What if the largest ocean linked to our planet is one you will never see on a map or from a beach? A team working with data from thousands of seismic stations has found evidence of an enormous reservoir of water about 700 kilometers beneath Earth’s surface, locked inside deep mantle rock and estimated to hold roughly three times as much water as all the surface oceans combined.

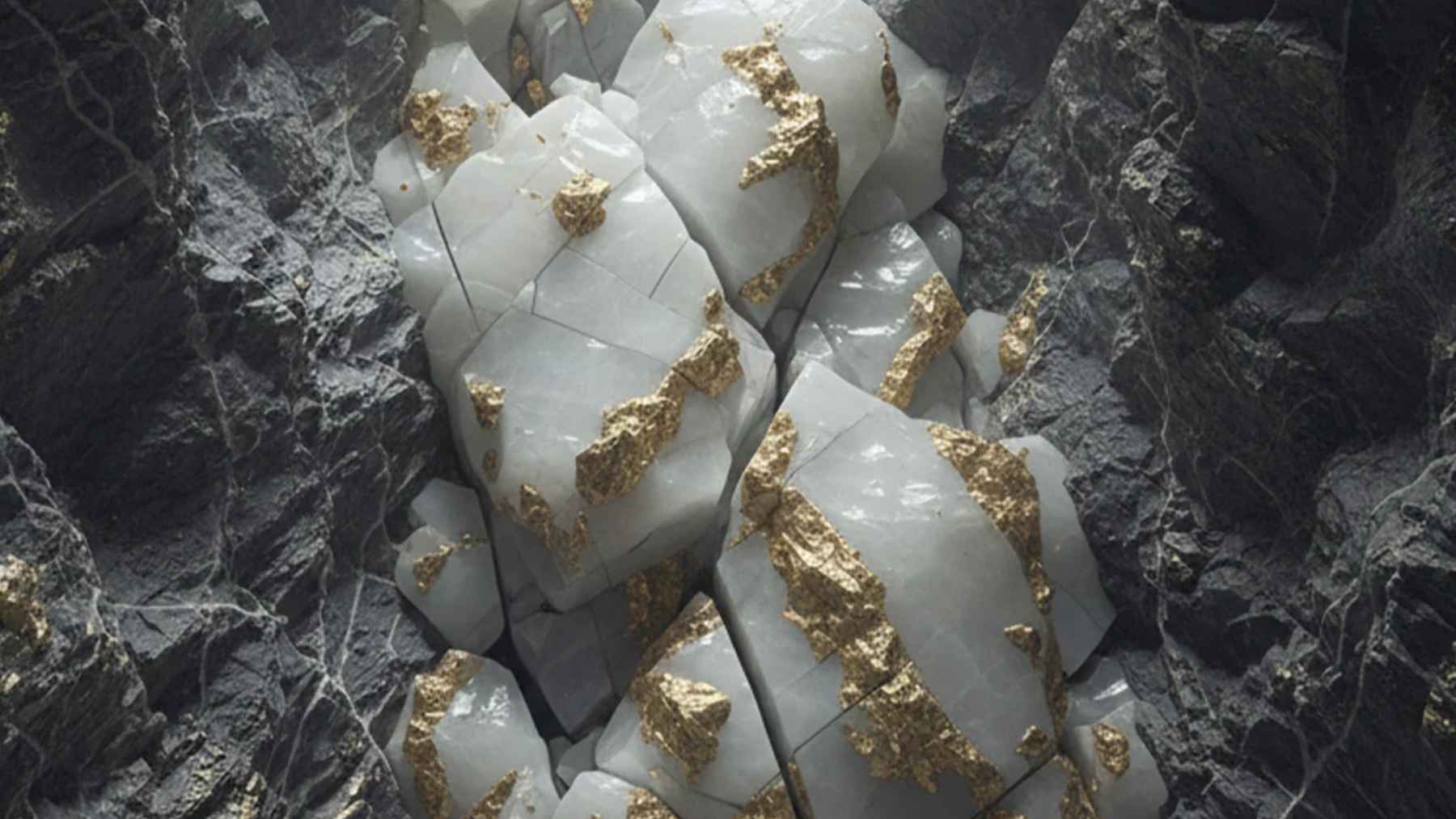

This underground store is not a free flowing sea. It sits inside a blue mineral called ringwoodite that forms under the extreme pressure of the mantle’s transition zone between the upper and lower mantle. In that zone, water is bound to the crystal structure of the rock at the molecular level, more like a planet-sized sponge than a buried lake.

Listening to earthquakes for clues

To uncover this hidden hydrosphere, researchers deployed about 2,000 seismographs across the United States and analyzed seismic waves from more than 500 earthquakes. As these vibrations travel through Earth’s interior, they speed up or slow down depending on what they pass through. In regions where the mantle rock is “wet,” the waves move more slowly. By mapping that slowdown, the team inferred a vast volume of water-rich ringwoodite around 700 kilometers down.

It is a bit like using the planet’s natural earthquakes as medical scans. Each tremor sends energy through the deep interior. Instruments at the surface record how that energy changes, revealing what lies between the crust we stand on and the core far below.

Evidence that water came from within Earth

The discovery feeds into a long running debate about where Earth’s water originated. For years, many scientists favored icy comets and water-rich asteroids as the main source. The new findings point in another direction.

Steven Jacobsen of Northwestern University, a lead researcher on the work, calls the deep reservoir “tangible evidence that water on Earth came from within.”

He and colleagues suggest that this hidden store helps explain why the volume of the oceans has remained relatively stable over hundreds of millions of years despite shifting continents and changing climates. Jacobsen has warned that without such a buffer, so much water could have reached the surface that “the water would be on the Earth’s surface, and mountaintops might be the only land visible.”

In other words, Earth appears to run a whole planet water cycle. Oceanic crust slides into the mantle at subduction zones, dragging surface water with it. In the transition zone, minerals such as ringwoodite soak up part of that water. Over geologic time, some of it returns to the surface through volcanic activity and mantle upwelling.

Rethinking the familiar water cycle

Most of us learn a simple version of the water cycle in school, with arrows connecting clouds, rain, rivers, and the sea. This work hints that the diagram should stretch far deeper beneath our feet. The “hidden ocean” shows that the atmosphere and surface oceans are only the visible part of a much larger system that extends hundreds of kilometers down.

That does not mean there is a new water source we can tap to fill reservoirs or ease droughts. The water is trapped inside minerals at crushing pressures and searing temperatures, far beyond any realistic drilling or extraction technology. What it does offer is context for why liquid water has persisted on Earth for billions of years and why our planet, unlike Mars or the Moon, still supports a global ocean and a thriving biosphere.

What scientists want to know next

For now, most of the seismic evidence comes from beneath North America. Researchers are eager to collect similar data from other regions to see whether water-rich ringwoodite is common worldwide or concentrated in particular zones. They also want to refine estimates of how much water the transition zone holds and how quickly it cycles in and out.

Those answers matter for more than satisfying curiosity. They will shape models of how Earth formed, how plate tectonics has operated over deep time, and how our familiar surface oceans have been sustained.

Next time you turn on the tap or watch waves roll in at the coast, it may be worth remembering that an even larger reservoir of water is probably hidden far below, locked in stone and quietly helping to keep our blue planet habitable.

The study was published on the Science website.