Danish sustainable energy research institution Risø DTU is working on air-fueled batteries that could be the power source of the next generation of emission-free electric vehicles.

“If we succeed in developing this technology, we are facing the ultimate break-through for electric cars, because in practice, the energy density of Li-air batteries will be comparable to that of petrol and diesel, if you take into account that a combustion energy only has an efficiency of around 30 percent,” said Tejs Vegge, a senior scientist at Risø DTU’s Materials Research Division.

A lithium-air battery or Li-air battery is designed with a lithium electrode as the anode and a porous carbon electrode as its cathode. The cathode lets in and attracts air and during discharge, the lithium and oxygen react to form lithium peroxide and a charge that drives the battery.

The lithium-air battery is similar to the lithium-ion battery but has a greater energy density. One of the problems with current lithium-ion battery packs is their cost and the relatively low amount of energy they can store.

The energy density of today’s batteries is said to be almost two orders lower than that of fossil fuels. This means that a battery pack containing energy corresponding to 50 liters of fuel would need to weigh between 1.5 and 2 tons.

In order to get more use from lithium-based batteries – especially in the field of personal electronics and vehicles – they must be made lighter and smaller but still able to produce a lot of energy.

Because of their high energy density, Li-air batteries are particularly promising in this front. However, they are not without their share of challenges that need to be overcome before commercialization.

While current Li-air batteries start off lighter than Li-ion batteries, the fact that they absorb oxygen atoms means that they gain weight as they are being used. Also, the lithium peroxide formed by the battery’s reactions can cause the batteries channels to be blocked and prevent the flow of additional oxygen.

While Li-air batteries are rechargeable, they need an extremely high overvoltage to recharge. The equilibrium voltage for the battery is 3 volts, dropping to 2.6-2.7 volts when it is discharging. To recharge, the voltage must be increased to 4.5 volts.

“The high overvoltage for recharging is hard going for the current battery components, which limits the number of times the battery can be recharged,” says Poul Norby, senior scientist of the Materials Research Division.

The cyclic energy loss in charging/recharging is about 40 per cent in Li-air batteries. The challenge is to reduce this number to 10 per cent, corresponding to Li-ion batteries.

The researchers are currently using extensive computer calculations to observe how lithium and oxygen atoms interact in order to find an explanation of the high overvoltage and a solution.

Li-air batteries also can currently handle only 50 charges and the researchers need to increase that amount to around 300 charging and discharging cycles for it to be practical for electric vehicle use.

“This is the true challenge for the Li-air batteries, because they may potentially be able to contain the same amount of energy as petrol, but it takes considerably longer to refuel,” said Mr. Vegge.

Improving the Li-air battery technology is part of the focus of two divisions within Risø DTU, the Materials Research Division and the Fuel Cells and Solid State Chemistry Division.

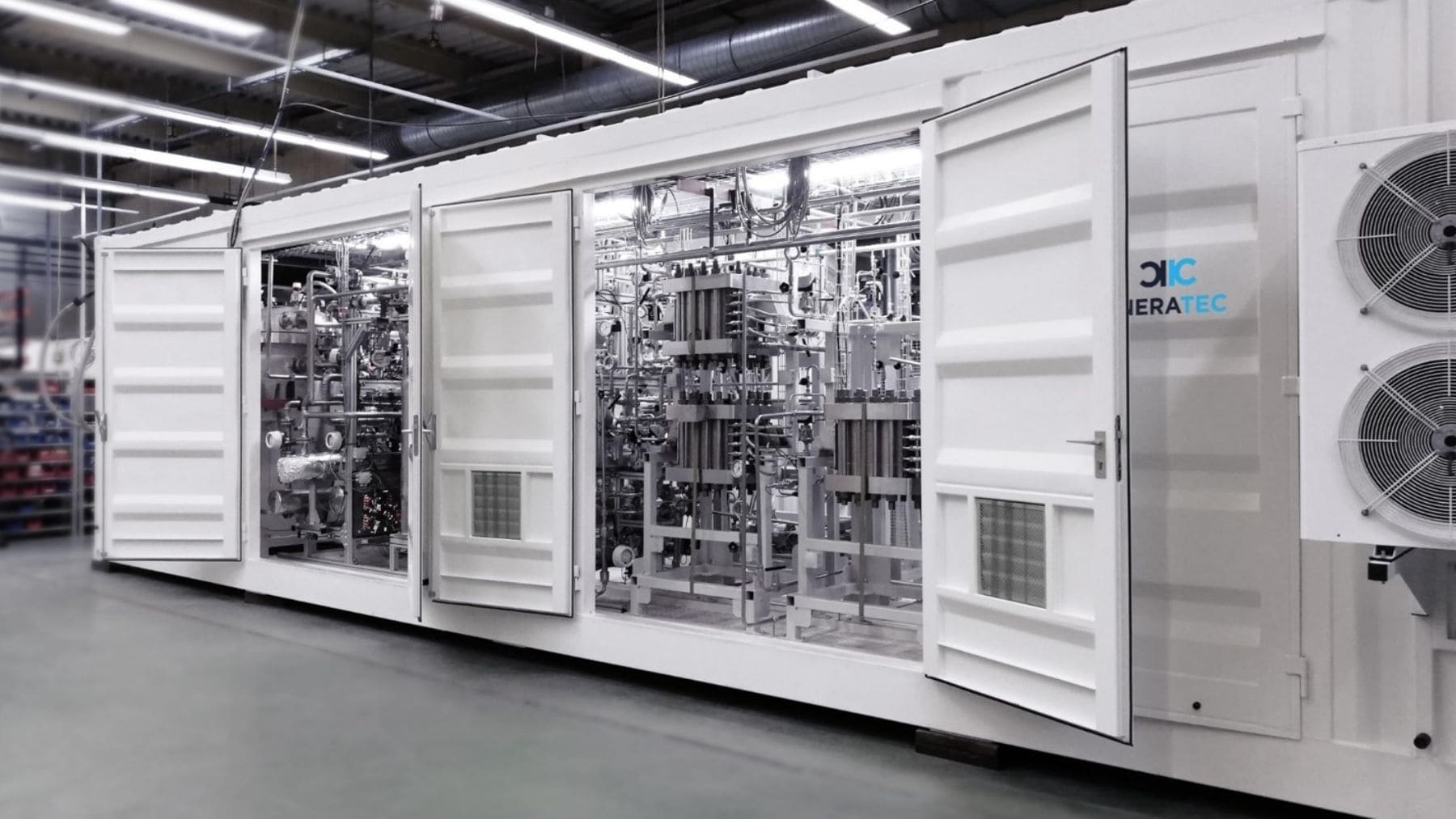

The Fuel Cells and Solid State Chemistry Division is also working on the area of energy storage for renewable energy generation.

The researchers are trying to develop a distributed energy system to store surplus renewable energy as chemical energy in the form of compounds such as liquid methanol or gases.

The goal is to transform excess electricity to chemical energy via an electrolytic process that happens in an electrolytic cell. Electrolysis transforms water into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity.