Researchers at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory are developing a new, commercially-feasible solar cell that is capable of harnessing the entire spectrum of solar radiation including low-energy infrared and high-energy ultraviolet.

The Solar Energy Materials Research Group in the Materials Sciences Division at the laboratory recently demonstrated the new solar cell, made using one of the most common manufacturing processes available in the semiconductor industry.

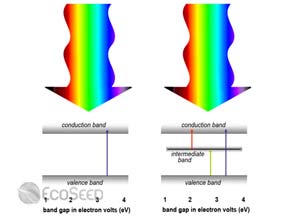

“The underlying principle of a successful full-spectrum solar cell is to combine different semiconductors with different energy gaps,” explained Wladek Walukiewicz, the group’s lead researcher.

Initially, the group combined these different energy gaps by piling layers of different semiconductor alloys atop each other and wiring these in series.

They stacked crystalline layers with varying but closely-matched indium content to create a photovoltaic device that is sensitive to the full solar spectrum.

But the researchers concluded that this structure is still too complex, and complicated to manufacture, even if the layers are well- matched. To simplify the structure, they made an alloy of highly mismatched semiconductors from a zinc and tellurium.

The researchers infused oxygen as a doping agent to add a third distinct energy band between the two. This created three different band gaps that cover the solar spectrum.

But producing this alloy was still complicated and time-consuming. Additionally, these solar cells are costly to produce in quantity, said Mr. Walukiewicz.

Finding the right material

“The major issue in creating a full-spectrum solar cell is finding the right material,” noted Kin Man Yu, a member of the research group.

“The challenge is to balance the proper composition with the proper doping,” he added.

The latest solar cell is a multi-band semiconductor composed of highly mismatched gallium arsenide nitride alloy. The alloy is similar in composition to gallium arsenide, one of the most common semiconductors available today.

The scientists replaced some of the alloy’s arsenic atoms with nitrogen to create a third intermediate energy band which will allow it to be sensitive the whole solar spectrum.

Furthermore, the alloy can be made through metalorganic chemical vapor deposition. This is a common semiconductor production process where thin layers of atoms are deposited into a semiconductor wafer.

Full spectrum testing

The researchers used the new multi-band alloy as the core of a test solar cell to determine how much current is produced by different colors of light.

According to Mr. Walukiewicz, the intermediate band must absorb light without conducting an electric charge to prevent the device from short-circuiting. Results of the tests conclude that the new alloy responded strongly to all parts of the light spectrum, from infrared to ultraviolet.