The glittery mineral that once disappointed gold prospectors is getting a second look. New research suggests that iron pyrite, better known as fool’s gold, can hold surprising amounts of lithium inside certain shale rocks in the Appalachian basin. That finding hints at a fresh way to supply a key battery metal without cutting into new landscapes.

So what does fool’s gold have to do with your electric bill or the car charging in your driveway? Lithium-ion batteries sit at the heart of many phones, laptops, e-bikes and electric vehicles, and they also help store solar and wind power so the lights stay on after sunset. For the most part, that lithium still comes from big open pit mines or from brine ponds in very dry regions, and both routes can strain water supplies and damage habitats.

Fool’s gold and a very old shale

The new work comes from a team at West Virginia University that examined 15 sedimentary rock samples from the Appalachian basin in the United States. Inside these organic-rich shales, the researchers found plenty of lithium in pyrite grains tucked into the rock, something sedimentary geochemist Shailee Bhattacharya calls “unheard of.”

To test the idea, the team leached the rocks and tracked how much lithium came out of different mineral fractions. In some samples with relatively low overall lithium levels, as much as 54 percent of the total lithium appeared in the pyrite fraction. The more pyrite there was, the more lithium tended to show up in the leachate.

That suggests pyrite is not just an innocent bystander inside the rock. It may act as a host for lithium and as a handy clue when geologists go looking for new lithium-rich shales. Fool’s gold could become a marker mineral for a metal that sits inside your pocket every time you pick up your phone.

Mining value from past mining

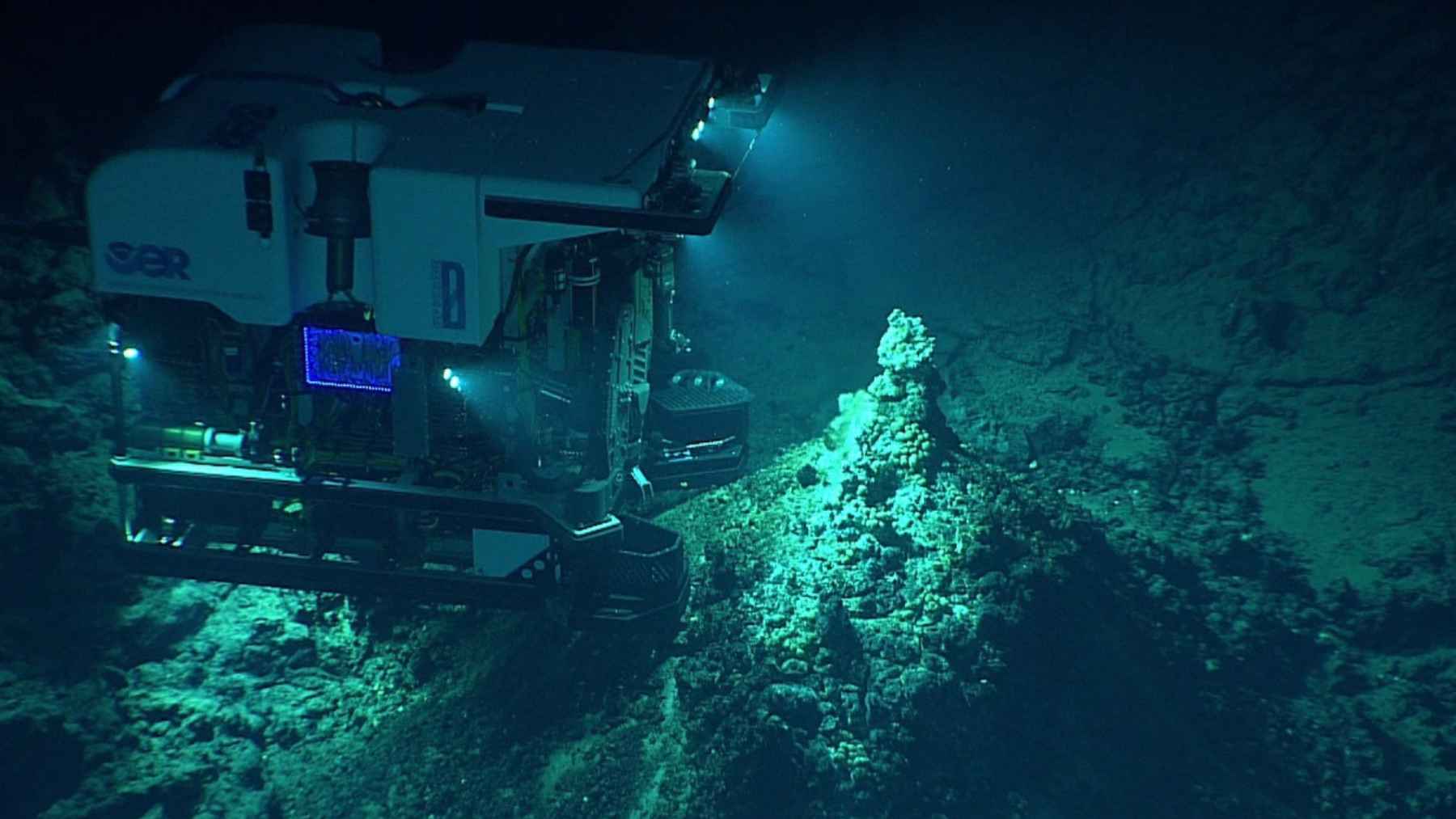

The team focused on material connected to existing industrial activity, such as drill cuttings and mine tailings, so the pyrite rich shale was already disturbed by earlier operations. Bhattacharya notes that this is a “well-specific study” and stresses that more research is needed before anyone can say whether the approach will work at scale or make economic sense.

Even so, the idea points in a direction many sustainability experts would like to see. Instead of pushing into new wilderness for every ton of lithium, operators could one day co-produce some of it from waste piles and leftover rock that already sit on the surface. That kind of co-production would not erase the impacts of fossil fuel extraction or hard rock mining, but it could nudge existing sites closer to a circular economy.

Why this matters for the batteries of the future

Engineers are already testing lithium sulfur batteries as an alternative to some conventional lithium ion designs. Sulfur is common and relatively easy to source, so pairing it with lithium could shrink the material footprint of future batteries. If some of that lithium can be recovered from pyrite-rich shales that are already part of industrial sites, the total pressure on fragile ecosystems may drop a bit.

Experts are careful not to oversell the discovery. The samples come from a single basin, and the curious partnership between lithium and pyrite may not show up in the same way elsewhere. The lithium concentrations are modest compared with dedicated ore deposits, and no one has yet proven a full scale extraction process in the field.

Still, the work widens the map of where critical minerals might hide. It shows that a mineral long treated as a joke by prospectors can carry a different kind of value in a low-carbon economy. As demand for batteries keeps climbing and communities push back against the heaviest impacts of mining, ideas like lithium in fool’s gold hint at a future where we get more of what we need from places we have already disturbed.

Pyrite will keep showing up as glittery cubes in rock shops and on classroom shelves. Quietly, though, it may also be teaching geologists how to see old mine waste and drill cuttings with new eyes.

The study was presented at the EGU General Assembly and published on the EGUsphere site.