters, the dolphins showed up only when the whales were searching for, catching or eating salmon.

Then came the surprises. On 25 occasions, whales that were headed one way suddenly veered off and followed the dolphins instead, diving alongside them toward deeper water where adult Chinook salmon lurk. So what persuaded these top predators to stop ignoring each other and start diving in sync?

Following dolphin sonar to hidden salmon

Killer whales rely heavily on sound to hunt. They send out echolocation clicks, listen for echoes from fish, then chase the targets. Pacific white‑sided dolphins do something similar but tend to move quickly and cover wide areas.

Tag recordings showed that when dolphins were nearby, the whales often quieted down. Their own echolocation dropped for stretches of the dive while the dolphins kept clicking ahead of them.

The study authors interpret this as a kind of acoustic hitchhiking. The dolphins sweep the water with sonar, the whales trail behind and listen in. Chinook salmon are large, fast and powerful, often too big for the dolphins to catch and swallow whole, yet they are the whales’ favorite meal.

In practical terms, it looks like this. Dolphins locate fish. Whales follow, grab a salmon, then carry it to the surface and break it into pieces for their own family pod.

Leftovers for the dolphins

The cooperation does not stop at detection. During eight recorded salmon kills, the whales tore fish apart and shared pieces with other whales in the group. Dolphins were present for half of those events. In one clear case, they swooped in to eat small fragments that drifted away from the whales’ mouths.

For the dolphins, that looks like a pretty good deal. They get access to chunks of high‑energy salmon that are finally small enough to handle. For the whales, the benefit seems to be better odds of finding those big Chinook in the first place.

Lead author Sarah Fortune summed it up this way. “Our footage shows that killer whales and dolphins may actually be cooperating to find and share prey, something never before documented in this population.”

No aggressive behavior showed up on the videos. No tail slaps, ramming or attempts to chase dolphins away, which you might expect if the smaller animals were simply stealing food.

Cooperation or clever freeloading

Not every expert is ready to stamp this as full‑blown teamwork. Some biologists point out that dolphins could still be acting as opportunistic “scroungers,” grabbing scraps while also enjoying safety by hanging near fish‑eating orcas instead of dolphin‑eating ones.

Others see the finely-tuned movements, the repeated course changes toward dolphins and the careful sharing of prey and argue that, to a large extent, the pattern fits classic cooperative foraging. The truth may sit somewhere in between. Nature rarely draws clean lines.

A fragile alliance in a stressed ocean

This story is not only about smart animals. It is also about a stressed ecosystem. Northern resident killer whales are listed as threatened in Canada, with only a few hundred individuals that depend heavily on adult Chinook salmon.

Those salmon have been squeezed by habitat loss, fishing pressure and warming rivers. When the big fish become harder to find, every hunting advantage matters. If whales are now leaning on dolphins as roaming sonar units, that hints at how finely-balanced their world has become.

Many of the same salmon runs that sustain this alliance also show up in human life, from sport fishing to the fillet in a grocery store. Add in ship noise, pollution and climate‑driven marine heatwaves, and you start to see why researchers are racing to understand every piece of the food web.

What we can take from two smart predators

For most of us, the closest we get to these animals is a distant fin on a whale‑watching trip or a nature documentary on the couch. Yet their new partnership carries a simple message. Ocean species are not just competing for survival. They are also solving problems together in ways we are only beginning to notice.

If two apex predators can adjust and cooperate in a changing sea, it puts a quiet question back on us. How quickly can we adjust our own habits so there is still enough wild salmon, clean water and quiet ocean space for them to keep doing it?

The study was published in Scientific Reports.

Official videos of the project.