Black holes are famous for what they hide. In a new set of observations, astronomers say one of these objects gave itself away by tugging on the fabric of the universe, as Albert Einstein’s theory of gravity predicted.

The clue was a steady wobble, repeating about every 20 days, in the glowing wreckage of a destroyed star. The results were published on December 10, 2025, and they point to the clearest direct evidence so far that a spinning black hole can drag spacetime around with it.

A quick guide to “frame-dragging” in plain language

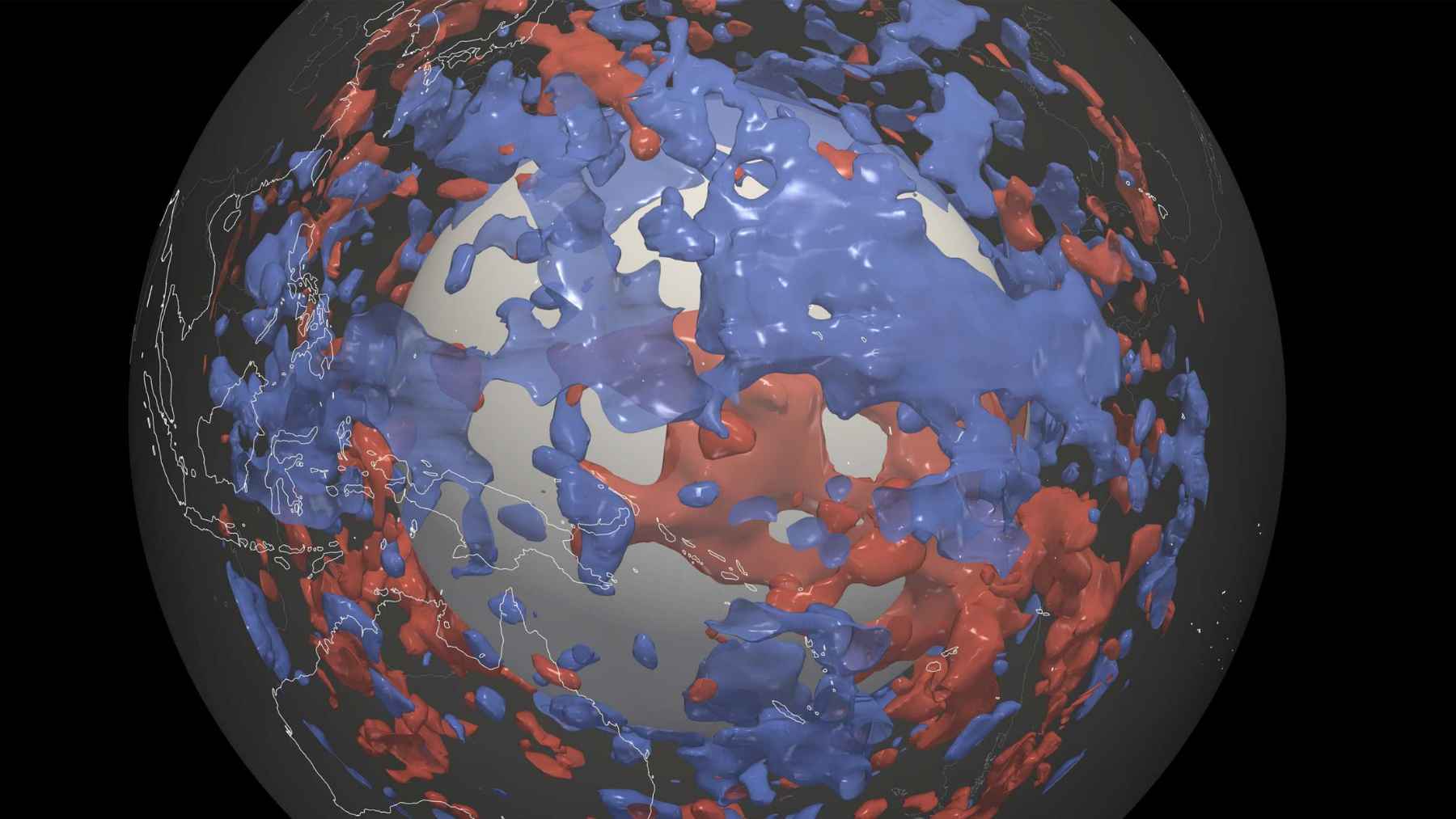

Spacetime is the idea that space and time are woven into one fabric, and gravity is what happens when that fabric bends. If a massive object spins, the theory says it should also twist the fabric nearby, like a top stirring thick honey.

That twisting is called Lense-Thirring precession, often described as frame-dragging. In practical terms, it can force nearby orbits to wobble, even when nothing physically pushes them.

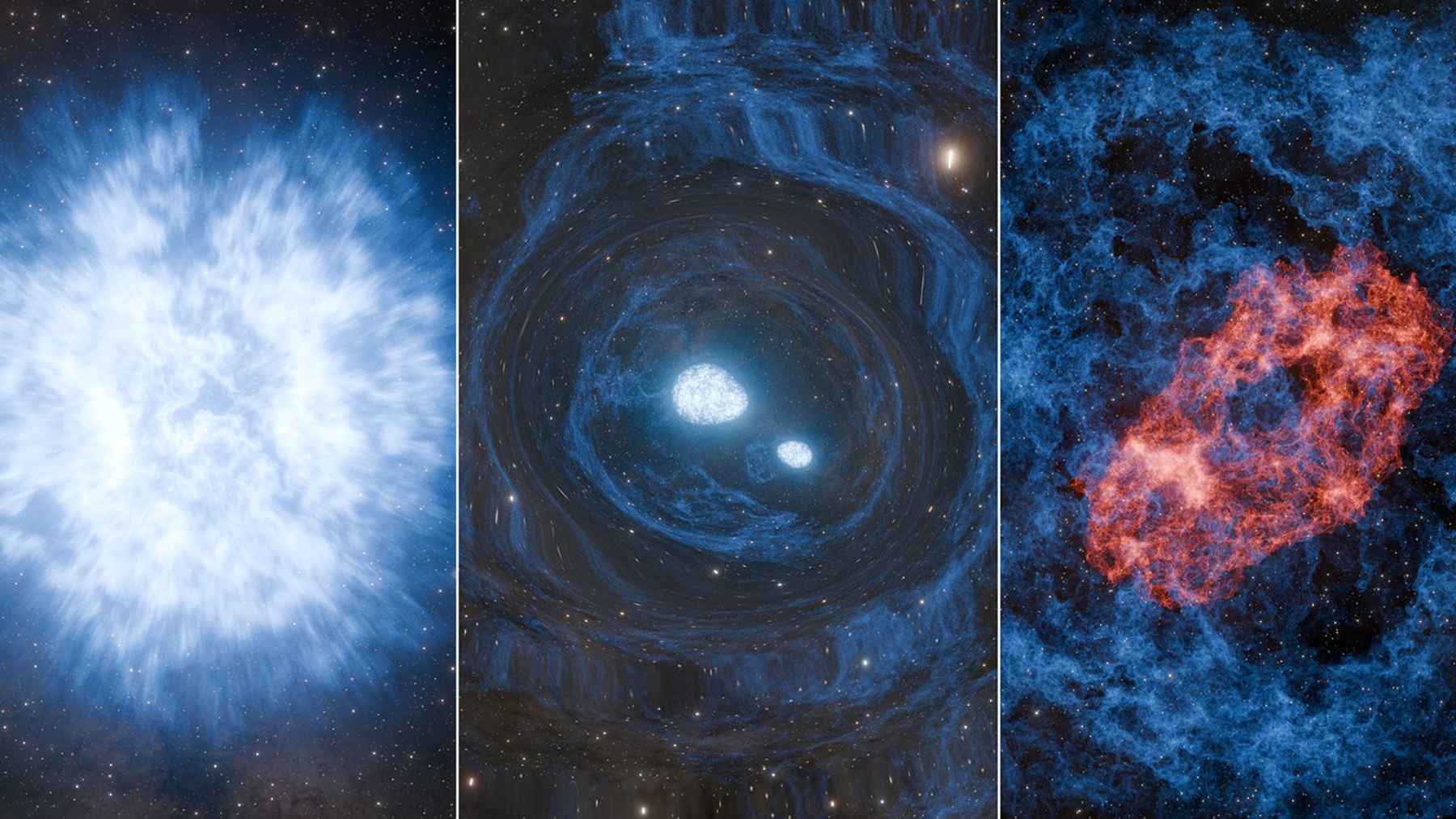

The star-shredding event that made the effect visible

The signal came from a tidal disruption event, when a star wanders too close to a supermassive black hole and gets pulled apart by uneven gravity. The debris can settle into a hot, flat disk of gas, and some material can be launched outward in narrow jets.

The outburst is known as AT2020afhd, in a galaxy called LEDA 145386 about 120 million light-years from Earth, first flagged in January 2024, according to a research update. Scientists then watched it for months, waiting for patterns that might reveal what the hidden black hole was doing.

The wobble that linked a disk and a jet

In the study, first author Yanan Wang and colleagues report that the disk and jets tipped back and forth together in a repeating cycle. The work was led by the National Astronomical Observatories of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (NAOC), with support from Cardiff University, and co-author Dr Cosimo Inserra highlighted the result in a press release.

Here is the key reason scientists take it seriously: the wobble showed up across different kinds of light. It was not just a small bump, either, but a sharp rise-and-fall that kept coming back on schedule.

Two telescopes, one repeating beat

To see that rhythm, the researchers combined data from the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, a NASA satellite that watches the sky in high-energy X-rays, and the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array, which picks up faint radio signals. The X-ray brightness rose and fell sharply, and the radio emission changed in step, creating a pattern that returned roughly every 20 days.

Why does it matter that the changes showed up in two kinds of light? Because it makes simple explanations, like random flickering, much harder to defend. When X-rays and radio waves move together, it strongly suggests the disk of gas and the jet are physically linked and wobbling as one system.

Why the finding matters beyond a theory test

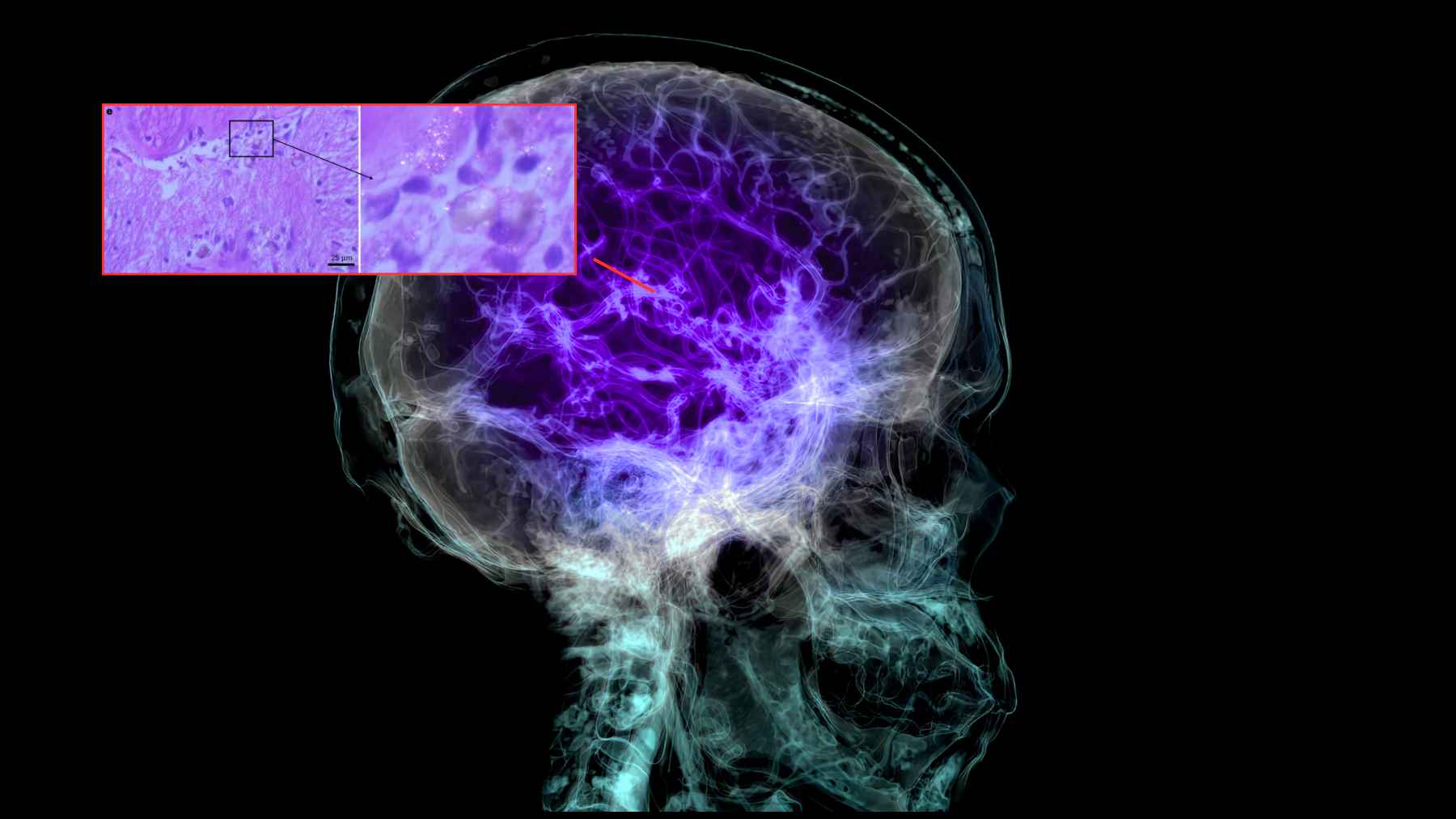

Black hole spin is hard to measure directly, and spin is thought to help shape jets and control how much energy they carry away. In practical terms, the wobble could become a new tool for estimating how a black hole is oriented and how fast it is rotating, using nearby matter as a tracer.

Frame-dragging has also been tested in Earth orbit, including by the Gravity Probe B mission. But a black hole is a far more extreme arena, and clear observations have been rare because tidal disruption events can fade or change before telescopes get enough data.

There have been hints during other star-disruption flares, like a 2024 report of repeating X-ray swings after a star was torn apart. What makes AT2020afhd different is the synchronized behavior across X-rays and radio, tying the wobble to both the disk and the jet, not just one band of light.

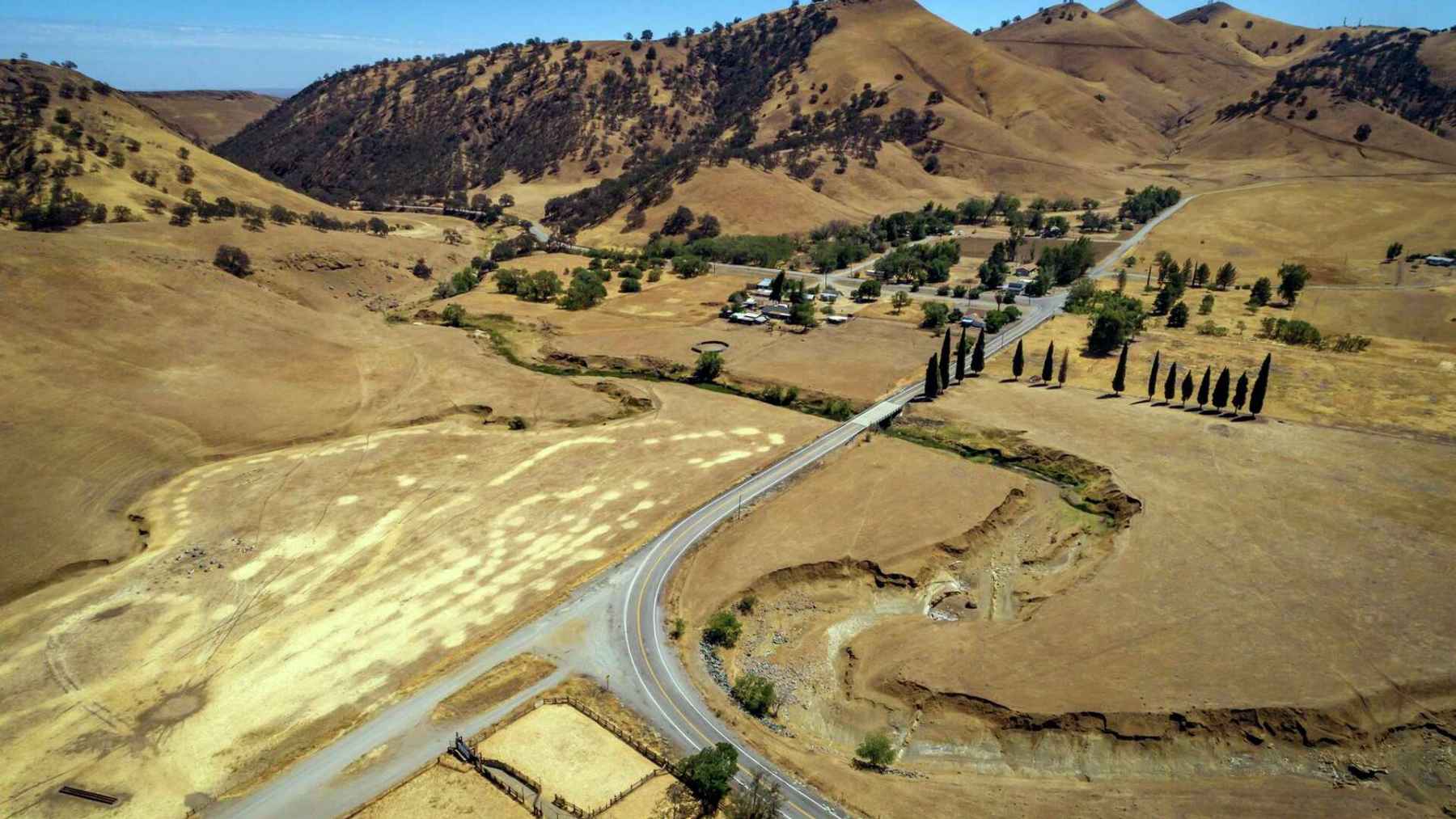

What comes next, and why timing is everything

This detection points to a simple lesson: cadence matters. If you only check in once in a while, a 20-day rhythm can vanish into the noise, like missing every other blink of a turn signal.

Future surveys and missions designed to spot sudden flares should make it easier to catch more of these events early and then monitor them often, including efforts like the Einstein Probe. The goal is not one rare example, but enough cases to learn when wobbling disks and jets are common, and when they are truly rare.

The main study has been published in Science Advances.