Canada has quietly set a new mark in the global race for fusion power. General Fusion says its latest compression experiments produced about 600 million fusion neutrons every second at peak, a record for its magnetized target fusion approach and a clear step toward controlled nuclear fusion.

In simple terms, the company has shown that it can squeeze a ball of super-hot gas hard enough and cleanly enough for fusion reactions to light up in a predictable way. The results come from the long-running Plasma Compression Science experiment series, whose data have been reviewed by independent scientists and published in the journal Nuclear Fusion.

A record that changes the fusion race

In fusion research, neutron output is one of the main scoreboards, since neutrons carry much of the reaction energy and prove that true fusion is happening. In these experiments, the team achieved a peak rate near 600 million fusion neutrons per second in a single compression shot, a figure that Canadian Nuclear Society leaders describe as a record for magnetized target fusion and an important validation of the concept.

Equally important is how the plasma behaved under stress. During compression, its density rose to about 190 times the starting value and the magnetic field that holds it in place grew more than 13 times stronger, while the plasma stayed stable instead of tearing itself apart and delivered repeatable bursts of fusion neutrons. Mike Donaldson, Senior Vice President for Technology Development at General Fusion, said the team has “demonstrated the viability of a stable fusion process” and laid the foundation for its LM26 project.

How magnetized target fusion works in simple terms

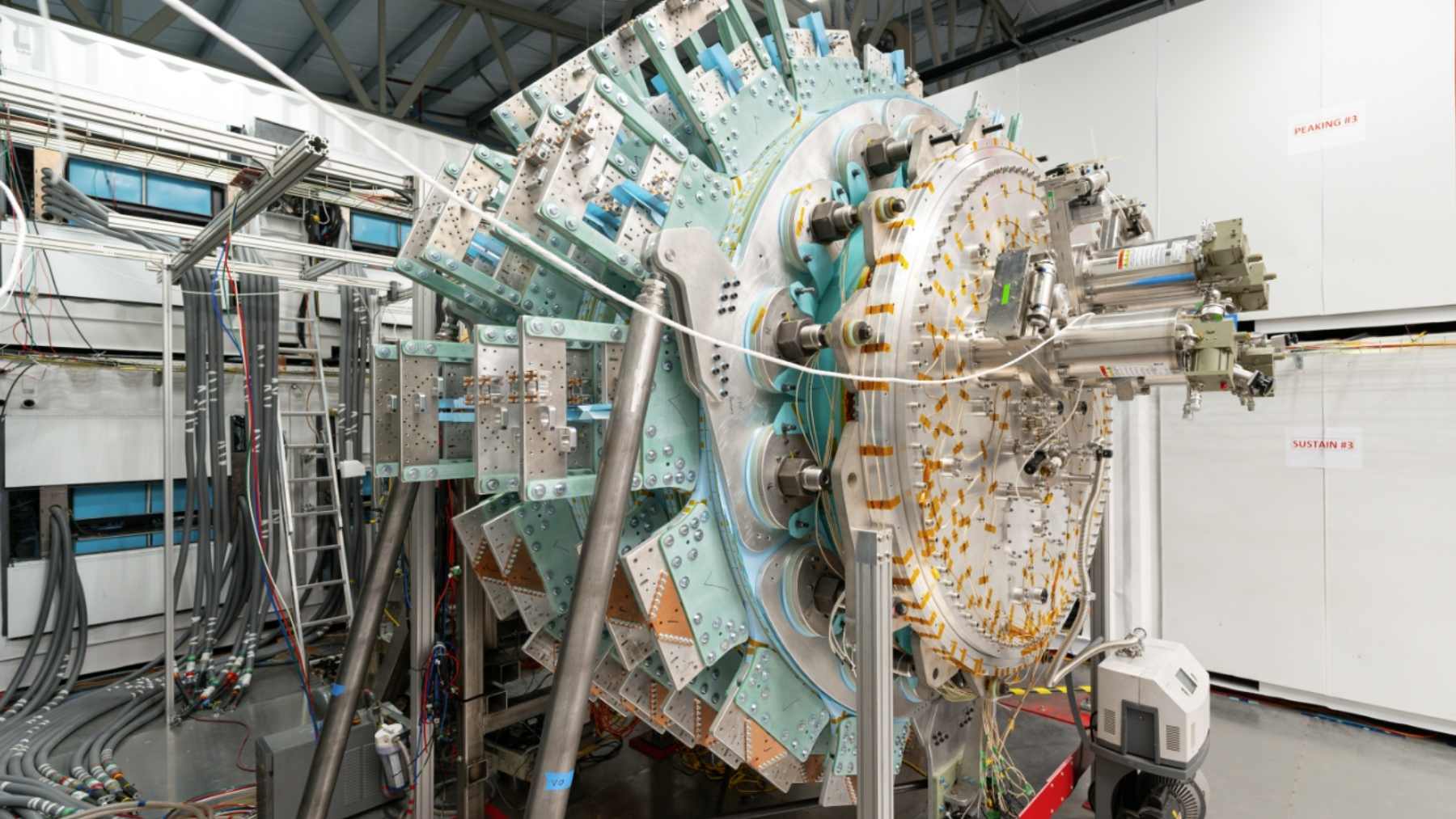

Magnetized target fusion starts with a magnetized plasma, which is a cloud of charged gas heated to millions of degrees, sitting inside a roughly spherical chamber. Around that chamber spins a layer of liquid metal and a ring of heavy pistons drive into the outer wall, forcing the metal to rush inward and squeeze the plasma at the center.

You can picture it a bit like pressing your hands into a water balloon from all sides at once, only here the fluid is metal and the center is as hot as a small piece of a star. Fusion happens when certain forms of hydrogen nuclei collide and stick together, releasing energy, and in this setup most of that energy comes out as fast neutrons that scientists can measure.

From lab experiments to the LM26 fusion machine

The Plasma Compression Science campaign was designed to answer one big question, whether a collapsing liquid metal liner can wrap around a spherical tokamak style plasma in a clean and symmetric way. Over years of shots, the experiment showed that this way of squeezing plasma is practical, repeatable, and able to reach the high densities and magnetic fields reported in the new results.

Those lessons now feed directly into Lawson Machine 26, or LM26, the larger demonstration device the company has built in Richmond, British Columbia. General Fusion describes LM26 as a magnetized target fusion machine intended to reach fusion conditions above one hundred million degrees and aim for scientific breakeven-style shots later this decade.

What happens next in the fusion race?

The next major milestone for General Fusion is to show that LM26 can repeatedly compress magnetized plasmas at conditions that look more like a real power plant. Company roadmaps outline a path from first plasma through higher temperatures to fusion-relevant shots that move closer to breakeven, and investors as well as governments will be watching whether the machine can hit those marks.

Even if LM26 meets every near-term target, fusion reactors will not appear overnight and specialists stress that big hurdles remain around net energy, reliability, and cost. At the end of the day, this burst of 600 million fusion neutrons per second is best seen as a sign that fusion research is moving from basic proofs toward the messy work of industrial engineering, the kind of progress that could one day influence electric bills.

The main study describing these compression experiments and their neutron yield has been published in the journal Nuclear Fusion.