Scientists in South Korea have taken a new step toward turning star power into a practical energy source. Their KSTAR device, often called an artificial Sun, has held a cloud of super hot plasma at about 100 million degrees Celsius for 48 seconds and kept a high performance state going for more than 100 seconds after a major upgrade to its inner wall.

On paper that may not sound like much time. In fusion research, though, holding star-like heat for nearly a minute without destroying the machine is a big deal, especially when the goal is to build reactors that can one day feed clean electricity into homes and help bring down power bills and emissions at the same time.

In Europe, a related device known as WEST has already kept a slightly cooler plasma going for about six minutes in a fully tungsten lined chamber, showing that long runs in these extreme conditions are starting to look realistic instead of sci-fi.

What KSTAR just proved

KSTAR is a doughnut-shaped fusion device operated by the Korea Institute of Fusion Energy in Daejeon, with support from the National Research Council of Science and Technology. Officials there report that during its most recent campaign, the machine sustained an ion temperature of roughly 100 million degrees Celsius for 48 seconds and maintained a high confinement mode, a favored operating regime for power plants, for 102 seconds.

Those numbers matter because fusion on Earth needs higher temperatures than the real Sun. Our star fuses hydrogen at about 15 million degrees thanks to crushing gravity, while the thin plasma in a reactor has far lower density, so the particles must move much faster before they can collide and fuse. KSTAR’s team is now pushing toward a target of 300 seconds at similar temperatures in the second half of this decade, which would bring experiments closer to what a future power plant needs.

Why holding a tiny star is so hard

Fusion reactors work by turning gas into plasma, a state of matter where electrons are stripped from atoms and everything behaves like a hot, charged soup. No solid material can touch that soup at 100 million degrees, so powerful superconducting magnets wrap around the vessel to hold it in place, almost like an invisible bottle.

The problem is that this plasma is restless. It wiggles, ripples, and sometimes throws violent bursts of heat and particles toward the walls, events physicists call edge localized modes. KSTAR has become known for developing ways to tame these bursts with carefully tuned magnetic fields and control systems, which is one reason it has been able to stretch its high performance pulses into the tens of seconds range without losing stability.

Tungsten walls built to survive star heat

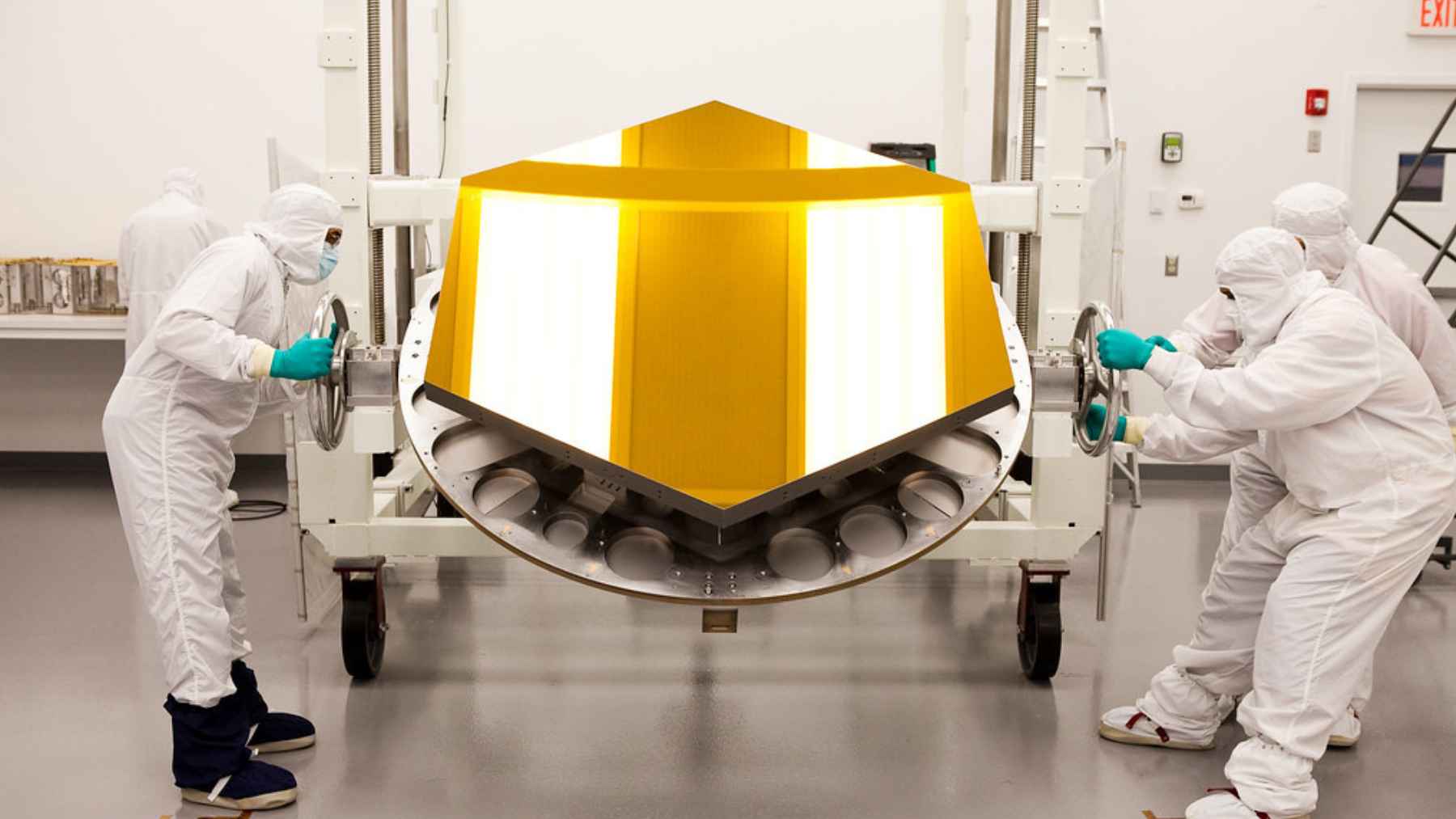

At the bottom of KSTAR’s vacuum chamber sits a component called the divertor, which acts like a high-tech exhaust. It funnels out waste gas, helium “ash,” and excess heat from the plasma and takes the brunt of the thermal load. Engineers recently replaced the old carbon divertor with one made from tungsten, a metal with the highest melting point of any element and a heat flux limit that can reach about 10 megawatts per square meter, similar to what a spacecraft sees during reentry.

Carbon turned out to behave a bit like a sponge, soaking up precious hydrogen fuel and especially tritium, which raises both safety and efficiency issues. Tungsten holds much less fuel and can cope better with the intense conditions that a commercial reactor would face.

The importance of this switch is not limited to Korea, since the WEST tokamak in France, clad entirely in tungsten, has already sustained a roughly 50 million degree plasma for about six minutes, proving that this tough metal can support very long pulses in practice.

A testbed for ITER and future reactors

KSTAR is not working in isolation. It serves as a pilot device for ITER, the huge international fusion project under construction in southern France that aims to be the first tokamak to produce a large net gain of fusion power. Insights from KSTAR’s long pulses, tungsten divertor behavior, and control techniques are feeding directly into design and operating choices for that much larger machine.

In an official statement on the latest record, KFE president Suk Jae Yoo called the result “a green light for acquiring core technologies required for the fusion DEMO reactor,” referring to the demonstration plants that are supposed to follow ITER and actually make electricity for the grid.

ITER itself is designed to reach even higher temperatures than KSTAR, but it will rely on many of the same ideas, from superconducting magnets to tungsten facing parts, that Korean scientists are stress testing right now.

The remaining roadblocks to fusion on the grid

For all the excitement, today’s fusion machines still do not give back more usable energy than they consume as full facilities. It takes a lot of electric power to cool the magnets close to absolute zero, run giant heating systems, and keep the control hardware and support equipment running, so the overall energy balance at the plug remains negative in devices like KSTAR.

Another challenge comes from the flood of fast neutrons created when deuterium and tritium nuclei fuse. These uncharged particles slam into the walls and slowly damage the crystal structure of metals, which can make components brittle over years of operation. Future power plants will also need so-called breeding blankets filled with lithium bearing materials, which react with these neutrons to make fresh tritium fuel, a process that ITER will test for the first time with dedicated blanket modules inside its vessel.

Why this progress still matters for everyday life

So why should anyone who is more worried about next month’s electric bill than plasma physics care about a 48 second record in a lab in Daejeon? The reason is that controlled fusion promises a source of steady, low-carbon power that uses tiny amounts of fuel, produces no greenhouse gases while it runs, and shuts itself off in an instant if something goes wrong because the plasma simply cools and fades away.

There are still decades of work ahead on materials, fuel cycles, and plant design, and experts regularly warn that fusion is not a quick fix for today’s climate problems. Even so, KSTAR’s latest performance, together with the six minute tungsten run in France, shows that holding a tiny artificial star inside a metal ring is no longer just a dream in computer models.